Over the last few months, several high-profile organizations and individuals have announced their support for adding seats to the Supreme Court—in some cases, after long opposing it. Many of them had to re-examine long-held assumptions in order to do so. Some had to accept the possibility of negative repercussions for going public.

Yet they all reached the bracing conclusion: Whatever reservations they once had are outweighed by the crisis for regular people and democracy if the Court remains on its current path.

Nan Aron, the since-retired president of the Alliance for Justice, told Biden’s Supreme Court reform commission last year that the Court has so tarnished its own legitimacy that “reform is in fact necessary to restore legitimacy to the Court.” In its own letter to the commission, the Service Employees International Union called for reform to ensure the Court “provides justice for all, not just the privileged few.” In The Washington Post, commission members Nancy Gertner and Lawrence Tribe noted that they had previously opposed Court expansion, but had since changed their minds. In TIME magazine, their fellow commissioner Kermit Roosevelt wrote that expansion “may be the only thing that will save our democracy for the next generation.”

Lawmakers are also speaking out. In December, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren published a Boston Globe op-ed announcing her support for the Judiciary Act of 2021, a bill introduced by Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey and Reps. Jerrold Nadler, Hank Johnson, and Mondaire Jones that would add four seats to the Court. The 98-member Congressional Progressive Caucus, meanwhile, endorsed the Judiciary Act in January. Expansion has moved from an obscure law-nerd topic to a front-and-center issue for Democratic politicians and activists.

All of these groups and people are institutionally dependent on the Court, or, at the very least, face pressures that might have otherwise prompted them to remain quiet. Gertner, Roosevelt, and Tribe, for example, are law professors whose professional success is measured partly by their ability to place students in Supreme Court clerkships. SEIU is frequently a party before the federal courts, while Warren is part of a bare Democratic Senate majority and has an incentive to avoid upsetting that precariously balanced boat. More generally, liberals and progressives tend to see themselves as defenders of institutions in the face of efforts by the right to tear them down. Supporting a significant change to the Court requires overcoming that inclination to preserve the status quo.

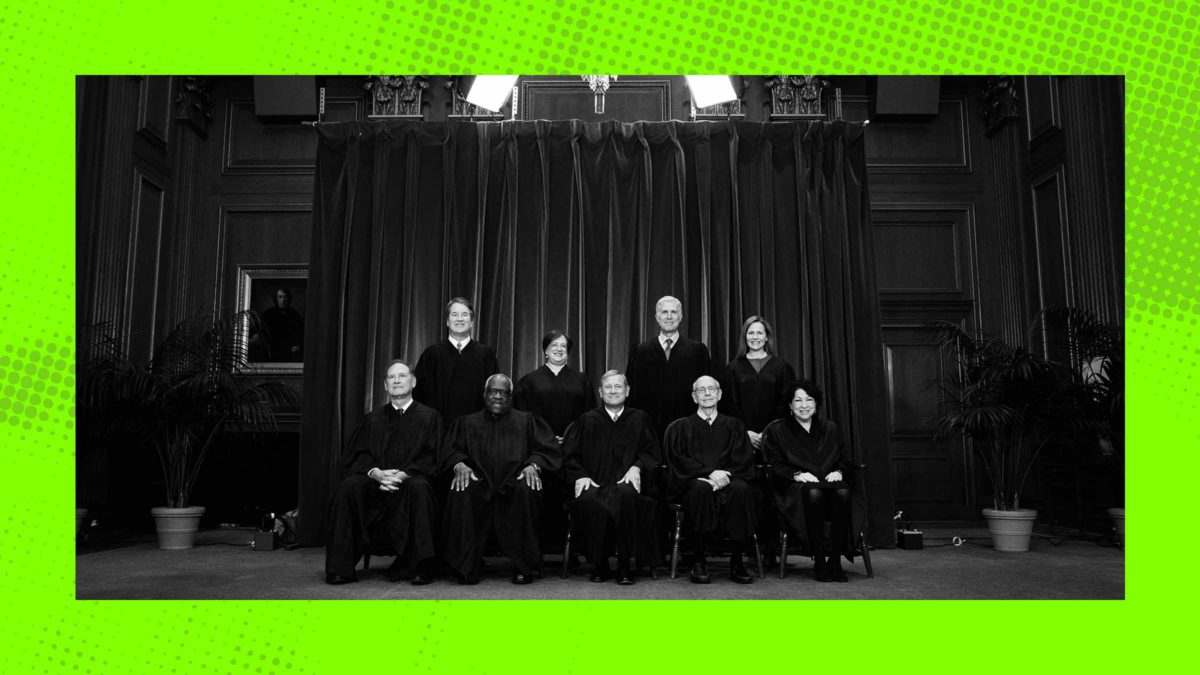

Pictured L-R: Partisan hack; partisan hack (Photo by SUSAN WALSH/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

Criticizing the Court also invariably invites one or more of its members to lash out. In a speech last September at the McConnell Center at the University of Louisville, accompanied by the real-life Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, Justice Amy Coney Barrett mind-blowingly argued that she and her colleagues are not “a bunch of partisan hacks.” A few weeks later, Justice Samuel Alito gave a fiery speech attacking his critics, including journalist Adam Serwer, for having the audacity to point out the Court’s use of its “shadow docket” to dramatically change the law without hearing arguments or writing full opinions. Those who are nonetheless speaking out about Court expansion decided that the harms of the Court’s decisions are more consequential than becoming the object of indignation of whichever conservative justice gives a speech next.

The new reformers’ statements echo the bleak theme that the Court has become a partisan entity that, as Warren put it, “threatens the democratic foundations of our nation.” Gertner and Tribe sounded a similar note of alarm when they described the Court as “on a one-way trip from a defective but still hopeful democracy toward a system in which the few corruptly govern the many.”

The expansion supporters identify three sources of this dynamic: First, what Gertner and Tribe called the “dubious legitimacy” of the appointments of Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Barrett that resulted in this 6-3 conservative supermajority. As Aron pointed out, a Republican presidential candidate has won the popular vote once since 1992, but Republican presidents have appointed two-thirds of the current Court.

Second is the Court’s jettisoning of supposed rules and norms in favor of rankly partisan behavior—or, as the SEIU put it, a failure to “consistently adhere to a judicial philosophy, to precedent, or to true facts.” Gertner and Tribe referred to Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s description that the “stench” of politics that permeates recent Court decisions that have handed victory to the GOP issues like abortion, voting rights, and COVID-19 restrictions.

“This is a problem of partisan politics. It is the Republican Party attacking democracy, and the Supreme Court is helping it.”

The third, and most fundamental, problem is the Court’s decisions that consistently harm people and democracy. The justice have made it harder for people to form unions, to sue corporations in court, to obtain health insurance, to control their reproductive futures, to fight discrimination at work, and to hold the police accountable for racist misconduct and violence. They have gutted the Voting Rights Act and blessed voter suppression, partisan and racial gerrymandering, and unlimited dark money, all with the effect of entrenching minority rule. “This is a problem of partisan politics,” Roosevelt wrote. “It is the Republican Party attacking democracy, and the Supreme Court is helping it.”

For many of these critics, support for Court expansion did not come easily. Aron explained that she had long worried that it would politicize the institution and “lead to an untenable arms race.” But, she said, she “the reality of our current crisis” leaves her no other choice. Gertner and Tribe similarly opined that “hand-wringing over the court’s legitimacy misses a larger issue: the legitimacy of what our union is becoming.” Roosevelt put it most bluntly: “I have always viewed expansion with great skepticism, as a last resort, the fire axe in the glass case on the wall,” he said. “But we may well be at the point of breaking that glass now.”

For many lawyers, backing real Court reform requires a painful re-examination of foundational assumptions of legal culture: that the law has some internal consistency, and that judges are generally constrained by rules, norms, and their consciences to respect the rule of law. It is difficult to spend decades of your life as a lawyer without having some belief—or at least hope—that these rules and norms mean something.

But the rapid pace at which the Court’s conservative supermajority is undoing decades of precedent to entrench Republican policy preferences has a funny way of putting those hopes into perspective. The liberal tendency to believe in institutions cannot be stronger than direct evidence that an institution has become a danger to our country. There is a reason the fire axe is waiting in that glass case: When there’s a fire, you’re supposed to break it.