The conservative attack on abortion rights is expanding, and abortion pills are its next target. After 23 states raised pre-viability (or worse) abortion bans in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, prominent Republicans like Mike Pence are now advocating for nationwide bans on medications like mifepristone and misoprostol that are used to induce abortions. Conservatives at this very moment are using a hand-selected Trump judge from a single Amarillo, Texas court division to try and overrule the FDA’s approval of mifepristone. And more than 20 state attorneys general are threatening litigation against pharmacies like CVS and Walgreens for their continued distribution of the medication.

At the center of these conservatives’ efforts is a push not to pass a new law, but to resurrect a very old one: The Comstock Act, which Congress passed way back in 1873. A long-dead piece of federal legislation, conservatives across the country are attempting to zombify the Comstock Act and use it to attack the national distribution of abortion pills.

The Comstock Act of 1873 was a sweeping anti-obscenity law, restricting all sorts of behavior considered “immoral” by 19th-century Anglo-Saxons. As Vox’s Ian Millhiser has explained, the law is named for its main lobbyist, Anthony Comstock, a New York socialite so caustic that the Supreme Court once aired him out as “a prominent anti-vice crusader who believed that anything remotely touching upon sex was … obscene.” Comstock viewed the government’s authority to impose a nationwide moral code much like he saw his trademark mutton chops: long and vast, with zero thought for what a woman might say about it.

Anthony Comstock in 1913 (Gado / Contributor / Getty Images)

In relevant part, the Comstock Act criminalized mailing or otherwise transporting “every article or thing designed, adapted, or intended for preventing conception or producing abortion.” The law Comstock got passed was broad—so broad, in fact, that courts started limiting its reach from the moment it passed. The Seventh Circuit, for example, in a 1915 case called Bours v. United States basically read a life-of-the-mother exception into the statute. The Bours court acknowledged that “the letter of the statute would cover all acts of abortion” and represented “a national policy of discountenancing abortion as inimical to the national life.” In recognizing this fact, however, the court reasoned that even supporting a policy of “national life” meant carving out scenarios where “an examination shows the necessity of an operation to save life he will operate.”

In a series of cases decided in the 1930s, the Second Circuit expanded on this logic, focusing on a fundamental issue with the Act as written: that taken to its extreme, something “designed, adapted or intended” to prevent pregnancy or produce an abortion could include anything from medical textbooks to Doritos bags. The broadest interpretation of the Comstock Act would thus leave the realm of postal regulation and instead become the total abolition of contraceptives and abortions. The Second Circuit sensibly concluded that this result was “not lightly to be ascribed to Congress,” and instead construed the Comstock Act as “requiring an intent on the part of the sender that the article… be used for illegal contraception or abortion.” The Sixth Circuit in 1933 commended the Second Circuit for “the soundness of its reasoning” and adopted a similar construction. The D.C. Circuit followed suit in 1944.

And for a while, that was that. Hamstrung by those decisions, the government basically stopped trying to enforce the Comstock Act, as detailed in a forthcoming Stanford Law Review article by law professors David Cohen, Greer Donley, and Rachel Rebouche. Outside of a couple amendments in the ensuing decades—most notably removing the phrase “for preventing contraception” after the Supreme Court’s decision in Griswold v. Connecticut—the law reads about the same as it did in 1873. Codified at 18 U.S.C. 1461, the Comstock Act currently bars the Postal Service from mailing anything “designed, adapted,” “advertised” or “intended… for producing abortion.”

In the immediate aftermath of Dobbs, the USPS asked the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) to dive into this case law and see what impact the Comstock Act would have on your ability post-Dobbs to access abortion medication. They reached the same basic conclusion I described earlier: that mailing mifepristone and misoprostol is not illegal under the Comstock Act “where the sender lacks the intent that the recipient of the drugs will use them unlawfully.” Under this logic, drug companies should face no problems from Uncle Sam when shipping abortion meds into states where abortion is broadly legalized.

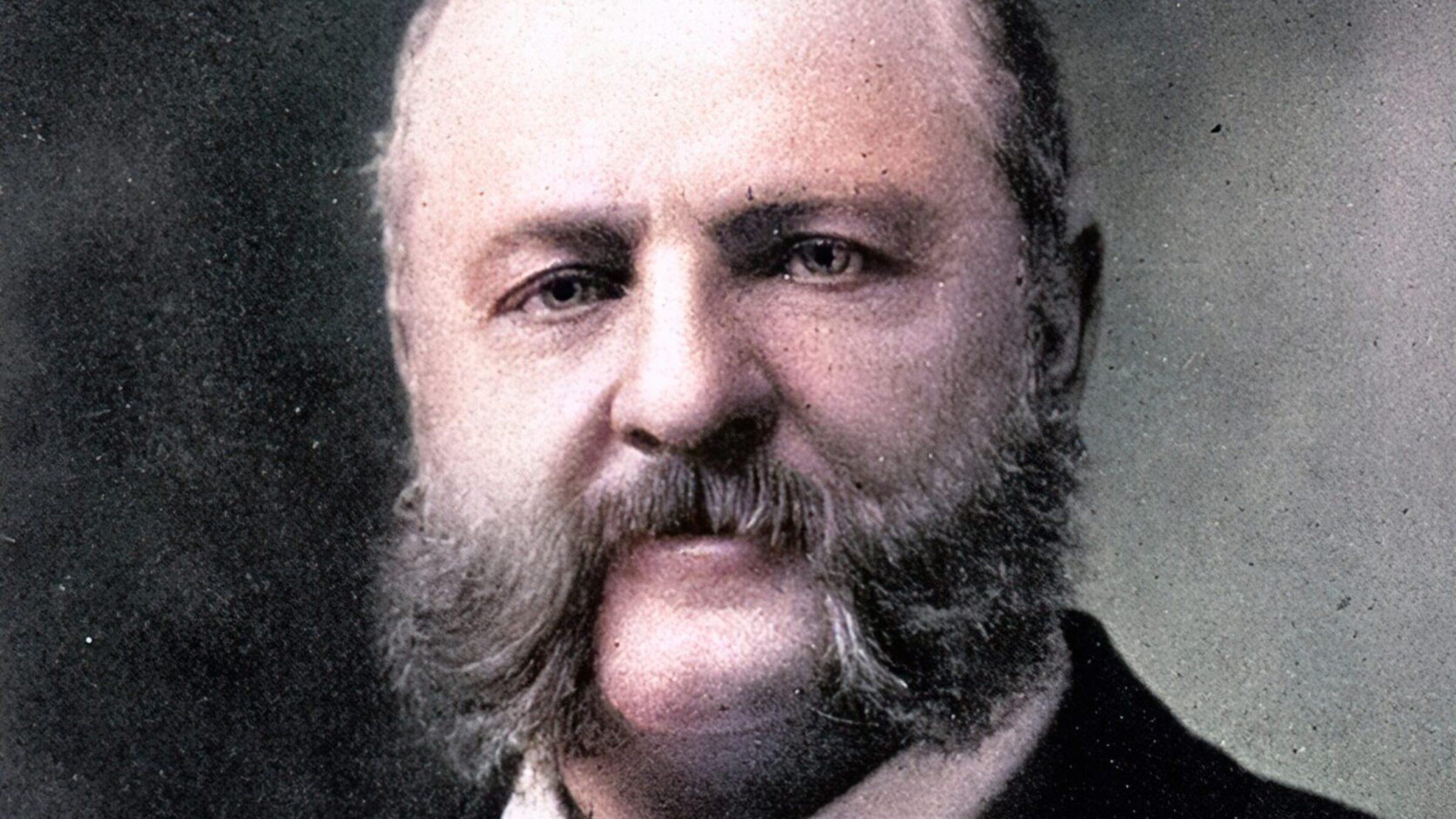

Anthony Comstock today (Photo courtesy Lawyers, Guns, and Money)

But the OLC found this interpretation in practice goes further than it appears on first blush. You see, abortion medications often non-abortion-related uses (like treating miscarriages, or even gastric ulcers in the case of misoprostol), and even states heavily restricting abortion have life-of-the-mother exceptions. Thus, according to the OLC, the simple act of shipping abortion medications—even to a state where abortion is heavily restricted—doesn’t trigger the Comstock Act, because those legitimate use cases mean each state has some population of people who wouldn’t break the law by using these drugs. Just as your grandmother probably never meant for you to use the $20 she mails you for Easter every year on Peep-shaped edibles, proving the sender intended the recipient use the abortion meds to break the law would be nearly impossible. Under the OLC’s interpretation, drug manufacturers and distributors should be able to ship abortion meds to states with near-total abortion bans with little fear of criminal charges.

But of course, that’s not stopping conservatives from corralling their biggest brains to try and resuscitate this crusty statute. In particular, conservative pundit Ed Whelan has been on a blogging bender recently, posting four separate blogs about that OLC report and cobbling them together for an amicus brief he filed in the Texas mifepristone case. Whelan concludes that the OLC’s position has “no meaningful support,” and is just a partisan effort by the Biden admin to render the Comstock Act “a virtual nullity.”

Whelan’s conclusion (which the plaintiffs in the Texas mifepristone case cite in court filings) is that the Comstock Act only permits “use of the postal service for drugs (or other items) when those drugs are being mailed for a purpose other than abortion.” Unlike the OLC’s interpretation, which would allow for the free flow of abortion meds in the mail so long as the drug companies don’t intend the recipient of the drugs violate state law, Whelan thinks the Comstock Act bars shipping abortion drugs for even lawful abortions, full stop. Under Whelan’s theory, even abortion clinics in pro-choice states like California and Washington would be practically cut off from accessing mifepristone and misoprostol.

When neither one nor two nor three blog posts will do (Photo by Scott J. Ferrell/Congressional Quarterly/Getty Images)

Whelan’s argument against the OLC opinion comes in three parts: one, there’s not enough case law to draw a firm conclusion in any one direction; two, those decisions from last century only dealt with contraception and aren’t applicable to the discussion of abortion pills; and three, the OLC intentionally misinterpreted all those decisions, reading the caselaw far too broadly in an attempt “to undermine or circumvent state laws restricting abortion.”

His first point isn’t the worst-faith theory he’s posted online in recent years. By my math, the six appellate cases in the OLC’s report have a grand total of 110 combined citations by other courts in the decades after their issuance. By contrast, Dobbs has already been cited 140 times in the eight months since it dropped. But it’s worth noting that, of the few trial courts given an opportunity to read the appellate decisions and choose a side, the OLC found several (out of Maryland, Arkansas and New York) that reached their conclusion. Whelan, by contrast, can’t cite a single court that’s found the Comstock Act bars the shipment of drugs for the purpose of abortion.

Second, Whelan is correct insofar as every appeals court decision cited by the OLC, save for Bours, involved the regulation of contraception. Where Whelan boofs it again is that, in the context of the Comstock Act at the time, his distinction is basically irrelevant: it prevented the mailing of things “intended for preventing conception or producing abortion.” Why the OLC’s interpretation would apply to the first half of that statement and not the second half, Whelan never coherently explains.

Whelan’s third point is also his most flawed. He argues the case law must be considered within the stringently anti-abortion context of when the Comstock Act was passed. Because abortion was largely illegal in 1873, Whelan thinks the courts cited in the OLC report meant the mailing of abortion meds under the Comstock Act must be largely illegal too. Simple as that, in Whelan’s eyes.

(Photo by Nathan Howard/Getty Images)

Whelan’s trying to do a textualism here, tying the Comstock Act’s restrictions to the cultural hegemony of the 1870s misogynists who enacted this law. Problem is, the OLC’s interpretation of the Comstock Act isn’t based on the tortured reading of statutory language; they just read some case law and applied it to the modern day. So Whelan instead Auntie Annes himself into knots trying to work around the caselaw, and concludes that we are somehow bound by how the Comstock Act applied in 1873 (a comprehensive ban on mailing abortion materials, because most abortions were not “lawful” at the time) and why the drafters of the Comstock Act passed it (to continue the suppression of women’s rights).

This sophistry is hilarious, because it’s the exact opposite logic Whelan would use to scold you about gun rights. The whole conservative meta-narrative behind the Second Amendment is that your right to keep and bear arms exists independently of the Founders’ reason for creating that right—in support of a “well-regulated militia,” as the Second Amendment scrupulously notes. That principle applies here, too. The nation’s perception of a “lawful” use for contraceptives or mifepristone has changed over time (just like what constitutes “arms” isn’t just muskets anymore), but that doesn’t mean the Comstock Act’s prohibitions have. For a guy who thinks the court’s role is limited to saying what the law means, he has no problem deferring to the opinions of 1870s senators with unwashed asses when it suits his policy preferences.

The longstanding judicial interpretation of the Comstock Act is that the federal government can’t use the Postal Service to further restrict contraception and abortion. That states began broadening access to abortion is not evidence that a century of precedent is flawed, but is instead an straightforward illustration of that federalism thing you learned about in your AP U.S. History class.

The Texas mifepristone case is just the beginning of the conservative movement’s revitalized efforts to ban abortion nationwide. Congressional Republicans are too chickenshit to propose the sweeping new abortion restrictions they want, knowing full well the voting public is not on their side. So instead, conservatives are hoping their lackies in the courts will overturn decades of uncontroversial precedent and handle business for them. If Dobbs is any indication, they might get their wish.