Another Supreme Court term has come and gone, which means it is once again time for law professors to write opinion columns revealing just how little they understand the subjects they are handsomely paid to teach.

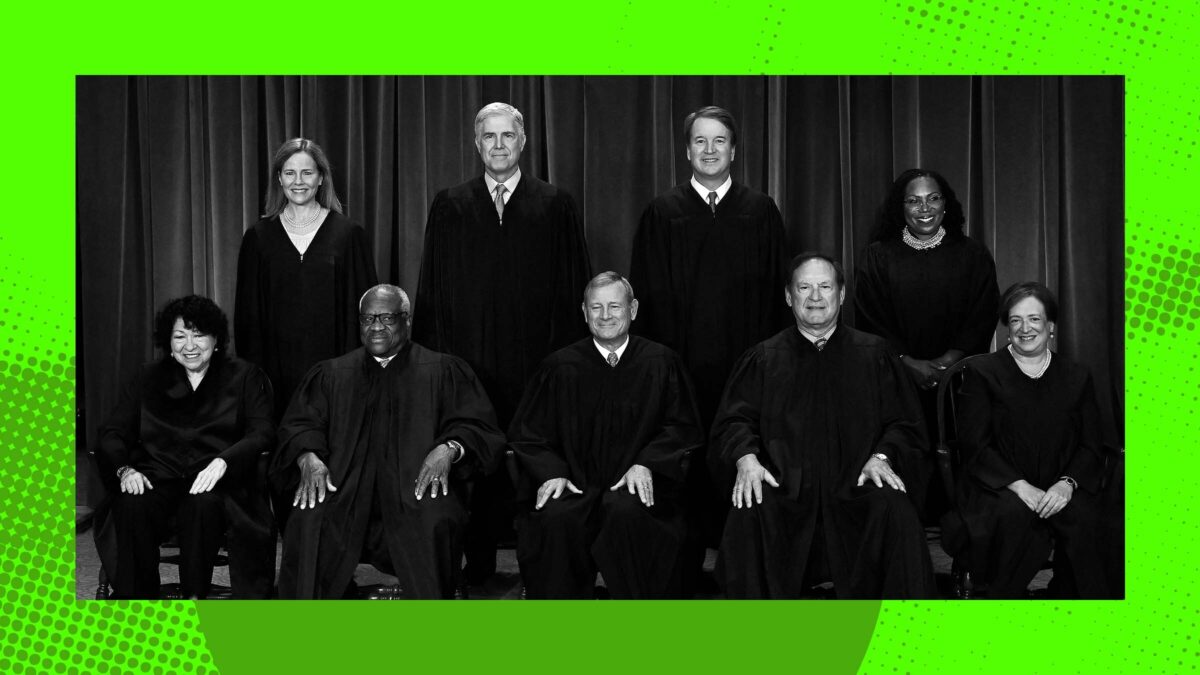

Among this year’s recappers is Harvard Law School’s chronically incorrect Noah Feldman, who in his Bloomberg column makes what I will characterize, for now, as an ambitious argument: that although the Court perhaps “further enabled” President Donald Trump by ending the term by issuing “a series of conservative decisions that [he] likes,” it “also simultaneously pursued a careful strategy aimed at preserving the rule of law in the face of Trump’s unprecedented challenges to it.” In other words, this six-justice Republican supermajority is not purposefully empowering a Republican president’s gleeful lawlessness. It is waiting for the perfect moment to put a stop to it.

Feldman’s column focuses on the Court’s recent shadow docket rulings related to Trump’s more creative assertions of executive power. There are many: Over the past few months, the Court, among other things, greenlit the Trump administration’s efforts to deport noncitizens to third countries without notice or a hearing; granted Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency staffers unfettered access to private Social Security data; permitted Trump to fire two members of independent federal agencies (notwithstanding federal law and Supreme Court precedent that prohibits him from doing so); and allowed Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth to purge the military of transgender servicemembers

On the term’s last day, the justices capped off this run with Trump v. CASA, rolling back a trio of lower court injunctions that had blocked the White House from implementing its executive order purporting to end the Fourteenth Amendment’s promise of birthright citizenship. For the children of nonpermanent residents, the result in CASA transforms what had been a 150-year-old constitutional right into, in effect, a privilege doled out by trial court judges on an ad hoc basis.

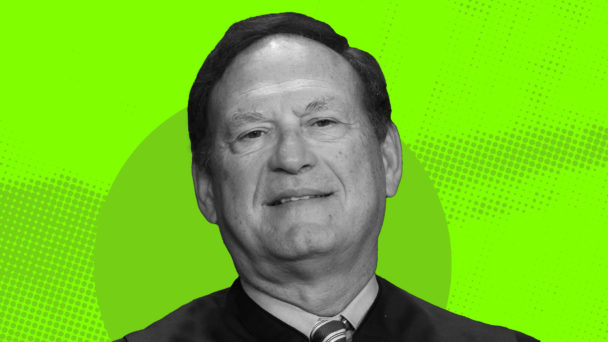

Feldman is careful to note that these decisions are bad, and that he does not support them. But, he continues, they are “not the most important element of the Supreme Court’s job since Trump took office,” because the Court’s “essential function” right now is to “fight for the preservation of rule of law.” For this reason, Feldman argues, Chief Justice John Roberts—that careful, savvy institutionalist—is picking his battles, blocking some of Trump’s executive orders while studiously avoiding conflicts that might prompt Trump to ignore a Court order he does not like.

Back in February, two weeks after Trump took the oath of office, Feldman reassured readers that Trump was “unlikely to defy a judicial decision,” because even the conservative justices would not “tolerate direct defiance of the authority of the judiciary.” Now, he writes that Trump has shown himself more willing to break the law than any previous president, and that in a “direct constitutional crisis triggered by defiance of judicial orders,” it is “hard to say with confidence that Trump wouldn’t win.” Apparently, the last few months have been sufficient to persuade Feldman that he was wrong about Trump’s interest in stuffing the Constitution in the garbage, but not about the Supreme Court’s interest in helping him out.

A “fair” assessment of the Court’s term, Feldman concludes, must evaluate not only the substance of its decisions, but also “how the Court is doing on the most consequential issue: keeping the Constitution alive.” His answer: “The Court is doing all right.”

(Photo by Nicolas Economou/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Among the several errors in Feldman’s essay, the simplest is his elision of the real-world consequences of cases that are, in his view, mere pieces on John Roberts’s eight-dimensional chess board. The nationwide injunctions case, for example, will soon thrust children born to nonpermanent residents into a constitutional gray zone, in which their right to U.S. citizenship hinges on whether their state’s attorney general happens to have joined a lawsuit in which a federal judge has entered an injunction capable of surviving appellate review. To the extent that Roberts is patiently watching a secret master plan unfold exactly as he hoped, I am not sure that parents whose infants can’t get Social Security numbers have any reason to give a shit.

Feldman also assumes that the Court’s decision to delay a confrontation with the White House will put the Court in the strongest position to force Trump’s surrender on the day that confrontation takes place. At one point, he compares lower court judges entering nationwide injunctions against Trump to “battlefield colonels” trying to “launch a major war.” By limiting the practice in CASA, Feldman argues, Roberts and company smartly reserved for themselves the power to make the “tactical and strategic decisions” about when and how to confront Trump, whom Feldman calls “the most dangerous adversary they’ve ever faced.”

I suppose it is natural for someone who has spent their career venerating the Court to imagine its fearless leader as in control of the situation all along, deftly luring his powerful but reckless opponent into an expertly laid jurisprudential trap. But absent from Feldman’s analysis is the possibility that by voluntarily surrendering more power to Trump with each passing week, the Court is encouraging him to engage in even more brazen displays of lawlessness, and creating more opportunities for him to one day shrug his shoulders and tell Roberts to go to hell. To extend Feldman’s war metaphor a bit, the argument for keeping your powder dry is not especially persuasive when doing so entails getting shot to death while you wait.

But Feldman’s most fundamental mistake is his apparent belief that the Court in fact intends to someday constrain Trump, which will come as a surprise to anyone who has watched the justices spend years passing up every meaningful opportunity to do so. These are the same justices who rewrote the Insurrection Clause to rescue Trump from exclusion from the 2024 ballot. They are the same justices who created a sweeping doctrine of presidential immunity to rescue him from criminal prosecution. And now that he is president again, they have handed him the power to launch a soft repeal of the Fourteenth Amendment, subject only to lower courts’ ability to bind the litigants in the specific cases that appear on their dockets. For all the time Feldman spends outlining the perils of a bona fide constitutional crisis, he does not even gesture at the Court’s starring role in fomenting it.

If Feldman is wrong—if the Court struck down universal injunctions in order to open the door to enforcement of Trump’s most illegal stunt yet—then the justices are accomplices, hastening the end of this country’s experiment with representative democracy one 6-3 opinion at a time. And even if he is right—if the Court compromised on the Constitution’s guarantee of birthright citizenship so that it could live to fight some other day—the justices are not, as Feldman’s headline asserts, “playing the long game.” They are cowards who have already given up.

Noah Feldman is only one among many legal pundits struggling to explain how a Court controlled by a six-justice conservative supermajority implementing a reactionary policy agenda is nevertheless Doing Law, Not Politics. But rarely do pundits so stubbornly insist on casting the justices as the story’s principled heroes when the justices themselves have made abundantly clear that they are something else.