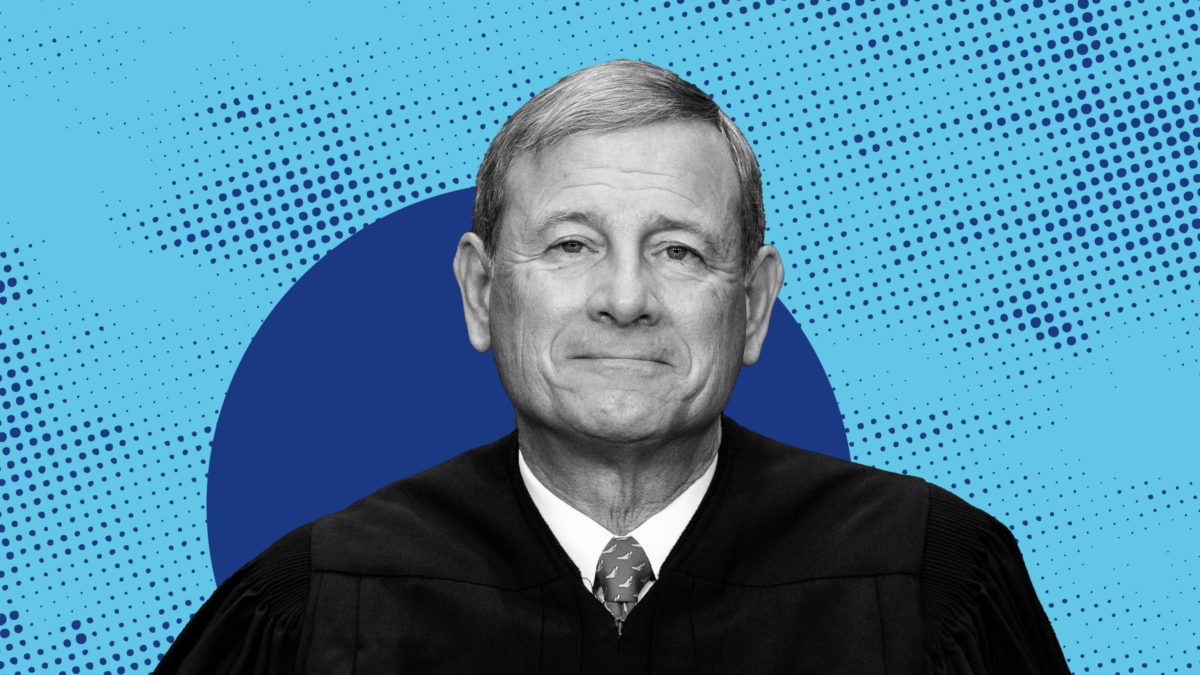

A five-justice majority of the Supreme Court ruled Wednesday that candidates for federal office have a right to challenge election rules in federal court, simply by virtue of being candidates. “Candidates have a concrete and particularized interest in the rules that govern the counting of votes in their elections,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts.

Justices Amy Coney Barrett and Elena Kagan concurred in the judgment, applying the traditional principle that anyone, including candidates, can sue if a law injures them in some way—for example, by imposing a monetary cost. But the rest of the conservative bloc, whose members made up the majority in Bost v. Illinois Board of Elections, took a different approach. Under the majority’s new standard, candidates may sue over election rules “regardless” of “whether those rules harm their electoral prospects or increase the cost of their campaigns.”

Bost constructs a VIP entrance to federal court just for politicians who want to challenge election rules. And it does so at the same time as Republicans across the country are filing more and more lawsuits that undermine the democratic process by (among many other things) purging registered voters from voter rolls, rejecting valid ballots over clerical errors, and even throwing out election results. The Court’s decision makes it easier for Republican candidates to sue when they want to exclude people from the electorate, and risks making election outcomes depend even more on court cases and less on the consent of the governed.

To be clear, at this stage of Bost, the Court is not deciding whether any particular election rule is legal; it’s deciding whether federal courts can hear lawsuits over such rules at all. Article III of the Constitution limits federal courts’ jurisdiction to actual “cases” and “controversies.” And one of the ways courts enforce that, in theory, is by requiring that would-be plaintiffs have “standing.” This means they must have experienced an actual, particularized injury that a defendant caused and a court can fix.

Several of the attempts by President Donald Trump and allies to overturn his 2020 election loss via litigation failed because courts concluded Trump and company didn’t have standing. And Trump has criticized the principle as a “technicality” that purportedly cost him the 2020 election. “Can you imagine a system where a person in an election doesn’t have standing, the president of the United States doesn’t have standing?” he asked during a debate in 2024. “That’s how we lost.”

The Supreme Court’s decision in Bost adopts Trump’s theory, and ensures that candidates like him who want to challenge rules related to counting votes literally have a standing invitation to federal court. Regular people have to clear high hurdles to get federal courts to hear their cases, but if you’re a Republican, you need only get on a ballot.

The candidate in this particular case is Michael Bost, a Republican from Illinois who has served in the U.S. House of Representatives since 2015. Like dozens of other states, Illinois accepts and counts some ballots that were mailed by Election Day but received after that day. Bost argues that this policy is unlawful, and filed a lawsuit in 2022 to block the state’s board of elections from counting those ballots. Bost contended that Illinois harmed candidates by including “untimely and illegal ballots” in its vote tallies, and making campaigns like his spend more resources when the election should have been over already.

Rep. Mike Bost, September 2022 (Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

The lower courts kicked the case to the curb, finding that Bost’s grievances were too speculative and too generalized—basically, that there was no way to know whether ballots arriving after Election Day would cost Bost the election, or money, or anything at all. And everyone has an interest in the proper application of election laws, not just candidates.

The Supreme Court now says otherwise. Candidates for elected office are different, Roberts writes in Bost, because “they have an obvious personal stake in how the result is determined and regarded.” Roberts likens people running for office to people running in a track meet: “Each runner in a 100-meter dash, for example, would suffer if the race were unexpectedly extended to 105 meters,” thus depriving them of the “chance to compete for the prize that the rules define,” he writes. Voters, whom the Court has not categorically welcomed to contest election rules in federal court, are mere spectators in the stadium.

In a dissent joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson criticized the majority’s “bespoke” rule for candidates for devaluing the public’s interest in free and fair elections. “Lest we forget: In a democracy, elections are not mere candidate-centered bouts,” she says. “Rather, they determine the fate of the community.” Yet Bost portrays candidates as having a unique legal interest in democratic governance, which, Jackson says, is backwards: “When what is at stake is the overall fairness of the electoral process, it is the people’s shared interest in democracy itself (and not just the candidate’s job prospects) that hangs in the balance,” she writes.

Jackson’s dissent also emphasized that the Court’s selective application of standing has practical, often painful consequences, highlighting the Court’s 1983 ruling in Los Angeles v. Lyons. After Los Angeles Police Department officers subjected Adolph Lyons to a life-threatening chokehold during a traffic stop, Lyons sued to prevent them from doing so to him or anyone else. And as Jackson notes, the Court held that Lyons didn’t have standing, reasoning—in spite of Lyons’s “appeals to fairness or common sense”—that he “failed to establish a real and immediate threat of future harm.” Lyons’ ripple effects are still felt today: Justice Brett Kavanaugh invoked the case in his infamous concurrence in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo, concluding that Latino victims of racial profiling did not have standing to sue the Trump administration because they had “no good basis” to believe they would be illegally stopped again in the future.

The lax approach to standing that the Court takes in Bost would have been helpful if applied in Lyons, to curb police brutality. It would have been helpful if applied in Noem, to block racist immigration enforcement. Instead, the Court only applies it here, to disenfranchise Americans who vote by mail. The Republican majority on the Supreme Court uses standing to make sure people they like can do anything they want, and people they don’t like can’t do anything about it.