On Thursday, the Supreme Court handed down its ruling in Cameron v. EMW Women’s Surgical Center, a case that is technically about whether Kentucky’s attorney general can intervene in a particular federal lawsuit. It is also about something far more consequential: whether conservative politicians can use the legal system to circumvent the results of democratic processes and undermine transitions of power.

In 2018, two doctors at EMW Women’s Surgical Center sued a host of Kentucky state officials, including then-Attorney General Andy Beshear, to stop enforcement of a new state law that effectively prohibited a common abortion method. Both sides quickly agreed to dismiss Beshear from the suit, though, and litigation proceeded instead against the state’s Secretary for Health and Family Services. After a federal district court ruled in the doctors’ favor and found Kentucky’s law unconstitutional, the secretary appealed.

Before the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals could hear the case, however, Kentucky elected Beshear, a pro-choice Democrat, as its new governor, and Daniel Cameron, an anti-choice Republican, as its new attorney general. Beshear, unsurprisingly, appointed a new secretary, who declined to defend the law any further after the appeals court upheld the district court’s ruling. Cameron found this unacceptable and argued that he should be entitled to intervene on his own, notwithstanding his predecessor’s voluntary exit from the lawsuit. Doing so could, in theory, allow a rising Republican star the chance to defend an anti-choice law before a conservative Supreme Court supermajority that had since added Justice Amy Coney Barrett to the bench.

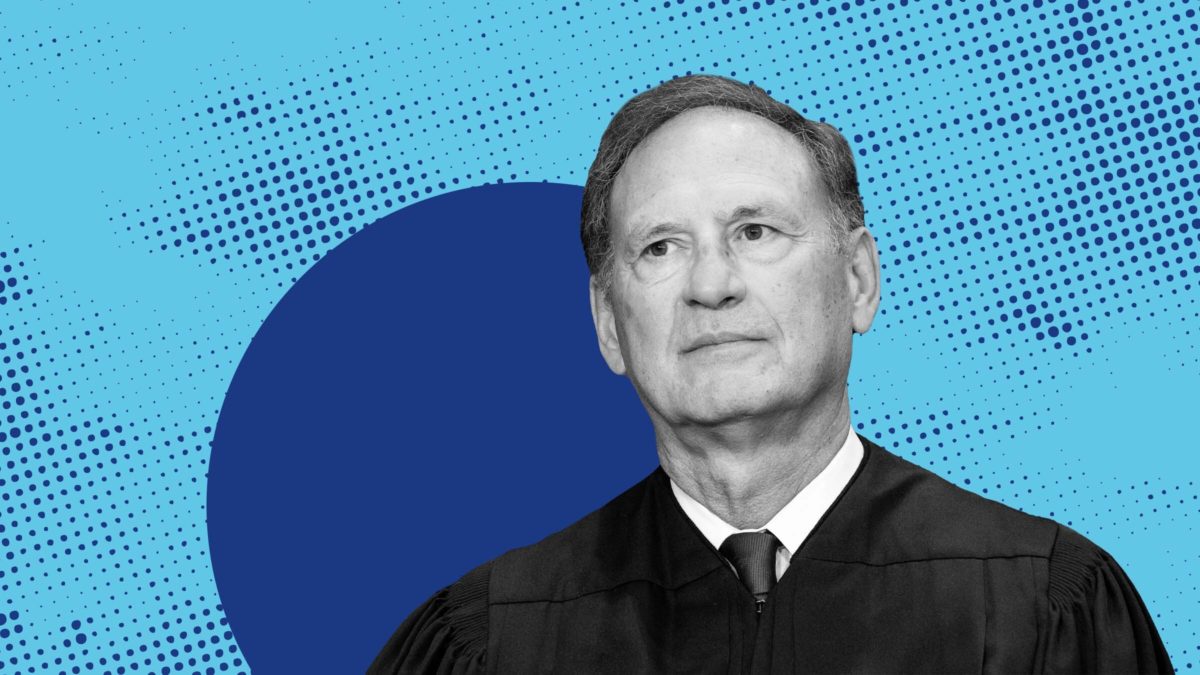

Writing for the six conservatives, Justice Samuel Alito gave him the go-ahead. “In defending the Kentucky law, the attorney general asserts a substantial legal interest that sounds in deeper, constitutional considerations,” he wrote. The majority argued that the Court was performing the vital function of preserving state sovereignty by affording multiple state officials the power to defend state laws in court. He put little stock in the decision of Kentuckians to elect a pro-choice governor, or in the new administration’s authority to decide not to defend an unconstitutional law any further. “Respondents may have hoped that the new Governor would appoint a secretary who would give up the defense of [the law],” Alito wrote, “but they had no legally cognizable expectation that the secretary he chose or the newly elected attorney general would do so.”

In a separate opinion joined by Justice Stephen Breyer, Justice Elana Kagan concurred in the judgment but questioned the Court’s sweeping declaration that Cameron has some kind of profound sacred right to intervene in the name of state sovereignty. “I see no reason to cast the analysis, even partially, in constitutional terms,” she wrote.

Only Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissented, criticizing the majority for bending over backwards to give Cameron his way. “I fear today’s decision will open the floodgates for government officials to evade the consequences of litigation made by their predecessors of different political parties,” she wrote. “Shifts in the political winds do not support a special carveout to longstanding principles of estoppel.”

As Sotomayor notes, this case presents an example of a favored tactic of conservatives: using “states’ rights” as a thinly-veiled justification for intervening in policy decisions with which the party disagrees. The January 6 insurrection was an extreme example of Republican willingness to fight an electoral outcome they don’t like. But the tactical maneuvers on display in Cameron, although considerably subtler, are also about preventing the opposing party from transitioning into power. Instead of allowing a governor to govern, the Court found a state official willing to fight for the law and affirmed his authority to do so. Elections have consequences, unless those consequences jeopardize a policy the conservative justices personally like.

Republican politicians in other states are likely to follow the Court’s lead here. The state of Arizona, joined by 20 other states, wrote an amicus brief in Cameron arguing that activist attorneys general should have sweeping authority to defend state laws. Arizona’s attorney general, Mark Brnovich, has frequently sought to expand his power when it comes to issues like abortion and immigration. Just last week, he was arguing before the Court that he should be able to intervene in a lawsuit against the City of San Francisco to defend a Trump-era immigration policy that President Joe Biden’s administration subsequently rescinded. Does this have anything to do with the state of Arizona? Not really. But the Court was willing to hear his argument anyway.

By ruling in Cameron’s favor, the justices endorse a strategy that circumvents democratic processes in order to give anti-choice activists another day in court. In doing so, the Court strengthens the case of conservative attorneys general seeking to defend unpopular policies, knowing they have allies in the judiciary who are rooting for their success.