According to an explosive investigation by the New York Times, Justice Samuel Alito or his wife allegedly leaked the 2014 Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores decision, which limited access to contraceptives, to conservative Christian donors weeks before the opinion was published. Whistleblower Rob Schenck, an evangelical minister and former anti-abortion activist, alleged that donor Gayle Wright told him that she found out that Alito would write a majority opinion in favor of Hobby Lobby over dinner with the Alitos. Schenck said he then used that information to prepare a celebratory publicity plan. (Both Alito and Wright denied the account.)

Schenck also described the mechanics of a sophisticated influence operation, for which he would advise wealthy conservative activists like Wright to contribute money to the Supreme Court Historical Society, make friends with justices at its functions, and invite them to private clubs, vacation homes, and dinners. (In his statement of denial, Alito said that he and his wife became “acquainted with the Wrights some years ago because of their strong support for the Supreme Court Historical Society, and since then, we have had a casual and purely social relationship.”) Schenck’s account, if true, pulled back the curtain on an influence peddling network between rightwing Christian megadonors and the highest arbiters of justice in the country.

That the Supreme Court may now be under sway of a well-oiled machine of ultra-wealthy evangelical extremists is no secret. In his new book American Crusade: How the Supreme Court Is Weaponizing Religious Freedom, First Amendment lawyer Andrew Seidel argues that the First Amendment has been used by the conservative Christian movement to impose their religion on others. Examining key cases over the past 30 years, he outlines a pattern of conservative Christians carving out privileged exemptions for themselves. One of the key tools for doing so was the 1993 Religious Freedom and Restoration Act (RFRA), which was passed in response to the lack of protections for Native spirituality.

The background for the RFRA goes like this: In 1990, Al Smith, a member of the Klamath tribe, challenged Oregon’s denial of unemployment benefits after he was fired for using peyote during a religious ceremony. After Smith, who worked as a counselor at a drug rehabilitation nonprofit, received an invitation to a religious ceremony, he informed his boss of his plans to participate in a ritual ingesting peyote, which he believed also aided his recovery as an alcoholic. His boss subsequently fired him for violating the nonprofit’s prohibition of illicit drug use.

When an individual is fired for violating a workplace policy, as Smith was, they are ineligible for unemployment benefits. Smith applied for those benefits anyway, and when he was denied, he took his case to the Supreme Court, arguing that the denial violated his First Amendment right to religious expression free of government interference. In Employment Division v. Smith, a 1990 decision written by Justice Antonin Scalia, the Court ruled against Smith, explaining that Oregon criminal law prohibited all peyote use and just because Smith’s illegal behavior was “accompanied by religious convictions” didn’t mean it wasn’t “prohibitable conduct.” Smith’s employer was within its rights to fire him, the Court held, and so was the state of Oregon when it denied him unemployment benefits.

Three years later, Utah Representative Karen Shepard, a co-sponsor of the RFRA, and Texas Representative Jack Brooks invoked Scalia’s opinion with disdain while advocating for the law’s passage in the House. “A single Supreme Court decision abolished the standard that protects religious freedom in this country,” Shepard said; the decision “transformed a hallowed liberty into a mundane concept with little more status than a fishing license,” added Brooks. When then-Senator Joe Biden introduced the bill on the Senate floor, he claimed that the Smith decision, if allowed to stand, “will erode religious freedom.” The law passed in 1993.

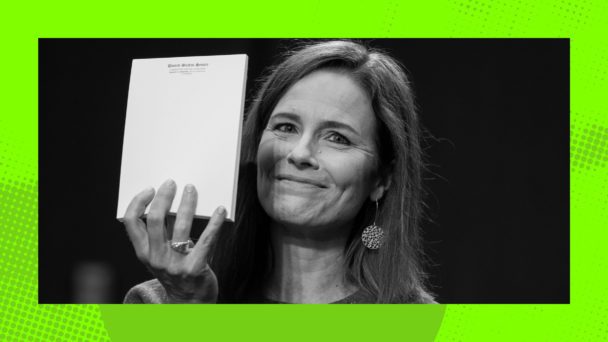

When someone asks if you leaked the result of a key First Amendment case to sympathetic rich people (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

But the RFRA may have been superfluous when there was a simpler fix readily available. At the time of the RFRA’s passing, Native people’s religious worship was theoretically already protected by the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act. If Congress’ motivation for passing the RFRA was rectifying the consequences of Smith, the most direct solution would have been to include peyote use as a protected activity under that law—which it did in 1994. While Smith might have provided rhetorical fodder for opportunistic politicians, neither law translated to increased protections for Native people.

But the passage of the RFRA proved to be a windfall for Christian nationalist groups. Seidel identifies a coalition of right-wing religious zealots who supported the passage of the law and later advocated for state-level versions of it, including the Alliance for Defending Freedom, the Family Research Council, and First Liberty Institute, which are allied with James Dobson, an anti-gay evangelical broadcaster. The network also includes Ann and Neil Corkery, who helped found the Judicial Crisis Network, a group that promotes the confirmation of conservative Christian judges to the federal bench.

The Hobby Lobby decision came in response to a request from the owners of the crafts chain, who asked the Court to exempt them from paying for employee reproductive healthcare on religious grounds, citing the RFRA, and won. Seidel points out that the company’s retirement plan invested $73 million in drug companies that manufacture intrauterine birth control devices, emergency contraceptive pills, and drugs used for abortion—a corporate strategy that seemed to undercut their argument that it was only sincere religious conviction that motivated Hobby Lobby executives to seek such an exemption. Nevertheless, the Court held that providing reproductive healthcare for its employees was a “substantial burden” on the owners’ religious beliefs.

These considerable gains for Christians stand in contrast to the dismissal of Native people’s religious claims in federal courts. In 2009, the Court, without explanation or comment, denied the Navajo Nation’s appeal of a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decision allowing recycled wastewater to run through San Francisco Peaks, thereby desecrating a mountain range considered sacred to the Nation. “The presence of recycled wastewater on the Peaks does not coerce the Plaintiffs to act contrary to their religious beliefs,” the Ninth Circuit held.

In 2016, the Cheyenne River Sioux Nation, emboldened by the Hobby Lobby decision from two years earlier, brought a challenge to the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline near the Missouri River. They argued that the pollution of the river, which they held as sacred, would violate their religious expression. But a federal judge held that the tribe hadn’t demonstrated a “substantial burden” on its worship, and had “inexcusably delayed” voicing its RFRA objection.

The most that Native people have gained under RFRA is a ‘not guilty’ verdict. In January, a federal judge declared Amber Ortega not guilty of criminal charges stemming from interfering with the construction of a border wall near Quitobaquito Springs, a body of water considered sacred to the Hia C-ed O’odham Nation. Ortega lodged a successful RFRA-based defense to the charges, claiming the government’s prosecution placed a substantial burden on her exercise of religion. The decision stands as an outlier amongst dismissals of Native people’s RFRA-based claims.

Hobby Lobby President Steve Green and his wife Jackie Green speak at Stork Ball 2020 at the Ronald Reagan Building in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Leigh Vogel/Getty Images for Save The Storks)

That Christian nationalists gained privileges on the back of Smith and his legal fight is part of a longer history of displacing Native cultures and religious beliefs for white Christians. Smith, for example, survived abusive Catholic and Christian boarding schools where staff had the explicit mission of eradicating Native religious and cultural practices. The teachers at St. Mary’s, the first of such schools that Smith attended as a 7-year-old, “made sure he did not learn his own language, the history of his people, or the rituals that Klamaths had used to mark the seasons for more than ten thousand years,” wrote law professor Garrett Epps in a book chronicling Smith’s life. When Smith attempted to run away from the forced indoctrination, priests beat him with a leather strap.

More than 150,000 Native children attended boarding schools like the one Smith went to—all dedicated to stamping out Native languages and cultures. It wasn’t just a handful of boarding schools dedicated to the project of erasure, either: In the nineteenth century, an agent of the Bureau of Indian Affairs forced “American” names onto everyone in the Klamath tribe of Southern Oregon. Al Smith died not knowing his true name.

For centuries, the U.S. government has enacted violence on and degraded indigenous people, including through theft of land, forcible family separations, and the genocide of millions. In 1993, Congress ostensibly passed the RFRA to reverse course and offer protection for Native religions. But the Court still remains unwilling to protect Native spirituality—while stretching it again and again for Christians. There is no network of powerful Native megadonors making sizable contributions to the Supreme Court Historical Society, inviting the Alitos over for dinner, and drawing up lists for Supreme Court nominations. Perhaps justice would be on their side if that were the case.