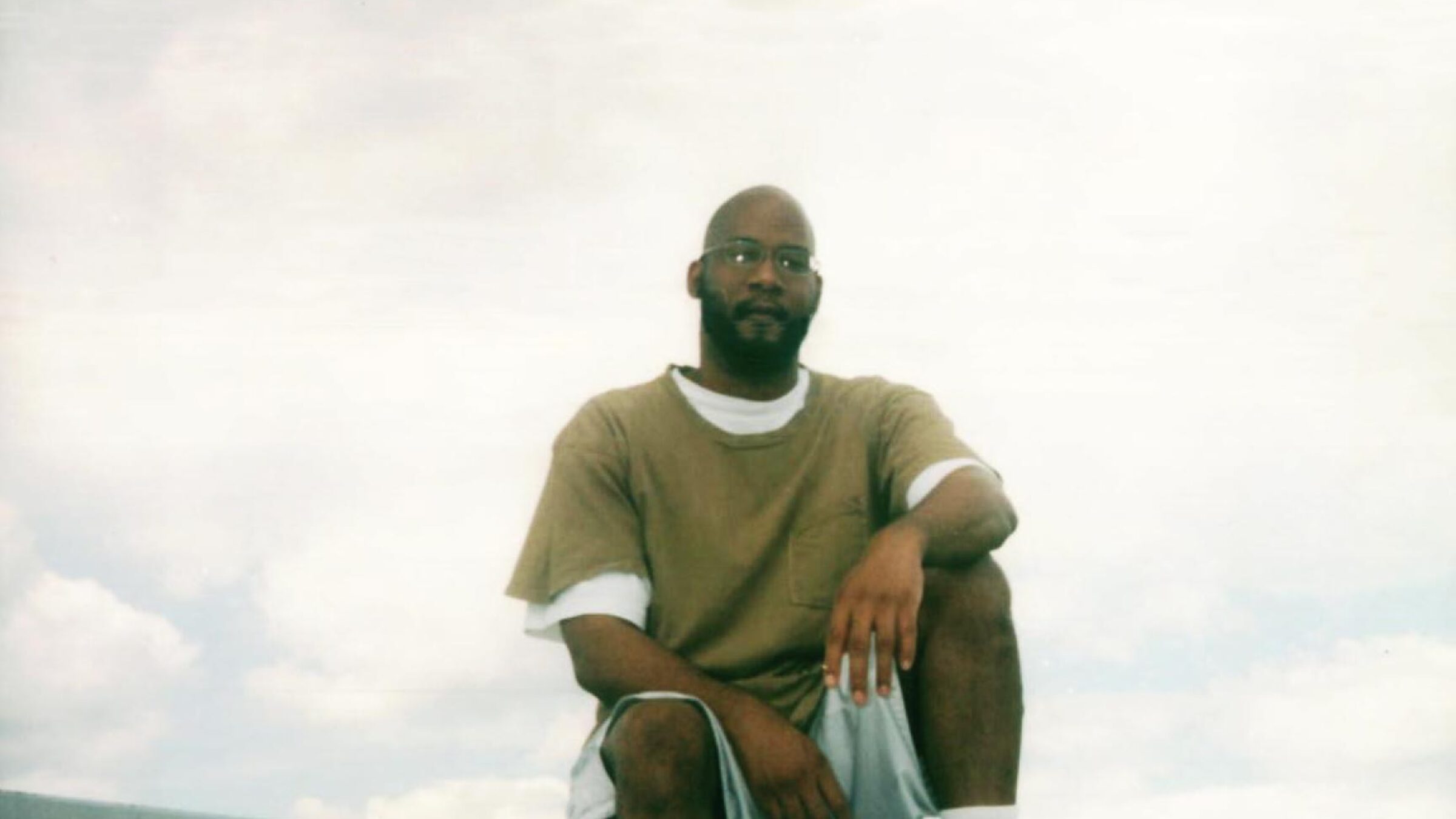

Last week, the state of Missouri executed Marcellus Williams for the 1998 murder of Felicia Gayle, a St. Louis journalist. No physical evidence connected Williams to the crime of which he was convicted, and the testimony against him at trial—given by his then-girlfriend Laura Asaro and jailhouse informant Henry Cole, both of whom were keenly interested in the available reward money, and both of whom police pressured to cooperate—was inconsistent with the findings at the scene. The bloody shoe prints in Gayle’s home were not made by Williams’s shoes; the fingerprints on the wall were not Williams’s fingerprints; the hair on the floor was not Williams’s hair. Three experts who independently reviewed DNA test results of the knife used to kill Gayle concluded that Williams had not been the one who wielded it.

This ignored evidence of actual innocence was not the only way in which the criminal legal system failed Williams. During jury selection, the prosecutor struck six of seven Black prospective jurors, yielding a jury of 11 white members and one Black member. (Under oath, the prosecutor remembered striking a juror who, like Williams, was a young Black man who wore glasses, on the grounds that he thought they looked like “brothers.”) At trial, Williams’s lawyers failed to challenge Asaro’s and Cole’s testimony; at sentencing, they did little to introduce mitigating evidence about Williams’s background that might have prompted jurors to spare his life. In the years since, prosecutors in St. Louis fought to vacate the conviction that their own office obtained, noting that police officers, in an especially cruel turn of events, had spoiled evidence at the crime scene that might have definitively exonerated him.

None of this mattered to the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, who on Tuesday issued an unsigned order denying Williams’s request for a stay of execution. Only the three liberals—Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson—noted their dissent, which they, too, did not explain any further. The American legal system’s response to Williams’s last appeal for his life thus appears below in its entirety.

This convention is very much the norm for the Supreme Court’s death penalty docket. (As Chris Geidner notes at Law Dork, the order is just one of three, all of which appear in the same format, that the Supreme Court issued that same afternoon to deny Williams’s requests for relief.) In the occasional death penalty case, the justices who would grant a stay of execution write full dissenting opinions explaining their votes. But those in the majority rarely bother showing their work, which means that nearly every time a person condemned to death asks the Supreme Court to intervene, the justices who deny that request do so in fewer words than it would take to place their group coffee order.

The brevity of these death sentences stems in part from their presence on the Court’s shadow docket, which the justices use to resolve matters that come before them on an “emergency” basis. As Steve Vladeck explains in his 2023 book The Shadow Docket, since the Court ended its brief ban on capital punishment in 1976, the justices have responded to the corresponding expansion of their death penalty docket by providing far less process in such cases than they did previously, when they frequently held in-chambers oral argument and explained their decisions in writing. Between 1980 and 2022, states executed some 1500 people. During that 42-year period, the Court deigned to hear oral argument on emergency applications for relief exactly zero times.

In recent years, the conservative justices have pushed even harder to greenlight executions more expeditiously, spurred on by their fondness for capital punishment, their indifference to the racism that permeates its administration, their inherent skepticism of legal claims brought by convicted criminals, their eagerness to punish people branded as undeserving of mercy, and their desire to achieve vengeance and finality over justice and fairness. No statute requires the justices to do more work than they feel like doing, and the Court jealously guards its power to decide how to conduct itself without interference from or oversight by the other branches of government. The result is a status quo in which the justices treat requests for stays of execution as annoying inconveniences, and are content to dispose of the people before them by opening a WordPerfect template, changing the names, hitting print, and walking out of the office.

Images courtesy the Innocence Project

In a country that aspires to fulfill the promise of equal justice under law, there would be no place for the death penalty, a barbaric anachronism that does nothing to keep people safe. For as long as it persists, however, the legal system owes more to the people whose lives it has the power to take. The extremely powerful and otherwise unaccountable lawyers at the very top of this system should not be able to order deaths in bloodless, two-paragraph orders, hiding behind the majesty of their offices, as comfortably removed as ever from the real-world consequences of their actions. They should bear the burden of providing a full accounting of these decisions, and feel shame when confronted by the reality that they are unable to do so. They should have to justify in painstaking detail their conclusion that, in light of all the relevant facts and circumstances, the even-handed administration of the law is possible only through more state-sanctioned killing.

And at the very least, the justices should have to sign their names to what they are doing. As he wound his way through a system that slammed door after door in his face, Marcellus Williams deserved to know who had the final say in deeming his life unworthy of their time and attention. So do the rest of us, in whose names the government will keep killing people like Marcellus Williams for as long as it can get away with it.