The Trump administration published a proposed rule on Monday that would redefine the term “waters of the United States” as Congress used it in the Clean Water Act. The change would revoke the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s authority to protect tens of millions of acres of wetlands and millions of miles of streams.

Congress enacted the CWA in 1972 to restore the integrity of the nation’s waters following years of unchecked pollution that occasionally resulted in rivers catching on fire. However, Congress did not precisely state what those regulated “waters of the United States” are, and instead left that up to the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers, which issues permits for projects that impact the country’s water. The answers to questions like whether, where, and when businesses can discharge pollutants into the nation’s water—and how much pollution is too much—all turn on how the term “waters” is defined. So, corporations and environmentalists have been fighting over the definition’s scope for decades, especially with respect to wetlands—the swampy, low-lying areas where land and water meet—and small or seasonal streams.

Trump’s proposed rule would be (pardon the phrase) a sea change in Clean Water Act enforcement. Going forward, it would limit the federal government’s jurisdiction to “standing or continuously flowing bodies of surface water,” ruling out many streams that don’t flow year-round. It would further require “wetlands” to have a “continuous surface connection” to “relatively permanent” bodies of water, cutting out nearly all non-tidal wetlands in the contiguous United States.

Wetlands and intermittent streams perform critical functions like filtering pollution, controlling flooding, and improving the quality of water. The Natural Resources Defense Council estimates that the change would strip federal protections from 85 percent of wetlands nationwide.

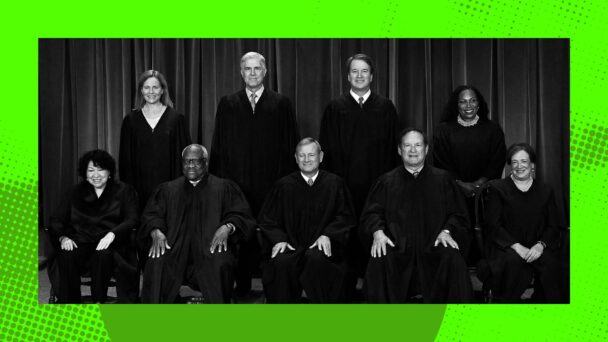

The proposed rule is a victory for polluters, and the Supreme Court made it possible. For decades, the EPA broadly interpreted the Clean Water Act to include the authority to regulate wetlands “adjacent” to waters that could affect interstate or foreign commerce, and read “adjacent” to mean “bordering, contiguous, or neighboring.” But in 2023, the Court decided in Sackett v. EPA that “neighboring” doesn’t cut it, and took the opportunity to create a new two-part test that narrowed the definition of wetlands.

Writing for the majority in Sackett, Justice Samuel Alito said that in order for an “adjacent wetland” to be covered by the Clean Water Act, it must be adjacent to a “relatively permanent body of water connected to traditional interstate navigable waters.” Second, the wetland must have “a continuous surface connection with that water”—basically, the wetland must be indistinguishable from the body of water it is adjacent to.

Readers should recognize that “relatively permanent” and “continuous surface connection” language: The Trump administration lifted it directly for the proposed rule, which it says is “intended to adhere faithfully to the Supreme Court’s direction.”

On Monday, EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin practically thanked Alito for the assist, and expressed confidence that this rule would survive legal challenges. “That’s one of the big differences from the past, is that you have the Supreme Court weighing in, and we’re following Sackett very closely,” he said. The Natural Resources Defense Council took a different view, calling the proposal “an extreme and unscientific exploitation of an already extreme and unscientific Supreme Court ruling.”

This is hardly the first time that Republicans without robes have taken their cues from the Republicans with robes. And Zeldin’s remarks show how confident Republicans are in their strategy. The Trump administration and the Court are engaged in an ongoing dialogue, each inviting the other to go a bit further, continuously eroding the foundations of laws that keep people safe.