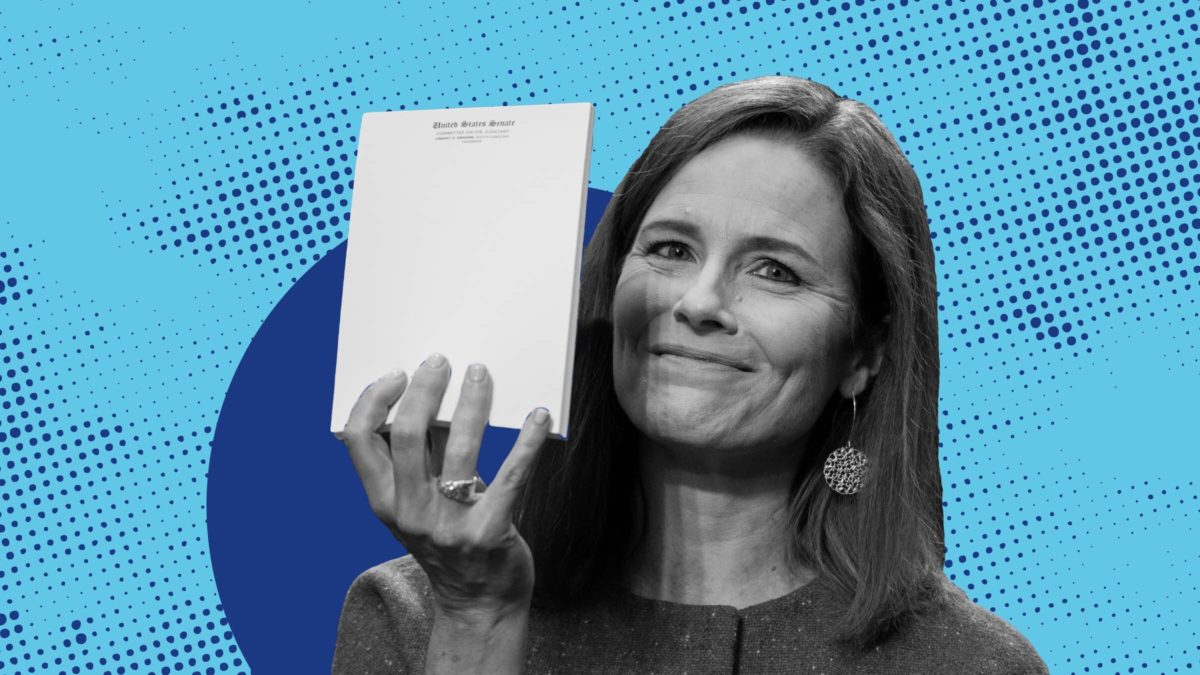

On Sunday, The New York Times published a lengthy profile of Justice Amy Coney Barrett, which described her as “more restrained” and “more deliberate” than her conservative colleagues, and concluded that she is “showing signs of leftward drift.” It noted, for example, that Barrett has parted ways “several times” with Justice Clarence Thomas, whom she believes “leans too heavily on history” when making decisions. For many legal journalists, few narratives are more alluring than framing a conservative Supreme Court justice as the Surprise Emerging Moderate anytime they come down somewhere to Sam Alito’s left.

Three days later, the Court decided United States v. Skrmetti, a constitutional challenge to a Tennessee law that prohibits doctors from providing gender-affirming healthcare to transgender minors. In an opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts, the Court upheld the ban on the grounds that it discriminates based on age and medical condition, which is legal, rather than on transgender status. But Roberts’s opinion explicitly declined to decide whether transgender status is a “suspect” or “quasi-suspect” class under the Equal Protection Clause in the first place. By doing so, he left the big question—settling on a legal standard for federal courts to use when analyzing anti-trans laws elsewhere—for another day.

Barrett, as if compelled to disprove the Times profile’s thesis as quickly and dramatically as possible, decided that Roberts did not go far enough. In a concurring opinion, she argued that transgender people are neither a suspect nor a quasi-suspect class—a determination that, if adopted by the Court, would give Republican lawmakers the green light to pass laws aimed at driving trans people out of existence. Barrett also pushed a legal theory that would freeze the Court’s equal protection jurisprudence in amber, forevermore preventing the law from even acknowledging emerging forms of bigotry, much less addressing them.

Alito argued for the same result in a separate concurrence, and took care to note that his and Barrett’s analyses merely “emphasize different points.” Thomas—who was, again, supposed to be Barrett’s unlikely foil roughly 72 hours ago—joined Barrett’s opinion in full.

The Fourteenth Amendment guarantees “equal protection of the laws” to everyone. But since many laws classify people on some basis, courts have developed a complex, multi-tiered system for determining when classifications are unconstitutional. To decide whether a group is a “suspect” class entitled to stronger legal protections, courts consider two factors: first, whether group members share “obvious” or “immutable” characteristics, and second, whether the group has faced discrimination “as a historical matter.” Under the Court’s precedent, biological sex is a “quasi-suspect” class, which means that courts subject laws that discriminate based on sex to “intermediate scrutiny”—not the hardest test to pass, but not a gimme, either.

In Skrmetti, the plaintiffs argued that transgender status is analogous to biological sex, and that laws that discriminate based on transgender status should thus be subject to intermediate scrutiny. For the justices, this is a big ask: The Court has been reluctant to recognize quasi-suspect classes other than sex, and has rejected requests that it extend these protections to poor people, older people, and disabled people, among others.

Barrett’s concurrence makes clear that she wants to slam the door on trans people, too. First, she argues, transgender status is not associated with “immutable” physical characteristics (for example, nonwhite skin). But even setting that aside, Barrett says that “private” discrimination against trangender people is not enough to make them a suspect class, because what matters is a history of “de jure” discrimination—legalese for discrimination of the official, formal sort. Women qualify for intermediate scrutiny in part, Barrett says, because they faced “more than a century’s worth of discrimination in the law,” and could not vote until 1920. And since the legal system has not (yet) treated transgender people as badly for as long, discriminating against them cannot, constitutionally speaking, be all that serious.

(Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images)

This section of Barrett’s opinion echoes her comments at oral argument in Skrmetti, when she asserted, to the surprise of anyone with access to Google, that no “history of de jure discrimination against transgender people” exists. This claim suggests that Barrett is unfamiliar with the 669 anti-trans bills introduced by state lawmakers in 2024 alone, or with criminal bans on cross-dressing that date to the mid-19th century, or, you know, the law at issue in this case. And as Justice Sonia Sotomayor notes in her dissent, if Barrett needs still more evidence of legal discrimination against trans people, she need look no further than the ongoing efforts of the president who appointed her, Donald Trump, to purge transgender people from military service. Barrett should know about this, since she and her fellow conservatives gave him permission to do so five weeks ago.

Going forward, Barrett says she would not recognize any new suspect classes absent a sufficiently voluminous history of de jure discrimination. “Courts are ill suited to conduct an open-ended inquiry into whether the volume of private discrimination exceeds some indeterminate threshold,” she writes. “By contrast, they are well equipped to analyze where there is a history of legislation that has discriminated against the group in question.”

For people who care about living in a country in which the Equal Protection Clause is more than an aspirational platitude, the problem with Barrett’s test is obvious: If evidence of private discrimination isn’t enough to qualify a group as a suspect or quasi-suspect class, laws that discriminate against that group will never fail under the Equal Protection Clause, because such laws will never be subject to more than “rational basis” review. (Put differently, it is hard to establish a “history” of illegal discrimination when courts repeatedly decline to hold that that discrimination is illegal.) When Barrett says she wouldn’t recognize new suspect classes without enough of a history of de jure discrimination, she is saying she is done recognizing suspect classes for good.

At one point, Barrett hedges a little, allowing that a “widespread history of state action that reflects animus” could, in theory, maybe, hypothetically give courts “good reason to be suspicious of the government’s motives.” But this is a hollow concession, because she also asserts that states are “entitled to a presumption that their actions turn on constitutionally legitimate motivations,” and reiterates that private discrimination would not provide a “basis for inferring that state actors are also likely to discriminate.” In practice, no new group seeking the protections of heightened scrutiny would be able to overcome this “presumption.” Under Barrett’s standard, judges would evaluate every law in the light most favorable to the state, subject it to the Court’s easiest test, and call it a day.

Maybe the most troubling section of Barrett’s opinion mentions, in passing, other types of laws that her logic would allow to stand: laws implicating “access to restrooms” and “eligibility for boys’ and girls’ sports teams,” which she characterizes as “areas of legitimate regulatory policy.” As Barrett undoubtedly knows, lawmakers who sponsor bathroom bills and trans sports bans always cite some pretext for acting other than rank transphobia. (Proposals to ban trans women from women’s sports are the only instance in which Republicans have ever given a shit about women’s sports.) What Barrett is signaling here is that she believes judges should accept these explanations at face value, and should not inquire any further.

Bad as the result in Skrmetti is, it could have been much worse: Right now, four federal appeals courts with jurisdiction over 23 states subject laws that discriminate based on transgender status to some form of heightened scrutiny, as the ACLU’s Josh Block notes. But at least three of the conservative justices are raring to upset this fragile status quo, and Barrett is emerging as their loudest, most strident champion. Her opinion in Skrmetti reveals many things about her; a “leftward drift” is not among them.