Earlier this month, the Trump administration announced a sweeping executive order targeting the law firm of Paul Weiss, which, the White House says, has “played an outsized role…in the destruction of bedrock American principles.” The order directed agency heads to terminate any contracts with “entities that disclose doing business with Paul Weiss,” thus subjecting the firm’s clients to the threat of forevermore losing the government’s business unless they decided to hire different lawyers instead. In a firmwide email, Paul Weiss chairman Brad Karp described the order as an “existential threat” that “could easily have destroyed” the firm.

According to The New York Times, also contributing to the sense of impending doom at Paul Weiss were Paul Weiss’s competitors, including Sullivan & Cromwell and Kirkland & Ellis, who quietly approached the firm’s top lawyers and asked if, under the unfortunate circumstances, they were interested in leaving and bringing their multimillion-dollar books of business along with them. Karp, as fearful of losing big-name talent as he was of hemorrhaging clients, hastily struck a deal with the White House: In a post on Truth Social, Trump announced that he’d agreed to revoke the order in exchange for, among other promises, Paul Weiss’s commitments to “not adopt, use, or pursue any DEI policies,” and to donate “the equivalent of $40 million in pro bono legal services” to “support the Administration’s initiatives.” When your dignity is already part of the ransom you’ve agreed to pay, that’s a hell of a premium to add to the top of it.

On the record, both Kirkland and Sullivan & Cromwell—and Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, which the Times says “also mulled” whether to poach Paul Weiss lawyers—denied trying to do so, which is probably what I would say if a Times reporter were to call and ask whether my firm tried to leverage creeping authoritarianism by attempting to climb a few spots in the profits per partner rankings. But in an industry this competitive, trying to lure splashy names from vulnerable rivals is always part of the game, whatever the cause of that vulnerability may be. Any firm reading about Trump’s vendetta against Paul Weiss would be foolish not to place a few calls, or at the very, to least start an internal email chain with some high-priority names on it.

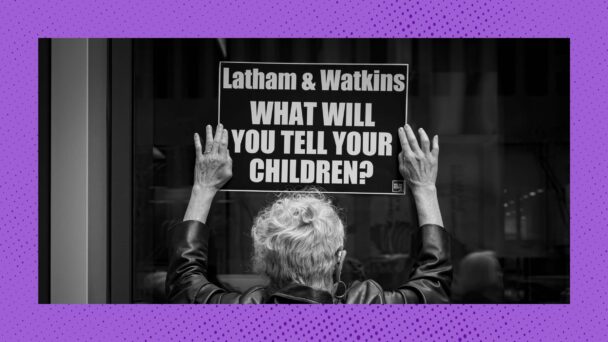

Right now, there is a lot of understandable consternation among many lawyers about the need for The Legal Profession to respond to the Trump administration’s efforts to dismantle it. By my count, Paul Weiss is the fifth firm to get name-checked in an executive order, and although the order indeed gestured at firm’s diversity initiatives, the real source of Trump’s ire is Mark Pomerantz, a former Paul Weiss lawyer who went on to work on the New York state prosecution of Trump for making illegal hush money payments. The most recent order, which targets Jenner & Block, was also prompted by the firm’s previous employment of a former prosecutor whom Trump doesn’t like.

The attacks are only going to get more vindictive and unhinged from here, especially now that Trump has seen that immediate capitulation is a realistic outcome. If the profession doesn’t respond in a meaningful way, it might soon be unable to do so.

The Times’s reporting exposes the practical problem with putting this sentiment into action: The legal profession is not a monolith, and BigLaw in particular—the profession’s best-resourced sector—is a business for everyone involved. One nascent effort to organize lawyers and law firms, a sign-on letter for anyone committed to protecting the “independence and integrity of the legal profession,” has several hundred names attached to it. As of this writing, however, none of them are BigLaw firms, because if these institutions are ever going to “stand up to Trump,” it is only going to happen if they determine that collective action is in their financial interests. In the meantime, firms’ primary incentive is to lay low, cross their fingers, and hope they aren’t next.

(Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

In his email, Karp framed waving the white flag as a prudent business decision, no less than his competitors’ alleged attempts to persuade his colleagues to send out their correspondence on different letterhead. In addition to Paul Weiss’s obligations to its clients, Karp said, he had a “fiduciary duty…to protect the livelihoods of the 2,500 lawyers and non-legal professionals” at the firm, which “weighed extremely heavily” on him during the negotiation process. Although Karp acknowledged that some lawyers might be “uncomfortable” with the result, he continued, the “most important” takeaway is that Paul Weiss “removed a cloud of uncertainty that was hanging over” it, and that everyone could thus get back to billing hours as usual.

I understand that these last few weeks must have been very stressful for Karp and his colleagues, who are not used to the feeling of being the least powerful guys in the room. But I am not sure his analysis—that surrendering to Trump, however distasteful it may feel to some, was the best long-term course of action—is at all correct. Rolling over entails meaningful reputational consequences, too; they just don’t necessarily hit the bottom line immediately, which is why someone in Karp’s position can’t see it.

Take the firm’s client base, for example. If Paul Weiss had elected to fight the executive order, yes, the next day’s Law360 story rattling off the names of all the skittish clients who bailed would have stung. But it’s fair to wonder if Paul Weiss’s surrender will also prompt its clients to explore their options, unsure whether they can entrust bet-the-company litigation to the (very expensive) lawyers who won’t even stand up for themselves. Going forward, too, if you are a Fortune 500 company looking to hire outside counsel, and your choices are Paul Weiss or any one of literally dozens of white-shoe law firms whose leaders didn’t fall all over themselves begging Trump for mercy, I imagine that that choice will not be especially difficult.

In his email, Karp alludes to the poaching on which the Times reported, criticizing unnamed firms for “seeking to exploit our vulnerabilities.” Again, though, the decision to capitulate will also inevitably affect the firm’s retention efforts. Already, some 140 Paul Weiss alums have signed a letter criticizing Karp for inflicting “a permanent stain on the face of a great firm that sought to gain a profit by forfeiting its soul.” Any rainmaker at Paul Weiss who feels similarly has already talked to a headhunter by now, and any associate with decent billables is at least contemplating a lateral move. The problem might be even more acute in recruiting: For law students trying to distinguish between potential employers named after groups of dead white guys, “oh, that’s the one that did the embarrassing Trump deal” is an easy reason to write one less cover letter.

The legal profession has never had to deal with a president issuing a series of increasingly demented executive orders retaliating against specific firms in an effort to settle his long-simmering personal grievances. Everyone in Karp’s position is looking for the least bad route among many unappealing options. But both the other firms’ attempts to peel off Paul Weiss lawyers and Paul Weiss’s response demonstrate the same basic point: BigLaw firms are not going to save the legal profession, because what they care about is preserving their positions of power within it. If an unlucky few are going to go down, the others are going to try to make a buck off their demise.