There are many things to hate about the draft materials from President Joe Biden’s blue-ribbon commission on Supreme Court reform, which seems to lack both the ambition and the capacity to meaningfully answer critical questions about the Court’s waning legitimacy. But the commission didn’t just botch big ticket-reform items like, for example, adding seats to the Court. It also absolutely tanked a less high-profile issue: the Court’s leading role in helping the government put people to death.

The draft materials’ discussion of the Court’s treatment of death penalty cases appears in a weirdly sprawling grab bag of a section entitled “Case Selection and Review.” In it, the commission covers the Court’s dubious uses of its emergency “shadow docket”; expresses concern over the minuscule number of attorneys who appear before the Court; frets about the justices’ workload; and ponders whether the Court needs a functioning, enforceable code of ethics, which is somehow not something that it already has after more than 200 years of existence.

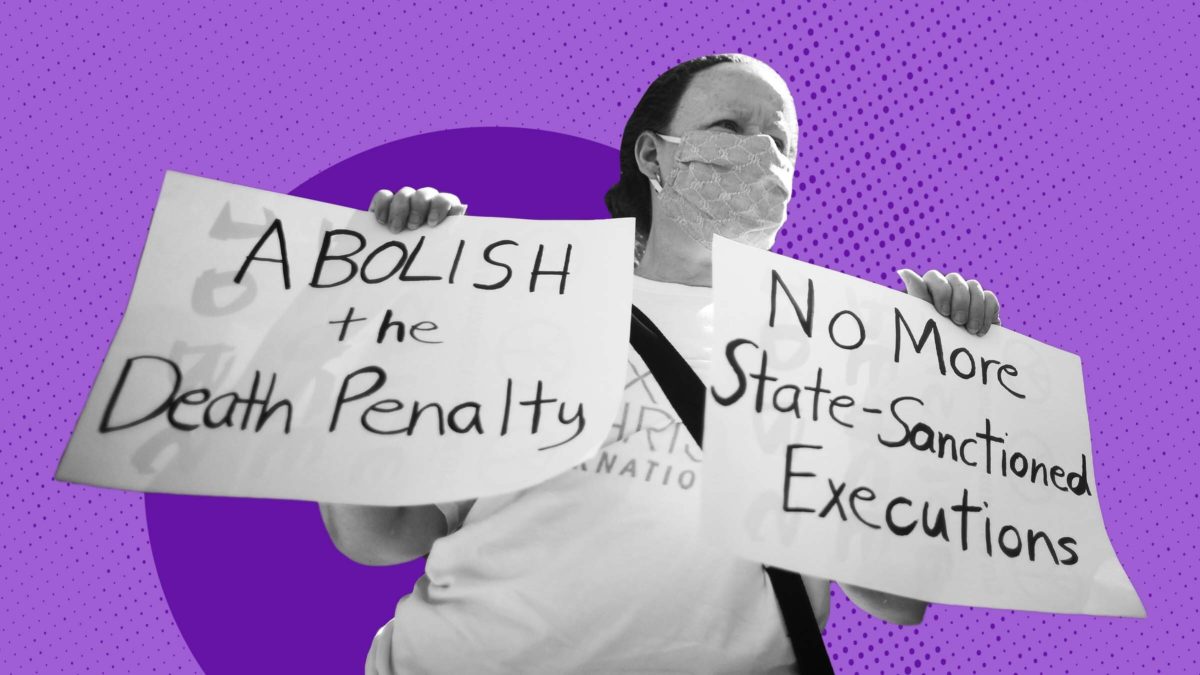

Wedged in the middle appears a series of execrable both-sides takes on how the Court is handling the death penalty, a wildly racist form of punishment that half of states have abandoned or outright abolished. This issue is especially relevant for the Court reform conversation after President Donald Trump went on what Justice Sonia Sotomayor called an “expedited spree of executions” at the end of his tenure, ordering his Department of Justice to proceed with the executions of 13 people between July 2020 and Inauguration Day 2021—the first federal executions since 2003.

On one side of the ledger, the commission’s review of the Court’s death penalty jurisprudence acknowledges that “death is different”—that the state really can’t unring the proverbial bell if it puts an innocent person to death. As Innocence Project executive director Christina Swarns put it in her testimony before the commission, there “is no area of the law in which reliability, accuracy, and fairness are more critical than capital punishment.” At least 185 people have been wrongly convicted of a capital crime in the United States, only to be exonerated much later.

However, the notion that the Court might be the final link in a chain of decisions that results in an innocent person’s death does not seem to cause much consternation for the commission. Instead, it stacks up that possibility against the simple fact that conservatives like Justice Clarence Thomas want people to be put to death much more swiftly, quoting his gripe from 2019 that granting eleventh-hour stays of execution “rewards gamesmanship.” The framing of the last desperate acts of people who don’t want the state to kill them as “gamesmanship” is the ultimate expression of disdain for the life of the person facing death. Even the most milquetoast of the Court’s liberals, Justice Stephen Breyer, has expressed outrage at this rush to punish: “What are courts to do when faced with legal questions of this kind? Are they simply to ignore them? Or are they, as in this case, to ‘hurry up, hurry up’?” he wrote in January, protesting the Court’s decision to greenlight the execution of Dustin Higgs. “That is no solution.”

Another point the commission makes in defense of the Court’s death penalty jurisprudence: Executions are typically authorized via warrant, and if a stay causes those warrants to expire, the government needs to get a new one. How long can that delay things? Per the commission, “a month or more.” If preventing the government from executing possibly-innocent people feels more important than maintaining an on-time execution schedule, congratulations, you have figured out how to display a bare modicum of humanity in a way that the commissioners evidently did not.

The commission couldn’t even fully get behind the simplest procedural fix suggested by some witnesses: an automatic stay, which would require the Court to postpone executions until defendants exhaust certain types of appeals the law affords them. The commission sets this modest, eminently reasonable step, however, against the testimony of conservative appeals lawyer Hashim Mooppan, who told the commission that such a rule would put an “unwarranted thumb on the scale in favor of capital inmates.” This is, again, ludicrous. On one side of the scale, you have a person about to be put to death; on the other, the entire weight of the American legal system and a Court dominated by people who are fine with capital punishment. To mix a metaphor, putting a thumb on the scale here would barely move the needle.

Another approach the Commission explored: granting stays of execution when four justices, rather than the five, agree to do so. (This rule would parallel the four-justice threshold necessary to grant certiorari for cases on the merits docket.) The commission just as quickly dismisses this proposal, though, after citing former Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s fears that four justices might “frustrate the effectuation of the will of the majority” by voting as a bloc. As a witness pointed out, both real-life experience and practical considerations make this outcome not especially likely. And in the context of the Court’s 6-3 supermajority, the irony of complaining about a rule that would “frustrate the effectuation of the will of the majority” is almost too much to bear.

In some ways, the chaos here parallels Biden’s often-contradictory stance on capital punishment: He campaigned on ending the death penalty, but hasn’t pushed for legislation to that effect since taking office. His Department of Justice dropped capital charges in seven pending criminal cases, but also really wants to put the perpetrator of the Boston Marathon bombing to death. Absent a clear stance on the issue from the president, it’s probably not a surprise that the country’s other elite institutions are following suit.

This portion of the commission’s work is a perfect encapsulation of why an exercise like the commission was always doomed to fail: There’s no moral principle on display here, just a series of academic musings presented as equally compelling ideas that must be accorded equal weight. A considerable number of the most powerful people in the legal system apparently believe that people sentenced to death in this country are treated far, far too fairly.

Today’s Court is 27 years out from Justice Harry Blackmun’s impassioned explanation for why he was giving up on capital punishment. “From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death,” he wrote. “Rather than continue to coddle the Court’s delusion that the desired level of fairness has been achieved and the need for regulation eviscerated, I feel morally and intellectually obligated simply to concede that the death penalty experiment has failed.” For the commission, this failure is still not serious enough for them to even suggest doing anything about it.