The pernicious myth that Chief Justice John Roberts is a moderate conservative may finally be put to rest. Over the weekend, the Times reported that behind the scenes, Roberts quickly took hardline stances in cases related to the January 6 insurrection, pushing for outcomes most favorable to Donald Trump. Some court-watchers’ suspicions that Roberts was a Never-Trump Republican were, as it turns out, greatly exaggerated.

Perhaps less surprising than the revelations in the reporting were the Times’s sources inside the famously opaque Court: “the justices’ private memos, documentation of proceedings and interviews with court insiders, both conservative and liberal, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because deliberations are supposed to be kept secret.”

Conservative commentators, as they usually do, raced to condemn not the embarrassing substance but the tainted process. The Wall Street Journal editorial board called the leak a “betrayal of confidence” that is “damaging to the comity of the Court.” Fox News commentator John Shu mourned violations of the “sacred confidentiality” of the decision-making process: “It’s really scary that yet another norm has been shattered,” he said. And David Harsanyi wrote in the Washington Examiner that whoever leaked the internal documents is “part of a conspiracy to destroy the Supreme Court.”

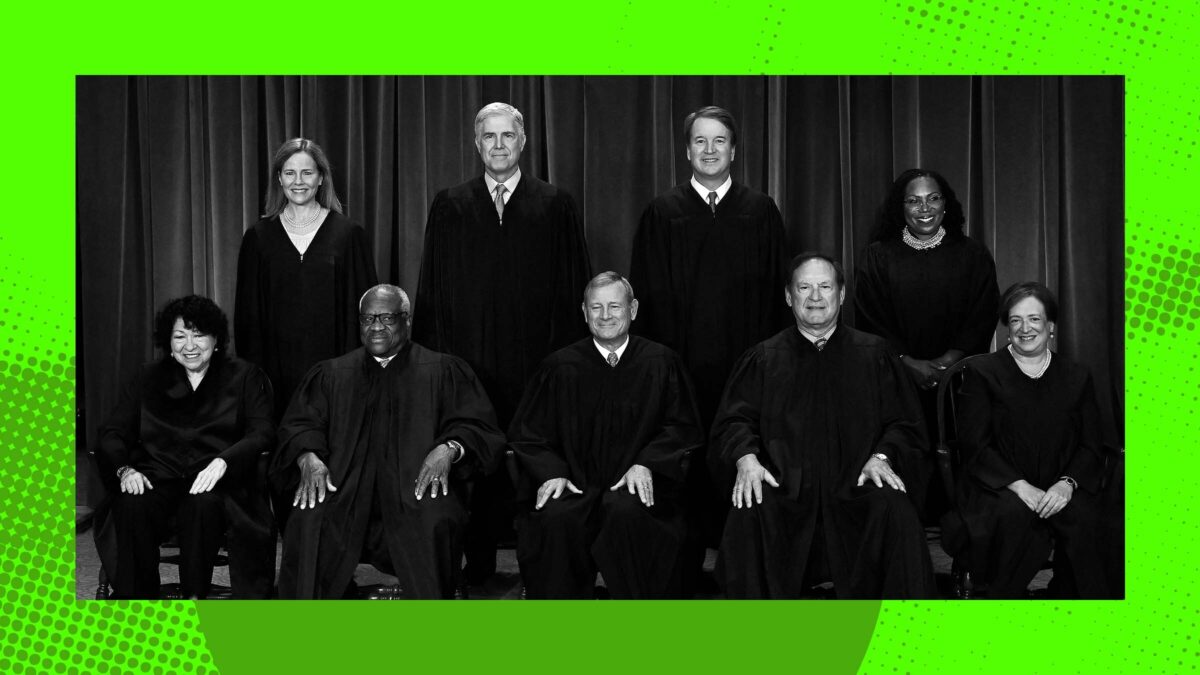

The rush to defend the sanctity of judicial secrecy reflects a tradition among Supreme Court justices, their clerks, staff, and others in the know: deference to the institution in all things. Shrouding their work in secrecy helps the justices to maintain the charade that their decisions are exclusively the product of principled legal deliberations undertaken by the nation’s nine most scrupulously fair legal minds. In reality, justices sometimes do whatever they want to do for no reason other than they have the power to do so. These occasional leaks provide the public with the knowledge necessary to develop informed opinions about the Court, and about what the scope of its authority should be.

This is far from the first time someone inside the Court aired out the justices’ dirty laundry. Two years ago, for instance, someone leaked the draft opinion of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the decision that overturned Roe v. Wade, several months before the final Dobbs opinion was published. The Supreme Court’s sham investigation into the leaker’s identity never named a culprit, so it’s still unclear whether the leaker was trying to change the draft by triggering outrage, or cement the majority by preventing a post-leak defection. The leak was nevertheless irrefutable evidence for those who doubted whether the Court would actually rescind the constitutional right to abortion, and it gave people more fuel in their efforts to pressure Congress to protect reproductive health.

Dobbs is also not the only influential leak of a Supreme Court decision on reproductive rights authored by Justice Samuel Alito. Two years ago, a former anti-abortion activist, Reverend Robert Schenck, wrote a letter to Roberts confessing that he received advance notice of the outcome of Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, after Alito and his wife, Martha-Ann, disclosed it to a donor to his organization over dinner. Schenck told Roberts he used the information to “assist…in preparing for the inevitable announcement,” and shared it with the Hobby Lobby CEO shortly before the opinion’s release. Both the opinion and its leak benefited activists trying to curtail women’s bodily autonomy. Schenck’s decision to come forward about the leak also provided significant evidence about the extent of the bench’s collusion with the conservative movement.

Right now, leaks are one of vanishingly few sources of information about the inner workings of the Court. No federal law governs the preservation of judicial records, and the Federal Records Act explicitly excludes the Supreme Court. Instead, as historian and journalist Jill Lepore wrote in The New Yorker a decade ago, “the decision whether to make these documents available is entirely at the discretion of the Justices and their heirs and executors.” There’s no policy stopping clerks from deleting all emails, secretaries from shredding all drafts, or justices from turning conference memos into papier-mâché. On Justice Hugo Black’s explicit instructions, his children burned his documents shortly before his death, calling their bonfire “Operation Frustrate the Historians.” Leakers keep valuable information on the Court’s functioning from being lost forever to a pyre.

Conservative pundits would very much prefer that the public focus on leakers’ breaches of Supreme Court etiquette rather than the actual harm that the Supreme Court inflicts on the public. But existing regulations are plainly insufficient to get the justices to be responsible and transparent. Unless and until that changes, it’s good for leakers to share with the rest of us what the justices want to keep to themselves.