In 1993, Keith Scott was released on parole from a Pennsylvania state prison. A decade earlier, he’d pled guilty to a charge third-degree murder ten years earlier and was sentenced to between 10 and 20 years in prison. The terms of Scott’s parole agreement stated that he could not own a firearm, drink alcohol, or engage in “assaultive behavior.” Scott also consented to let parole officers search his residence without a warrant—and, if they found any evidence of a parole violation, to admit that evidence in a parole revocation hearing that could send him back to prison.

Five months later, officers indeed searched Scott’s residence, which at the time was his mother’s house, after arresting him on suspicion of several parole violations. The officers did not ask Scott’s mother for consent to search her house. She did not give consent for the search, and Scott’s mother didn’t try to stop it, either—a not-unreasonable decision for any person approached by multiple armed law enforcement officers.

Inside, they found several guns, which became evidence against Scott at a subsequent parole revocation hearing. Scott moved to suppress the evidence, arguing that warrantless search violated his Fourth Amendment right to be free of “unreasonable searches and seizures.” In Mapp v. Ohio, decided in 1961, the Supreme Court had held that when a police officer illegally obtains evidence against a defendant, that evidence cannot be used against them at trial—a concept known as the “exclusionary rule.”

A Pennsylvania state court agreed with Scott, finding that the exclusionary rule should apply to the guns. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court affirmed, reasoning that Scott couldn’t waive his Fourth Amendment rights within the language of a parole agreement, and that the officers conducted the search without the requisite “reasonable suspicion” that Scott had violated the terms of his parole. Without the exclusionary rule, the court concluded, parole officers would be undeterred from gathering evidence against parolees for parole hearings through illegal searches.

The state parole board appealed, though, and 25 years ago this month, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that Keith Scott was out of luck. In Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole v. Scott, a five-justice majority decided that the exclusionary rule does not apply to evidence in parole revocation hearings. In his opinion for the majority, Justice Clarence Thomas gave law enforcement officials broad discretion to define what fundamental rights a person on parole or probation has once they set foot outside the prison’s walls. In doing so, Thomas continued 62 years of conservative Supreme Court reaction to Mapp, depicting the exclusionary rule as a misguided form of judicial activism that puts public safety at risk.

When someone asks if you think the Fourth Amendment is “important” (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

First, Thomas writes that the exclusionary rule applies “only where its deterrence benefits outweigh its ‘substantial social costs.’” This language comes from a previous Supreme Court case, United States v. Leon, in which the Court invented a “good faith exception” to the exclusionary rule—when police obtain evidence based on a defective warrant they believed was proper, the Court ruled, the exclusionary rule doesn’t apply. In Leon, Justice Byron White warned that the result of “indiscriminate application” of the exclusionary rule is that “some guilty defendants may go free or receive reduced sentences as a result of favorable plea bargains.” Thomas used the same logic to carve out an exception here, too.

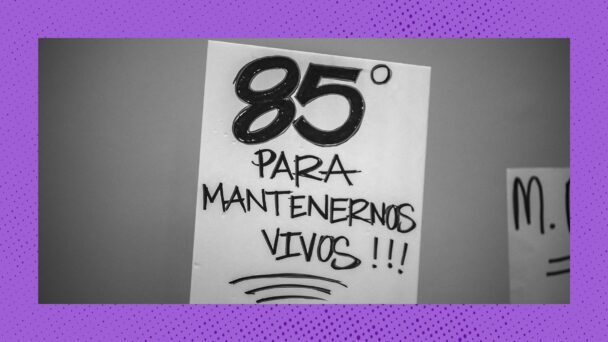

There are two main problems with Thomas’s (and White’s) analysis. First, of the thousands of criminal defendants that challenge evidence under the exclusionary rule each year, a substantially smaller percentage of those defendants are successful. One oft-cited study that looked at 7,500 cases in three states found that over 85% of defendants who successfully excluded evidence were facing minor drug possession charges, and only one faced over a year in prison. Based on this information, it is hard to claim that the social cost for the exclusionary rule is public safety.

Second, this “social cost” is not a flaw of the exclusionary rule. It is the reason the rule exists. The Supreme Court made this clear in Mapp, saying, “The criminal goes free, if he must, but it is the law that sets him free. Nothing can destroy a government more quickly than its failure to observe its own laws, or worse, its disregard of the charter of its own existence.” The exclusionary rule is the only incentive police have to comply with the warrant requirement. White’s focus on creeping “substantial social costs” is a blank check that Supreme Court can fall back on each time the justices decide to weaken the rule.

(Photo by Al Drago/Getty Images)

In Scott, Thomas also claims that parole hearings are designed to be “predictive and discretionary.” Here, Thomas cites Gagnon v. Scarpelli, in which the Court ruled that parolees do not have a right to an attorney during “quasi-judicial” parole hearings, since the very presence of lawyers might cause parole boards to “be less tolerant of marginal deviant behavior and feel more pressure to reincarcerate than to continue nonpunitive rehabilitation.” Thomas warns that the exclusionary rule would transform parole revocation hearings from “flexible, administrative procedures” into “trial-like” situations that are “less attuned to the interests of the parolee.”

Thomas does not explain how the “predictive” and “discretionary” aspects of Keith Scott’s parole hearing benefited him, or why it was not in Scott’s best interest to have access to the exclusionary rule when parole officers used illegally obtained evidence to send him to prison. The Court entirely ignores the possibility that parole boards might feel less comfortable reincarcerating a parolee with legal representation in the room. Few parolees would be able to confidently argue for the suppression of evidence at a parole revocation hearing without the assistance of a lawyer.

Thomas goes on to make a two-part claim that displays a profound misunderstanding of police and parole officer incentive structures. First, he acknowledges that a regular police officer may be gathering evidence against a parolee prior to a parole revocation hearing. To Thomas, the parolee is in luck, because that officer is necessarily operating with the exclusionary rule in mind. “The remote possibility that the subject is a parolee and that the evidence may be admitted at a parole revocation proceeding surely has little, if any, effect on the officer’s incentives,” he wrote.

In reality, as Justice David Souter noted in dissent, police are fully capable of knowing if a person is on parole before they gather evidence. (“The local police know the local felons,” Souter said.) Pennsylvania’s parole procedures actually require parole officers to inform police about where a parolee will be living, and to cooperate with investigations that implicate the parolee. Thanks to Thomas’s opinion, if a police officer is looking for evidence against a parolee, they now have two options: Abide by the Fourth Amendment and lawfully gather evidence against the parolee for a new crime, or ignore the Fourth Amendment and hand that evidence to a parole board conducting a parole revocation hearing, where the exclusionary rule doesn’t apply. For police officers, guess which option is more appealing!

Maybe the silliest part of Thomas’s argument is that parole officers are too invested in the parolee’s success to violate their rights. The relationship between parole officer and parolee, he says, is “more supervisory than adversarial,” and that it is thus “unfair to assume that the parole officer bears hostility against the parolee that destroys his neutrality.” A parolee who returns to prison, Thomas continues, “is in a sense a failure for his supervising officer.”

In the context of Scott, this characterization is especially ridiculous. This case, after all, is about an actual situation in which parole officers violated Scott’s Fourth Amendment rights. More than half of Pennsylvania parolees who have their parole revoked are sent back to prison for a technical violation like missing a meeting with a parole officer or violating curfew. If parole revocation is a professional scarlet letter for parole officers, that’s a lot of shame to go around.

Today, about 4.5 million people are on some form of court-ordered supervision, living with diminished rights thanks to Supreme Court decisions like Scott. And conservatives continue to look for ways to grind the exclusionary rule away to basically nothing: In a concurrence to a 2018 case, Collins v. Virginia, Thomas expressed skepticism about the exclusionary rule’s application to states—a change to the status quo that would functionally abolish the rule. “We have not yet revisited that question in light of our modern precedents, which reject Mapp’s essential premise that the exclusionary rule is required by the Constitution,” he wrote. “We should do so.”

Thomas wrote only for himself in Collins. But that was five years ago. Today, previously-fringe positions about longstanding Supreme Court precedents are gaining traction among members of the Court’s empowered conservative wing, which can afford to lose one justice and still have five votes. When judges chip away at fundamental rights in the name of “safety,” they are setting the stage to eliminate those rights entirely.