The Supreme Court fundamentally changed the nature of the presidency last week. On July 1, the Court issued its long-awaited decision in Trump v. United States and ruled 6-3, along party lines, that presidents are entitled to absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for “official acts” that are within their “exclusive sphere of constitutional authority,” as well as “presumptive immunity” for other official acts. The Court’s Republicans did not see fit to say what “official acts” actually are, saying only that “that analysis ultimately is best left to the lower courts to perform in the first instance.” As a result, Americans are now basically in a slow-moving horror movie, and to find out what presidential actions do and don’t warrant immunity, the Court has told us to wait for the sequel—Coup 2 Electric Boogaloo.

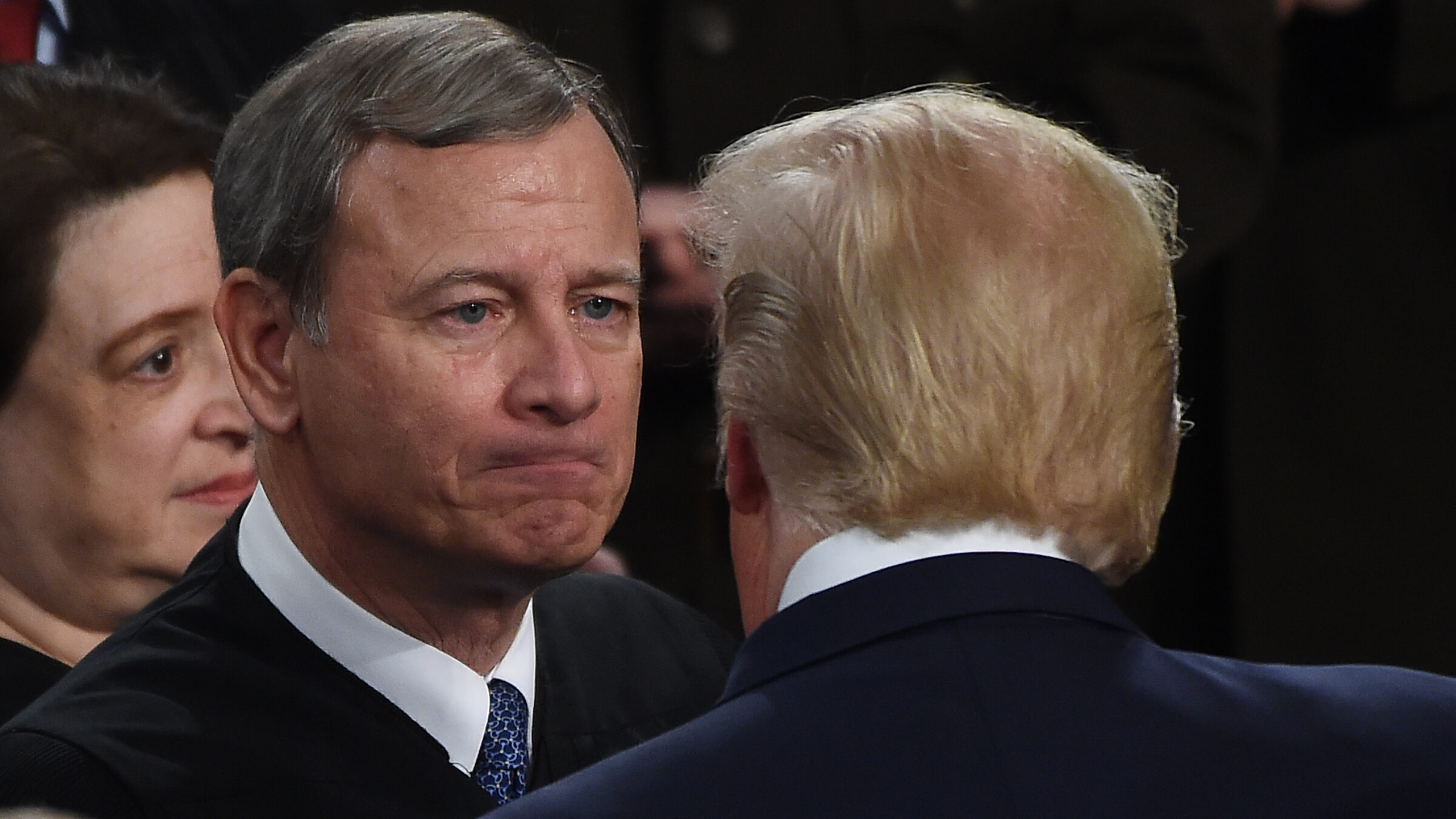

In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts justified this outcome by arguing that “the nature of presidential power” and “our constitutional structure of separated powers” require it: A president might hesitate to “execute the duties of his office fearlessly and fairly,” Roberts warned, if he were worried about prosecution.

Of the many things I worry about Trump doing, “hesitating” is not one of them. The former president was already unafraid to instigate a deadly attack on a co-equal branch of government in an effort to overturn a democratic election. It would be good, actually, if someone had given him a reason to stop and think, Maybe I shouldn’t do that. Instead, Roberts handed Trump a permission slip to try harder next time, while making vague gestures about safeguarding “the independence and effective functioning of the executive branch.”

But Roberts’ proffered legal justification is almost beside the point. This case had virtually nothing to do with law, and everything to do with power. Both the decision in the immunity case and the process by which the Supreme Court made its decision were deliberately crafted by a Republican supermajority to maximize the electoral chances of the Republican nominee.

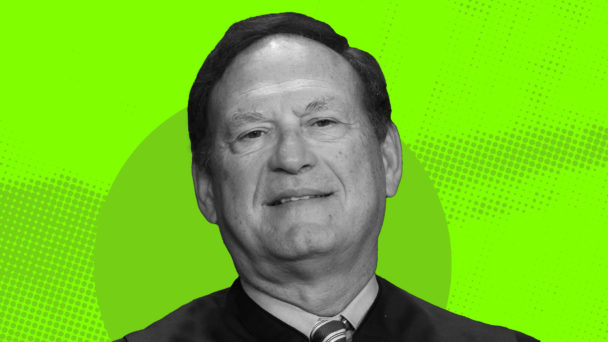

The idea that presidents cannot be prosecuted for crimes is nowhere to be found in the text of the Constitution, and has no basis in any of the interpretive theories the Court typically claims to care about. In dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor described the majority’s position as irreconcilable with text and history: “Settled understandings of the Constitution are of little use to the majority in this case, and so it ignores them,” she writes. “History matters to this Court only when it is convenient.”

The Court also didn’t need to take up this case in the first place. Back in February, the D.C. Circuit issued a unanimous decision rejecting Trump’s immunity claims. When Trump petitioned the Supreme Court to review the case, the Court could have simply said no and allowed the decision to stand. Alternatively, the Court could have easily disposed of this case by summarily affirming the D.C. Circuit. It had options! The only reason to pick this option and even entertain the argument that Trump is a god-king is to help him run out the clock until the November election, at which point Trump could retake power and put an end to his own prosecution. By using the last day of the Court’s term to invent a broad sphere of presidential immunity, Roberts and company pushed the possibility of Trump experiencing consequences for his attempt to overturn the 2020 election firmly out of reach.

(Photo by OLIVIER DOULIERY/AFP via Getty Images)

It was not a foregone conclusion that there would be no time to bring Trump to trial. The Court is perfectly capable of moving quickly when it wants to. The Court ruled on United States v. Nixon only 16 days after oral argument; it decided Bush v. Gore a single day after oral argument; and it took only 25 days after oral argument in Trump v. Anderson for the Court to force states to keep Trump on the 2024 ballot. There is a simple explanation for why a Court controlled by six Republicans took so long to decide the political future of a Republican presidential nominee: It benefited their ideological ally.

Perhaps the most ominous aspect of the Court’s ruling is that Trump is not the only aspiring autocrat who will relish it. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s dissent emphasizes that the threat of legal accountability for committing criminal acts is a deterrent against “future presidents who might otherwise abuse their power,” and that the Court’s preemptive release of the law’s constraints “reduces incentives to follow the law” at all. And, to make matters worse, the Court’s refusal to say what falls within these new categories of official and non-official acts means there are no clear boundaries on illegal acts. The only nominal backstop is the corrupt Court itself.

The Supreme Court’s attempts to clothe this decision in law are utterly unavailing. It is a nakedly partisan gift to the Republican presidential nominee. And by bending over backwards to protect Trump, the Court bent over backwards for future aspiring authoritarians, too.