Karl Brandt’s lawyer was stuck trying to defend the indefensible. Brandt, a high-ranking aide to Adolf Hitler who had also served as his personal physician, was one of several Nazi doctors on trial for crimes against humanity in the aftermath of World War II. A military tribunal had charged Brandt with, among many other atrocities, forcibly sterilizing thousands of people held in concentration camps during World War II. He was also a driving force behind Aktion T4, a program that resulted in the systematic murder of more than a quarter-million physically and mentally disabled people in an effort to purge them from the Aryan race.

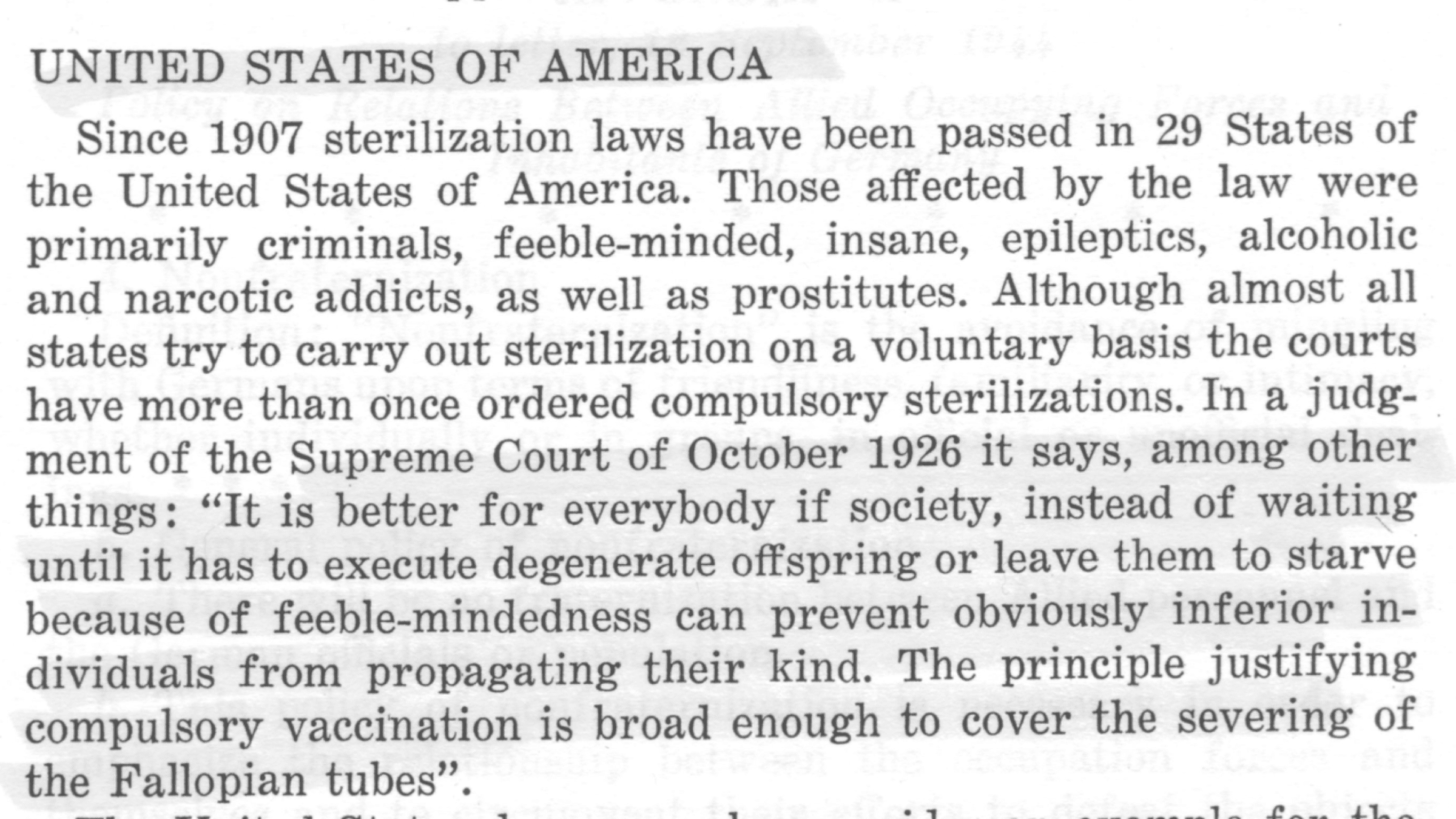

In their court filings at Nuremberg, though, Brandt’s team asked the judges a simple question: How bad could Nazi Germany’s mandatory sterilization program have been, really, if mandatory sterilization programs in America had earned the endorsement of none other than the U.S. Supreme Court?

Screenshot via Georgia State University College of Law

That quote is from Buck v. Bell, a Supreme Court decision that upheld a Virginia law authorizing the forced sterilization of “mental defectives” to promote “the health of the patient and the welfare of society.” The first person state officials sought to sterilize was Carrie Buck, who had given birth at age 18 after being raped by her foster parents’ nephew. Embarrassed, Carrie’s foster family persuaded a judge to declare her “feeble minded”—the same dubious label applied to Carrie’s mother, Emma, who had been committed several years earlier. Carrie was stripped of custody of her newborn daughter, Vivian, who was adopted by her foster parents on the condition that they be allowed to commit her if, as they suspected, she proved to be feeble-minded, too. Carrie was then shipped off to a state facility, where officials sought permission to surgically prevent her from ever having children again.

By a vote of 8-1, the Court granted Virginia’s request. In his majority opinion, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. compared the noble sacrifices of victims of forced sterilization to the noble sacrifices of U.S. soldiers killed in combat, pausing briefly during this wildly offensive analogy to suggest that someone like Carrie might welcome a mandatory salpingectomy as a blessing in disguise. “We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives,” he wrote. “It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence.”

Holmes concluded as follows: “Three generations of imbeciles is enough.” Carrie Buck was sterilized a few months later.

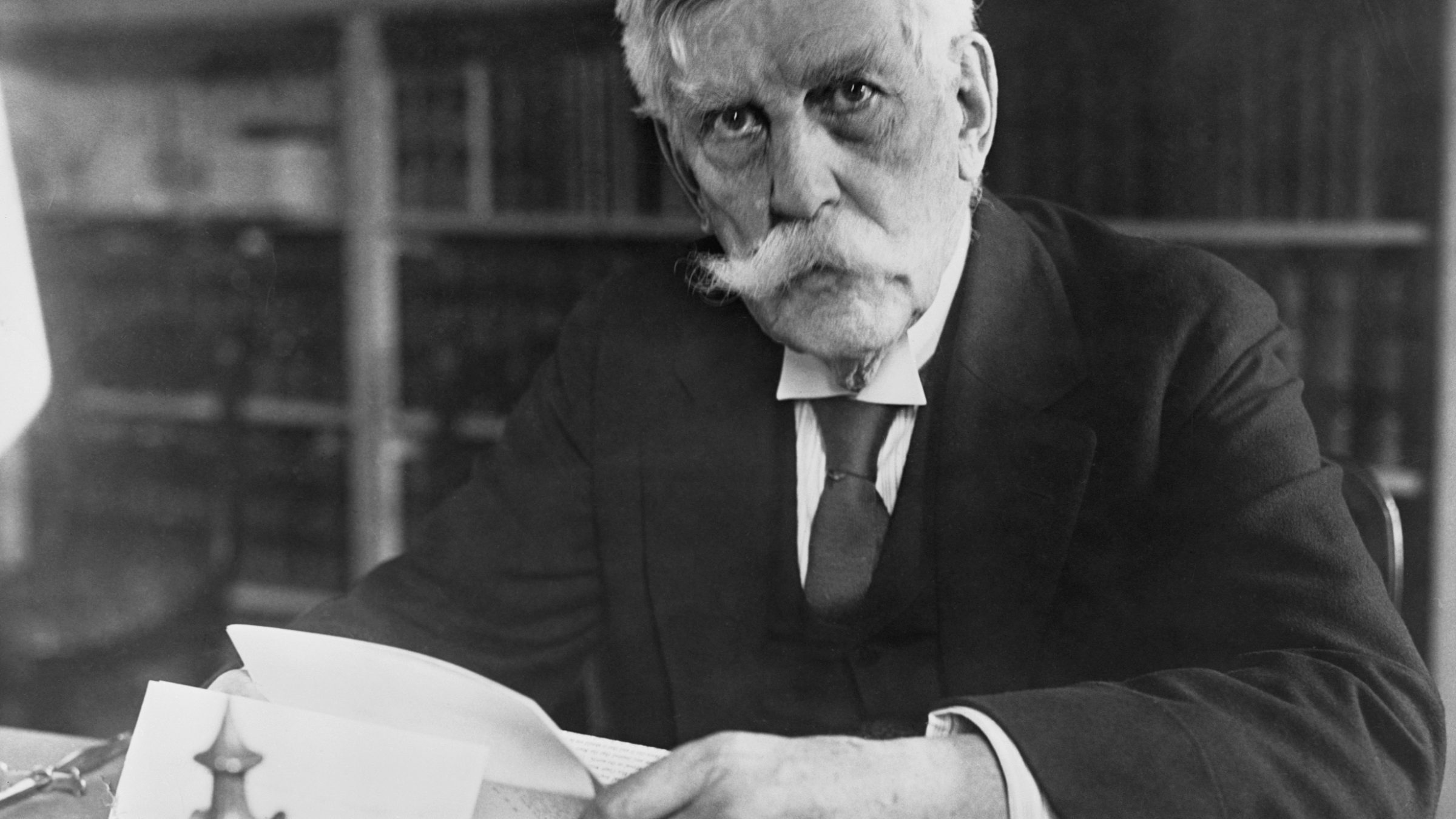

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (Getty Images)

Brandt’s ambitious invocation of Bell did not get him the result for which he’d hoped: He was found guilty, sentenced to death, and executed in 1948. But the fact that one of the most infamous Nazi war criminals was able to cite America’s highest court in his defense is among the most enduring stains on an institution that has earned a multitude of them. As is the case with many of the Court’s most shameful decisions, nearly 100 years after deciding Buck v. Bell, the justices have yet to formally overrule it.

With the Court’s blessing in Bell, states went on to sterilize an estimated 70,000 people in the decades that followed. Among them was Carrie’s 16-year-old sister Doris, also committed for her alleged feeble-mindedness and promiscuity, who was told that her surgery was an appendectomy by the doctors who performed it. Doris did not learn the truth about why she and her husband were never able to have children until 40 years later.

Vivian, Carrie’s daughter, was a decent student who even made the honor roll one term. She died of an illness at age 8.

After her release from custody, Carrie Buck lived as full a life as she could under the circumstances: She married in 1932, and remarried after her first husband’s death. She was described as a devoted wife and sister who loved to read newspapers—and, contrary to the state’s claims, as a woman of “obviously normal intelligence.” When she died in 1983, she was buried, by chance, in the same graveyard as Vivian, the daughter she never knew.

In the final years of her life, Carrie Buck reflected on how she hadn’t wanted a big family of her own. “A couple children,” she said, would have been enough.

Carrie and Emma Buck photographed together in 1924 (Arthur Estabrook via Creative Commons)

As always, you can find us at ballsandstrikes.org, or follow us on Twitter at @ballsstrikes, or get in touch via [email protected]. Thanks for reading.

This Week In Balls & Strikes

The Case For Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan Calling It Quits, Peter Shamshiri

These justices are important. But they are important because of the values they champion.

Conservative SCOTUS Justices Want to Make the Right to Strike Meaningless, Yvette Borja

Support for labor unions is at its highest point in decades. Enter the Supreme Court.

Michigan Supreme Court Justice “Completely Disgusted” By Concept Of Working With Formerly Incarcerated People, Madiba Dennie

In the U.S. legal system, some “experiences” are welcome and some are not.

How Anthony Kennedy’s Defense of Same-Sex Marriage Is Already Backfiring, Lisa Needham

In his Obergefell opinion, Kennedy went out of his way to acknowledge the beliefs of those who disagreed with him. Whoops.

This Week In Other Stuff We Appreciated

The Supreme Court’s Conservative Supermajority May Sabotage Unions’ Right to Strike, Terri Gerstein and Jenny Hunter, Slate

Glacier Northwest is an attack on worker power with frightening implications for American democracy.

The Legal Loophole That Could Arm Mass Shooters With Makeshift Automatic Rifles, Ian Millhiser, Vox

The case at the intersection of the Court’s anti-regulation and pro-gun bents.

The Supreme Court Is More Diverse Than Ever. But the Lawyers Who Argue Before It? Mostly White Men, John Fritze, USA Today

About a fifth of Supreme Court advocates are women. Fewer than 10 percent are Black or Hispanic.

This Week In Obscure Photos of Supreme Court Justices On Getty Images