On Election Day 2024, Justice Allison Riggs, a Democrat, won re-election to a full eight-year term on the North Carolina Supreme Court. Her Republican opponent, Jefferson Griffin, is now asking the court’s supermajority of Republican justices to steal it.

Riggs’s initial margin of victory was sufficiently narrow that Griffin, a state appeals court judge, sought and obtained two recounts, as state law allows in close races. But the result did not change: On December 10, after all the votes had been tabulated (and then retabulated and retabulated), the elections board confirmed that Riggs prevailed by 734 votes.

In a functioning democracy, the story would end here: The board would certify the results, Griffin would concede, and Riggs could get back to reading her stack of briefs. Unfortunately, we are talking about North Carolina, a state where Republicans control the state supreme court by (for now) a 5-2 margin, and where savvy Republican politicians have spent decades perfecting the art of abusing their offices to entrench themselves in power. Sure enough, in December, Griffin sued to overturn the results, asking the North Carolina Supreme Court—yes, the same court he seeks to join—to throw out some 60,000 mail-in ballots on various, spurious grounds.

Before officials began counting mail-in ballots, Griffin had an edge of about 10,000 votes. If the court’s Republican majority were to grant his request, they would almost certainly flip Riggs’s seat to a Republican pickup.

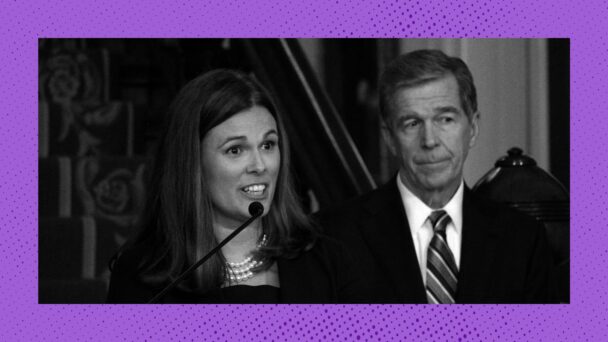

Riggs speaks to reporters after her appointment to the state supreme court by Gov. Roy Cooper, September 2023 (AP Photo/Hannah Schoenbaum)

Recognizing both the serious implications for voting rights and also the screaming conflict of interest, the state board of elections sought to move the case to federal district court. But on Monday, Judge E. Richard Myers II, a Trump appointee, granted Griffin’s request to return the matter to the state supreme court, citing his deep respect for “state sovereignty” and “the independence of states to decide matters of substantial public concern.”

The board has appealed Myers’s decision to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. But in the meantime, the Republican justices needed only a day to issue an order blocking the board from certifying the results until they resolve Griffin’s case. What this means is that soon, a supermajority of North Carolina Republicans will decide whether to re-seat their Democratic colleague who just won an election, or to retroactively disenfranchise tens of thousands of people in the hopes that for Griffin, the third recount will be the charm.

Riggs has understandably recused herself, leaving the only other Democratic justice, Anita Earls, to dissent from the order, criticizing the court’s “indulgence of…fact-free post-election gamesmanship.” Justice Richard Dietz, a Republican, wrote a more muted dissent, warning that candidates’ attempts to rewrite election rules fuel “an already troubling decline in public faith in our elections.” The four other Republicans, perhaps too enamored by the possibility of expanding their supermajority to six, were unpersuaded by either argument.

Griffin’s case is, to use a term of art, dogshit. His principal argument is that the court must invalidate ballots cast by people whose registration forms did not include a correct driver license or Social Security number. But many North Carolina voters registered long before the state collected this information, and the state’s voter registration form, which officials are constantly tweaking to comply with changes in election laws, didn’t even make this technical requirement clear until about a year ago. Everyone with a purportedly insufficient registration who cast a ballot in 2024 would also have had to comply with North Carolina’s voter ID law, which Republicans passed six years ago. There is no serious question about the identity of these voters, their eligibility to vote, or the integrity of the election result.

You do not need to take my word for it here: Griffin’s argument is so weak that, in a strategy call convened in July, a prominent conservative activist in North Carolina dismissed the idea of challenging registrations with missing driver license or Social Security numbers as “voter suppression” that was “100 percent sure” to fail in court. At least once, it already has: The following month, Republicans tried to preemptively purge some 225,000 North Carolina voters using the same theory. Myers, also the judge in that case, rejected it.

In any event, the legal intricacies of Griffin’s case are less revealing than the types of people it would exclude from democracy. According to an analysis conducted by the Raleigh News & Observer, about a quarter of voters targeted by his driver license-or-Social Security number scheme are between ages 18 and 25. Most are Democrats or unaffiliated with a political party. About 20 percent are Black, and since white voters in the state outnumber Black voters by three to one, Griffin’s challenge is about twice as likely to disenfranchise a Black voter as it is a white voter. As usual, Republican campaigns to protect “election integrity” just so happen to pare down the electorate to one that is older, whiter, and more Republican.

Riggs speaks to reporters outside the U.S. Supreme Court after oral argument in Moore v. Harper, December 2022 (Photo by OLIVIER DOULIERY/AFP via Getty Images)

Griffin frames his challenge as a matter of statutory compliance and fidelity to the state constitution. But stripped of the legal jargon, it is the same slurry of voter fraud conspiracy theories that Republicans have been parroting for decades. His insinuations about the dangers of incomplete paperwork evoke the fantasy of malevolent hordes stealing elections from Real Americans by voting in the names of dead people, brown people, convicted criminals, and people who never existed in the first place. His challenges to the legitimacy of mail-in ballots echo baseless right-wing fearmongering about the “blue shift,” which refers to the phenomenon of (mostly Democratic) mail-in votes causing (mostly Republican) “leads” in in-person voting to shrink or disappear in the days that follow. In 2020, Donald Trump made this lie the basis of his “rigged election” claims, recasting the simple process of counting votes as proof of a vast left-wing plot to rob him of victory.

Griffin might not be able to say this stuff with a straight face were it not for the U.S. Supreme Court, which never misses an opportunity to uphold a brutal voter suppression scheme in the name of protecting democracy. Under the leadership of Chief Justice John Roberts, the justices have upheld all manner of efforts to disenfranchise Democrats, people of color, or, when Republicans do their jobs especially well, both. They have allowed GOP-controlled state legislatures to purge voter rolls, invalidate ballots, erect insurmountable barriers to voting, and simply gerrymander undesirable voters out of existence. For all that Roberts has done to advance the conservative agenda, the steady evisceration of voting rights might be his most important accomplishment: Sure, Republicans won’t win every single fight, but for as long as the Court keeps a thumb on the scales of democracy, their odds are always improving.

Even if Riggs prevails, the next North Carolina Democrat in a close race might not be so lucky. After Democrats won statewide elections for governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general in 2024, the outgoing veto-proof Republican legislative majority passed a sweeping bill to strip the executive branch of many of its powers, as detailed by Alex Burness at Bolts. One provision transfers appointment authority for the elections board from the governor, Democrat Josh Stein, to the state auditor, Tim Boliek, who is—you guessed it—a Republican. Nothing says “we are serious about nonpartisan, common-sense good-government reform” like suddenly giving the power to appoint elections board members to your in-house accountant.

The Republican Party’s hijacking of North Carolina’s democracy and Jefferson Griffin’s brazen attempt to overturn an election he lost both reflect the prevailing conservative conception of America’s proper political order: one in which Republicans are the only legitimate rulers, entitled to govern in perpetuity. Any other result is inherently incorrect—the product of an error that requires immediate correction, a crime that merits swift punishment, or a loophole to close as expeditiously as possible, before any other undeserving interloper ever comes close to accidentally holding power again.

Along with the previous Democratic governor, Roy Cooper, Stein has challenged the law in court. But if it survives, future election disputes in North Carolina could be decided first by a Republican-controlled elections board, and then appealed to the Republican-controlled supreme court (and then, perhaps, to the Republican-controlled U.S. Supreme Court). It would create a quasi-permanent home-field advantage for aggrieved Republican candidates: a series of uniformly sympathetic forums in which they get to wink slyly while using decorous language to ask their friends for a little help getting them over the top. You do not need to be an elections expert to understand which party will get its way more often than not.

Correction: An earlier version of this posted stated that Black voters in the North Carolina outnumber white voters by three to one. The correct figure is that white voters in North Carolina outnumber Black voters by three to one.