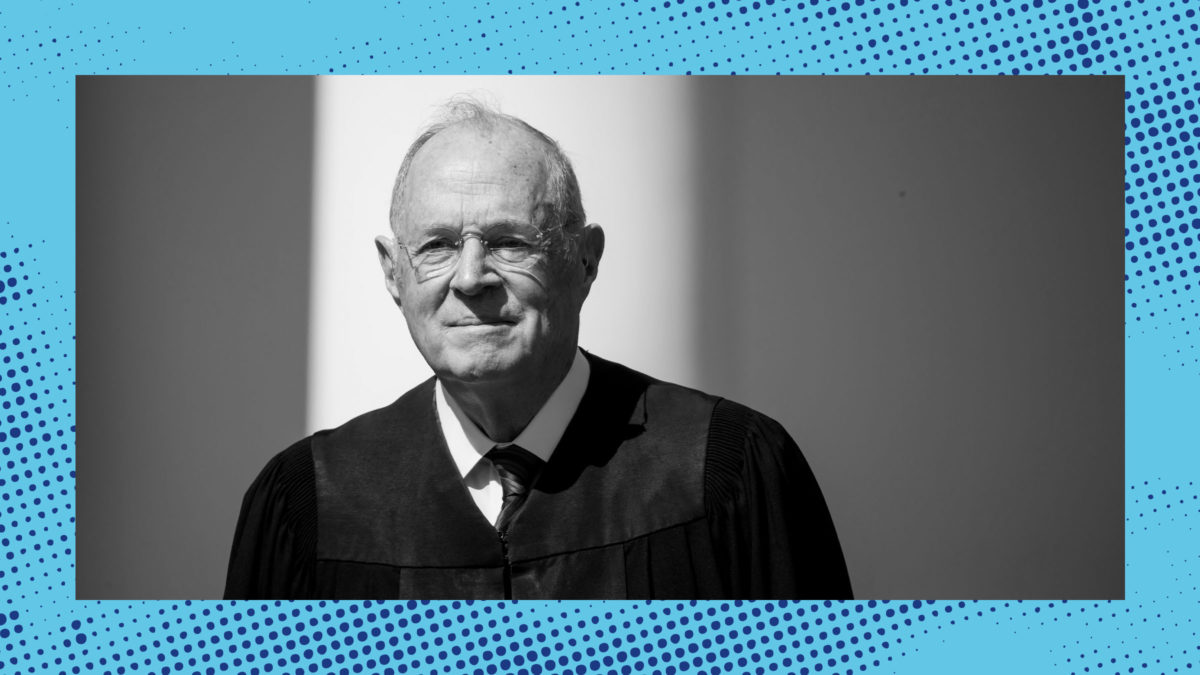

Since stepping down from the Supreme Court in 2018, Justice Anthony Kennedy has largely stayed out of the public eye—that is, until the publicity cycle for his new memoir, Life, Law & Liberty, kicked up over the last few weeks. Suddenly, he has something to say; unfortunately, his comments don’t have much value in this crisis moment for the Court, and for the millions of us who are subject to its whims.

First, Kennedy wagged a finger at the Court while talking to NPR’s Nina Totenberg: “My concern is that the court in its own opinions…has to be asked to moderate and become much more respectful,” he said. (One assumes he means the liberal justices unwilling to let major precedents go without calling out the conservative supermajority for its radicalism.) To Adam Liptak of The New York Times, Kennedy expressed vague angst about the justices’ hyperactive shadow docket, saying that the Court “has to do the best that it can,” but that it “does need time” to do its work.

These tedious morsels accurately prefigure Life, Law & Liberty, which combines childhood remembrances with Kennedy’s dull recitation of his views—views too variegated to cohere into a philosophy. One does not find in this book a heretofore hidden coherence to Kennedy’s approach to deciding cases, which he seems to think has never failed. In the years since, we have all seen the disastrous consequences of Kennedy’s major opinions, from Citizens United to Masterpiece Cakeshop to Bush v. Gore. (The Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore was unsigned, but in the book, Kennedy confirms he wrote it.) But Life, Law & Liberty reveals that Kennedy still hasn’t looked at what he wrought while on Court—or that he’s never cared to think about it.

Kennedy speaks alongside President Ronald Reagan Judge after his nomination to the Supreme Court, November 1987 (Photo by Dirck Halstead/Getty Images)

Despite Kennedy’s enmeshment within political systems—he became friends with Ronald Reagan in the mid-1960s, when mutual acquaintances introduced them during Reagan’s first run for California governor—he rarely, if ever, explores the connections between the law and politics. Indeed, based on this book, one would never know that Kennedy was a Republican but for his friendship with Reagan. That cozy relationship led to his nomination by President Gerald Ford to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, and later to the U.S. Supreme Court in Reagan’s second term, in the wake of the failed nomination of Robert Bork.

Throughout his discussions of his earlier career, though, Kennedy disclaims any strategic agenda. He claims he declined to adopt either an originalist or pragmatic approach to constitutional cases because “it seemed unwise.” Having a “rigid standard in every case” would contradict his self-image as an idealistic, family-oriented attorney who just happened to become one of the most powerful figures in the federal government.

It seems an occupational hazard that everyone who ascends to the Supreme Court becomes a less rigorous writer and thinker. And once Judge Kennedy goes to Washington, we begin the familiar Supreme Court justice book ritual of the warm and happy relationships the justice has with each of their colleagues. Apparently it is possible to work with 16 people over the course of nearly 30 years, taking high-stakes votes and writing opinions that reshape American society, and never once have a major disagreement.

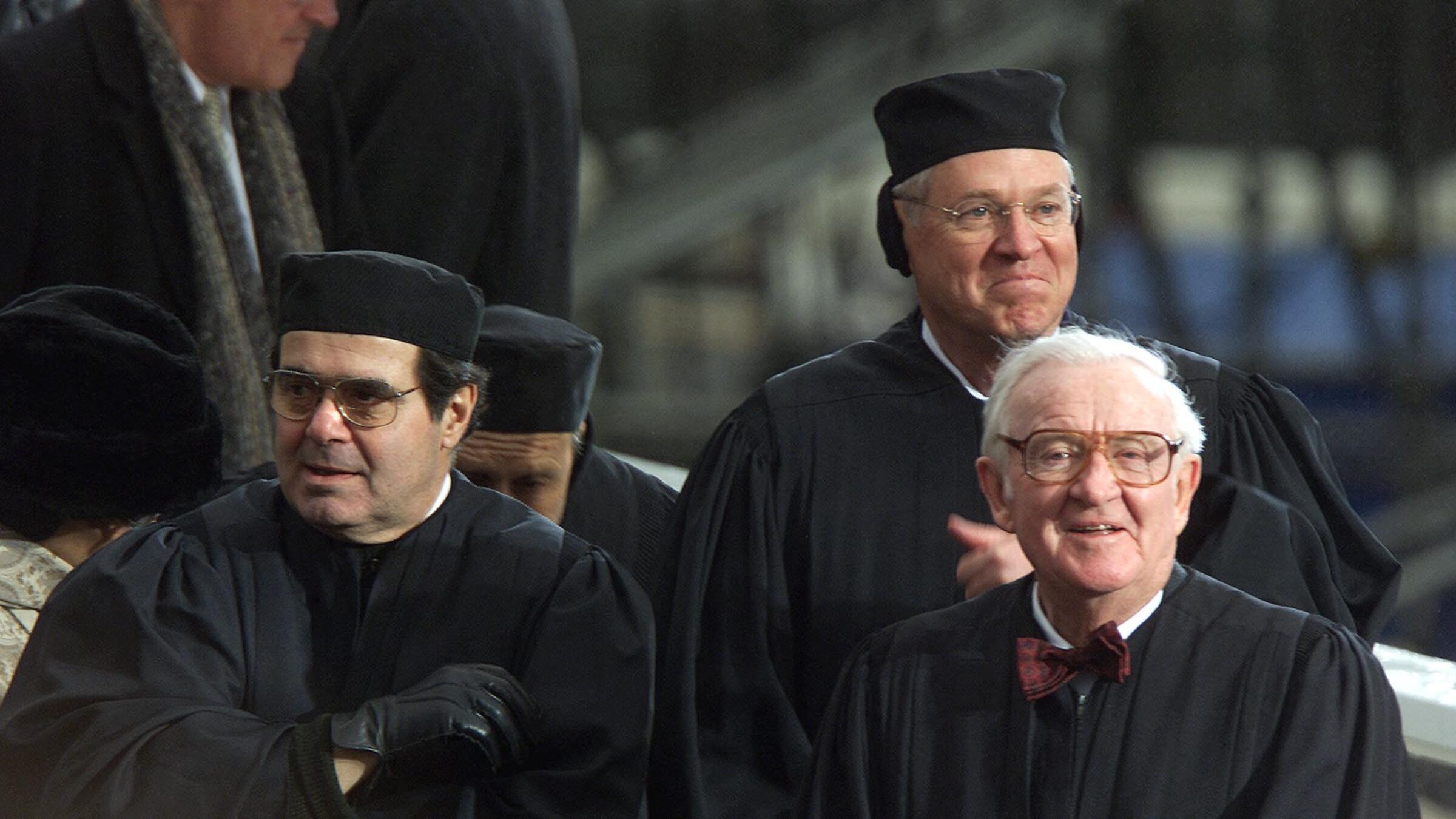

Even the most famous incident of discord that Kennedy recounts in the book—a spat with Justice Antonin Scalia—has the soft focus of a soap opera and the mushy dialogue of a bad romance novel. Kennedy’s 2015 majority opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges, which established a constitutional right to same-sex marriage, elicited four furious dissents, including a screed from Scalia, who could not refrain from launching incessant attacks against Kennedy’s opinion, calling it “pretentious,” “egoistic,” and “profoundly incoherent.” Famously, Scalia wrote in a footnote that Kennedy’s majority indicated that the Court had “descended from the disciplined legal reasoning of John Marshall and Joseph Story to the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie.” Just a little trash talk among friends in the U.S. Reports, I suppose.

Unsurprisingly, that language created a rift between Scalia and his colleagues, one that apparently troubled Kennedy and his brethren for months. No need to worry: Kennedy says that he and Nino finally hugged it out in February 2016, shortly before Scalia’s sudden death at a Texas ranch. The dialogue that Kennedy recounts—literally, he provides it in the book in script format—would embarrass even the most eager theater kid: According to Kennedy, their parting conversation ended with Scalia saying, “Tony, this is my last long trip.” Did you catch the foreshadowing? We’re a far cry from “I knew it was you, Fredo.”

Justices Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy, and John Paul Stevens and the swearing-in ceremony for President-elect George W. Bush, January 2001 (Photo by TIM SLOAN/AFP via Getty Images)

The book sputters to a close with chapters that touch on various legal doctrines—free speech, juvenile life sentences, abortion, prisons—in which Kennedy describes his own views divorced from meaningful analysis or consideration of counterarguments. For example, Kennedy recounts the grand bargain by which he and Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and David Souter drafted a joint opinion in 1992 in Planned Parenthood v. Casey that preserved the core holding of Roe v. Wade.

But he repeatedly declines to contextualize these memories in any political, social, or historical milieu; the only abortion case Kennedy discusses after Casey is Gonzalez v. Carhart, in which Kennedy’s 2007 majority opinion upheld a federal “partial birth abortion” ban in an opinion that invoked the “regret” of those who seek such reproductive care. Kennedy apparently lives in a world in which Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which in 2022 overturned Roe and his Casey compromise, doesn’t exist. For judges like Kennedy, cases exist in amber separate from the world.

Or consider Kennedy’s discussion of Bush v. Gore, which focuses on that case’s frantic timeline and the ostensibly urgent need for the Court’s intervention in a hotly contested election dispute. Kennedy never discusses the optics of the five most conservative, Republican-appointed justices opting to hand the presidency to Bush in an opinion that found an equal protection problem with Florida’s vote counting, but also told lower courts and plaintiffs to never cite the case again. One might think that, with some distance from the decision and the freedom to speak more directly after discarding his robes, Kennedy would consider the dynamics of the Electoral College, or the troubling aspects of a supposedly apolitical branch acting so brazenly in a political context. Guess again.

What makes these Supreme Court memoirs so unnecessary is their authors’ inability or refusal to engage with the consequences of their work or the choices that they make. Kennedy’s version of Citizens United fails to acknowledge his libertarian perspective on speech regulation, and only glancingly acknowledges the repercussions of a decision that today allows for unlimited independent spending on campaigns. Kennedy also declines to engage with the failure of his preferred remedy—transparency—to affect these massive contributions; in his view, the solution to the current problems with elections is encouraging the polity “to be informed and involved in preserving our freedom.” Hard to think that an “informed citizenry” can defeat the plutocrats who used dark money to funnel over a billion dollars into the 2024 election cycle.

For sitting justices, one can argue that avoidance stems from concerns about the propriety of opining on legal issues that might someday come before them. But for retirees, there’s nothing stopping them from admitting error or a change of perspective. Four years after stepping down, Lewis Powell famously admitted to his biographer that he regretted his vote in McCleskey v. Kemp, in which his majority opinion held that statistical evidence of racial disparities in sentencing did not matter for the purposes of reversing a criminal conviction. While Powell’s regret doesn’t help any of the defendants imprisoned or murdered by a racist criminal system, it at least acknowledges that judges and justices make errors, and that those errors can have massive consequences, and that Powell had learned to question his decisions.

But at the close of his memoir, it appears that Anthony Kennedy, Powell’s successor on the Court, has learned nothing. His decisions were right; his views made sense; he does not care that his successors have undermined the constitutional order. One of the most poignant moments in Life, Law & Liberty occurs in Kennedy’s childhood and remains chilling over eighty years later: A young Japanese American friend, around six years old like young Tony, gave him a treasured samurai warrior doll on his way to the internment camps during World War II. “We never saw or heard from him again,” Kennedy notes mournfully.

I immediately thought of Trump v. Hawaii—the 2018 case in which Kennedy concurred with John Roberts’ majority opinion upholding Trump’s Muslim ban—and wondered if Kennedy himself made that connection. That was my mistake: The book does not even mention Trump v. Hawaii, let alone Kennedy’s shameful role in ratifying a repugnant government policy similar to the internment camps he remembers from his childhood. This is not a book of regret or even reflection; it is an unexamined life of gauzy memories.