Last month, the former Speaker of the Minnesota House of Representatives, Melissa Hortman, was assassinated in her home, along with her husband, Mark. Minnesota State Senator John Hoffman and his wife Yvette were shot multiple times by the same attacker. The shooter had a list of additional targets, and went to the homes of multiple legislators who appear to have been saved only by virtue of being out of town. These attacks follow other recent high-profile incidents of political violence: an arson attack on the home of Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro; two apparent attempts to assassinate Donald Trump; and the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, in which a mob of Trump supporters attempted to find and kill members of Congress who refused to reimagine the election results in his favor.

The dangers have not been limited to elected officials. Approximately one-third of federal judges have been subjected to threats in just this fiscal year, according to data compiled by the U.S. Marshals Service. In 2020, Daniel Anderl, the son of Judge Esther Salas of the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey, was murdered by a lawyer who had appeared in Judge Salas’s courtroom, and who appeared to have targeted the judge as part of an anti-feminist vendetta. In recent months, other federal judges have been sent pizzas under the name of Salas’s son, which they’ve interpreted to be both a message that people know where the judges live and a threat of violence.

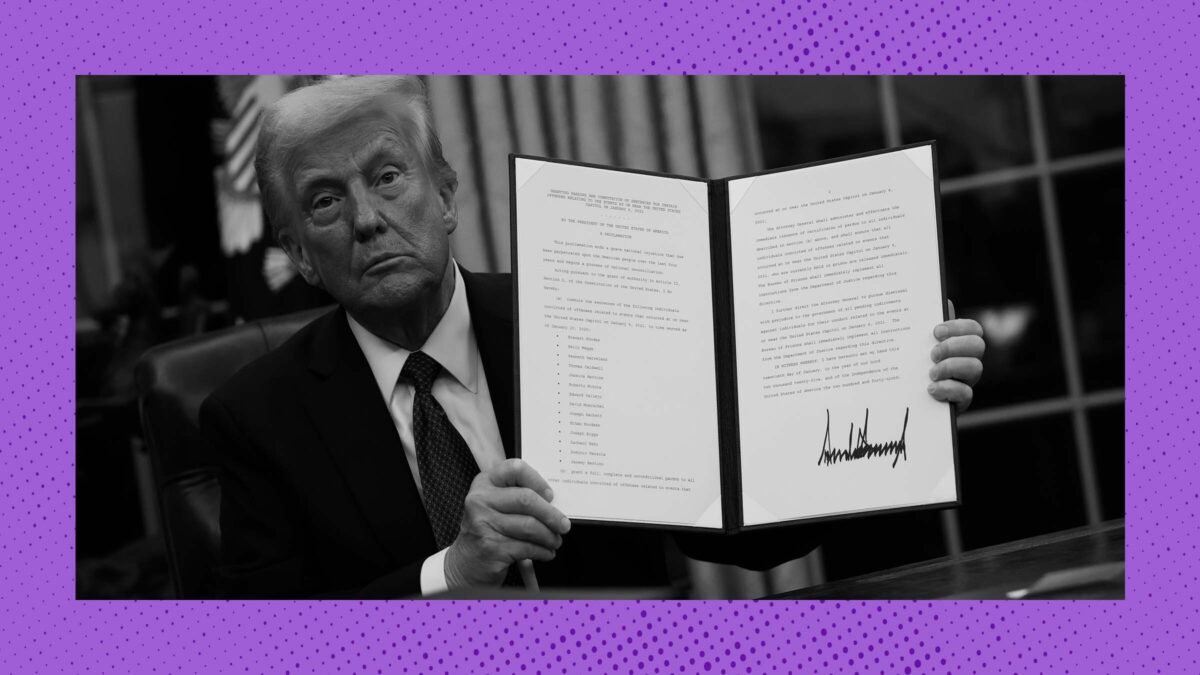

As Johns Hopkins political scientist Lilliana Mason explains, one of the best ways to decrease political violence is for public officials to set an example—to avoid violent, dehumanizing rhetoric that signals that physical violence might be acceptable. Unfortunately, the current President of the United States is Donald Trump, who exhorted the January 6 rioters to “fight like hell,” and issued them pardons for criminal convictions after his reelection in 2024. During his first term, Trump frequently used the violent, dehumanizing language that Mason warns against in reference to judges specifically. He said that an Indiana-born judge could not be impartial because he was “Mexican”; argued that rulings by “Obama judges” were making the country unsafe; and generally implied that any judges who didn’t support his attempts to consolidate power and enact a far-right agenda were the enemy.

This trend has continued in his second term. Trump has called Judge James Boasberg, who temporarily blocked the administration from deporting noncitizens to El Salvador, a “radical left lunatic,” and called for his impeachment. Trump’s former-top-advisor-turned-social-media-enemy Elon Musk has gone after judges who have attempted to slow Trump’s assault on the Constitution, including Judge Amir Ali of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, who ordered the administration to release congressionally-allocated funding for the U.S. Agency for International Development. Other Trump advisors have accused judges of engaging in “judicial tyranny” and abusing their power for having the gall to stop Trump from breaking the law whenever he feels like it.

One strange legal situation that makes Trump and his allies’ attacks on federal judges even more troubling than his attacks on others whom he sees as challenging his authority is the fact that Trump himself is ultimately responsible for federal judges’ safety. This is because the U.S. Marshals Service, the federal agency tasked with providing security to the federal judiciary, does not report to the federal judiciary. The agency is controlled by the executive branch and reports to Attorney General Pam Bondi, raising the concern that Trump could order them to stop protecting certain (or all) judges.

In response to this risk, Democrats in both the House and Senate have introduced the Maintaining Authority and Restoring Security to Halt the Abuse of Law (MARSHALS) Act, which would move oversight of the U.S. Marshals Service to the judiciary—specifically, to the Chief Justice of the United States, John Roberts, and the U.S. Judicial Conference, the body that sets policy for how federal courts will operate. In the words of Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey, the legislation is needed because the Marshals’ “dual accountability to the executive branch and the judicial branch paves the way toward a constitutional crisis.”

This legislation is, quite obviously, a good idea, and something that would have been good to do back when there was a president in office who opposed political violence. Unfortunately, the likelihood of the current occupant of the White House signing a bill that decreases his power—and, thus, his ability to instill fear in those he perceives as his political enemies—seems low, to say the least.

But the president’s unwillingness to protect members of a co-equal branch of government does not mean that Congress has to go along with it. Over the last two months, the Supreme Court, which is controlled by a six-justice conservative supermajority, sided with the Trump administration in nearly 94 percent of cases in which the administration was a party. But the lower courts, and particularly the federal district courts, have proven more willing to hold Trump accountable for his attacks on the rule of law. During the same period, the administration lost over 94 percent of the time in district court and nearly 70 percent of the time in the circuit courts. The lower courts have been among the most important parts of the resistance to authoritarianism of the first five months of Trump’s second term.

Our collective ability to defend against democratic backsliding will depend on both institutional and noninstitutional checks on the president, and the courts are a crucial part of that effort. To the extent that any Republican lawmakers still believe they have responsibilities other than ceding as much power to Trump as he asks for, supporting this legislation seems like a reasonable ask in a democratic society.

Trump knows this—it’s part of what caused him to move quickly to target lawyers at big firms this time around. And while he might not be able to target judges in precisely the same way, he can raise the temperature in the environment in which they’re operating. Lawmakers need to ensure that judges don’t have to choose between doing their jobs and risking their safety and that of their families. Taking control of their security out of Trump’s hands, ensuring that upholding the law doesn’t require extraordinary levels of bravery, is a good place to start.