Back in 2023, the Supreme Court issued its first-ever code of conduct for the justices, at last tacitly acknowledging that the institution’s inability to impose consequences for its members’ various ethical indiscretions is, to use a legal term of art, not a great look. In an obnoxious-even-by-Surpeme-Court-standards preface, the justices insisted that the code was “not new,” and that they intended it only to correct the persistent “misunderstanding” that they “regard themselves as unrestricted by any ethics rules.” In other words: Are you happy now? We wrote something down on letterhead and everything!

Unfortunately for the justices, this glorified PR stunt was not as effective as they hoped: Observers quickly noted that the code, among other problems, conspicuously contains exactly zero enforcement provisions, which sort of obviates the point of having a “code of conduct” in the first place. To take a purely hypothetical example, if Clarence Thomas were to conceal his next billionaire-financed megayacht vacation in flagrant violation of the putative rules, and the only possible punishment were (still) impeachment by the Republican-controlled House and conviction by a two-thirds majority of the Republican-controlled Senate, the problems posed by an unaccountable superlegislature whose members enjoy life tenure are no less glaring than they were the day before the code was published.

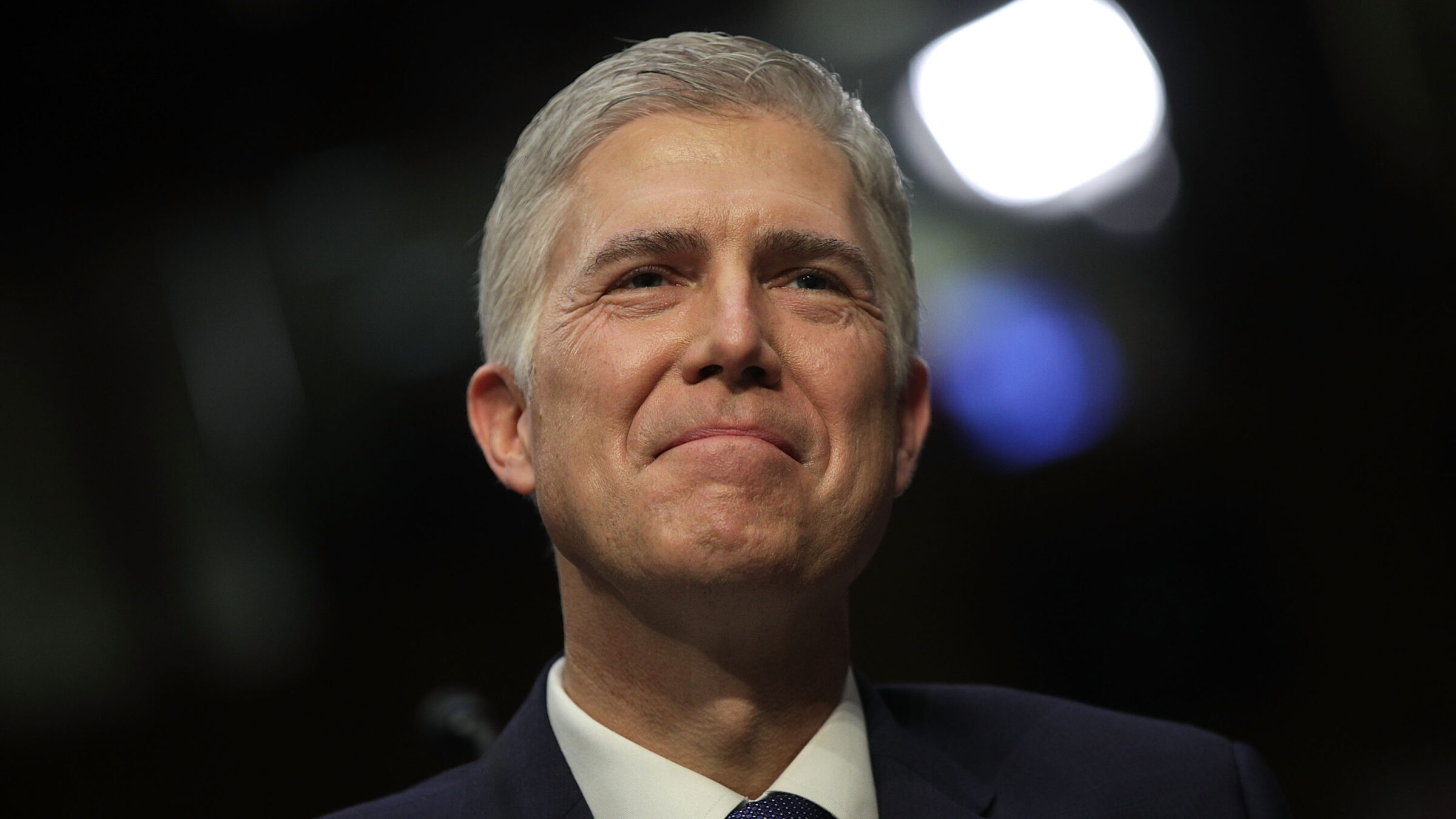

According to a recent report in The New York Times, the reason the code does not include an enforcement mechanism is that—and I do not mean to shock you here—the conservative justices really, really didn’t want one. As the justices negotiated amongst themselves, write Jodi Kantor and Abbie VanSickle, Neil Gorsuch was “especially vocal” in opposing anything beyond “voluntary compliance.” One of Gorsuch’s internal memos that raised “questions and cautions” about the code’s proposals apparently exceeded 10 pages, which is roughly 9.5 pages more of Neil Gorsuch’s tedious, plodding writing than anyone should have to tolerate.

(Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

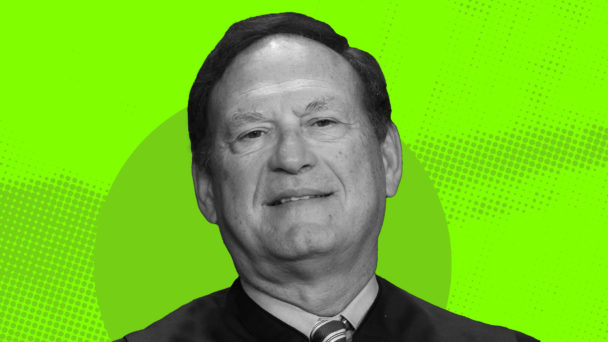

In the same vein, the Times reports that Thomas and Justice Samuel Alito—the two justices whose conduct is probably more responsible than anything outside of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization for mounting public distrust in the Court—were similarly skeptical of the effort, dismissing critics as “politically motivated and unappeasable.” Gorsuch wanted the appearance of officious-sounding rules without any attendant obligations; these two saw no need to bother with appearances in the first place.

The argument attributed to Thomas and Alito here is pretty common in conservative circles, and basically holds that any and all calls for Supreme Court “ethics reform” are barely-disguised attacks designed to discredit the Court, invariably leveled by people who do not agree with the substance of its decisions. “If they can’t get their way on the merits, they go after the Court itself,” said Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell in 2023. That same year, Republican Senator Lindsey Graham excoriated contemporaneous reporting on Thomas’s financial improprieties as “an unseemly effort by the Democratic left to destroy the legitimacy of the Roberts Court.”

The Wall Street Journal editorial board, an entity whose continued existence proves that talentless writers will always be able to find work in journalism as long as their politics are sufficiently reactionary, once bemoaned the push for Supreme Court ethics reform as “an attempt to intimidate and control the Justices by other means,” and a “betrayal of the Constitution that would destroy judicial independence.”

I concede that I will not have fewer objections to Sam Alito’s jurisprudence of Christian nationalism if marginally more robust ethics rules required him to fill out another form at the end of each tax year. But the thuddingly obvious fact that these arguments ignore is that even if you do not, like me, think the Court is bad, and even if you are not with me on the need for Democrats to give Alito between 10 and 300 new colleagues at their earliest opportunity, it is perfectly reasonable to be neutral toward (or even supportive of!) this Court’s policy agenda and still want some assurances that its justices—public officials who are ostensibly committed to upholding the rule of law in a nonpartisan manner—aren’t living in some billionaire’s breast pocket. A 2023 Politico/Morning Consult poll found that fully 75 percent of voters want a binding Supreme Court ethics code: 81 percent of Democrats, sure, but also 70 percent of Republicans.

Conservative justices and/or pundits who hand-wave away calls for ethics reform are never making a serious argument about the need to maintain the Court’s independence. They are simply trying to protect the Republican Party’s most important source of political power, and using the Court’s independence as a shield against the imposition of any form of accountability.

(Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Not everyone on the Court is satisfied with the status quo. As Kantor and VanSickle note, since the code debuted in 2023, Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson have continued to argue for making it enforceable, sometimes politely and sometimes with barely-contained annoyance. “Rules usually have enforcement mechanisms attached to them,” Kagan said in July. “This set of rules does not.”

The liberal justices’ challenge, now as ever, is that they simply do not have the votes to make it so. In theory, Congress could do the work of imposing an ethics code on the justices by passing legislation. In practice, the Republicans who control both chambers of Congress are not going to do anything that would upset the Republicans who control the Court across the street.

After Democrats won the House, the Senate, and the White House in 2020, they had a real opportunity to enact meaningful Supreme Court reform—or at least, given how narrow their Senate majority was, to put Court reform at the top of their agenda, building public support for reforms that a future, larger Democratic Senate majority might be able to pass. For the most part, they squandered it: No ethics legislation even made it past the Senate floor, and President Joe Biden did not publicly endorse the idea until a few days after he dropped out of the 2024 presidential race. As a result, we are stuck for the foreseeable future with the only variety of Supreme Court “ethics code” that this six-justice conservative supermajority agreed to tolerate: one that doesn’t require them to do a single blessed thing they don’t feel like doing.