In the wake of President Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election, a fringe legal theory known as the “independent state legislature” theory is gaining traction among conservatives looking to overturn future elections. Already, Supreme Court Justices Brett Kavanaugh, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas have signaled interest in examining the theory, perhaps as soon as the Supreme Court’s next term.

The Court’s endorsement could open the door to further erosion of democratic processes by shifting power from voters to rogue state legislatures and/or federal judges. Here is a quick explainer of the independent state legislature theory: where it came from, why it’s so dangerous, and how powerful politicians could use it to pick winners themselves when they don’t like election results.

What is the independent state legislature theory?

The independent state legislature theory is derived from Articles I and II of the Constitution, which together state that federal congressional elections and the process of selecting presidential electors shall be prescribed in each state by the “legislature thereof.” Advocates interpret the word “legislature” literally and exclusively to mean a state’s law-making representative body. Some claim that this gives state legislatures sweeping power to regulate federal elections, from voting rights to redistricting, without input from other branches of state government. In theory, legislatures could even enact rules that run afoul of a state’s own constitution, a voter-passed initiative, or a governor’s veto.

By extension, the theory prohibits state election administration officials from doing anything that legislatures do not specifically authorize. And because a state legislature’s power over elections is derived from the federal Constitution, federal courts, not state courts, are supposedly the proper interpreters of whether election officials are complying with the law.

How accurate is this thing?

As a historical matter, not very. For starters, the doctrine gives power to federal judges who are otherwise deferential to state courts interpreting state law. Yet according to law professors Akhil and Vikram Amar, the Constitution’s drafters intended Articles I and II to protect states against undue federal interference. Independent state legislature theory flips this dynamic on its head, requiring federal judges to decide complicated questions of state law unconstrained by state constitutions, state courts, and/or the expressed will of voters. Vikram Amar has called it “law-defying” for how it would upend the typical divisions of power between the state and federal governments.

As a matter of Supreme Court precedent, also not very. In 1916, the Court in Davis v. Hildebrant rejected a reading of the word “legislature” as referring solely to the law-making body, and instead interpreted those provisions to refer more broadly to legislative powers that include things like voter initiatives. The Court held that, as such, voters could reject a state legislature’s redistricting maps by popular referendum

More recently, in 2015, a 5-4 Court shut down Arizona’s attempt to invoke the independent state legislature theory to stop a voter initiative aimed at curbing partisan gerrymandering. “Nothing in that Clause instructs, nor has this Court ever held, that a state legislature may prescribe regulations on the time, place, and manner of holding federal elections in defiance of provisions of the State’s constitution,” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote.

Finally, the theory is notably at odds with the Court’s 2019 decision in Rucho v. Common Cause, in which five conservative justices decided that partisan gerrymandering cases were beyond the reach of federal courts, but left open the possibility that state courts could consider these claims on state law grounds. This decision was widely seen as a victory for Republicans, who consistently oppose efforts to depoliticize the line-drawing process. Yet if the Court were to fully embrace the independent state legislature theory today, legislative map-drawing efforts would be subject to review by federal courts, not state courts. Alito, Gorsuch, and Thomas all signed on to Rucho, but are also interested in a concept that would directly contradict that holding.

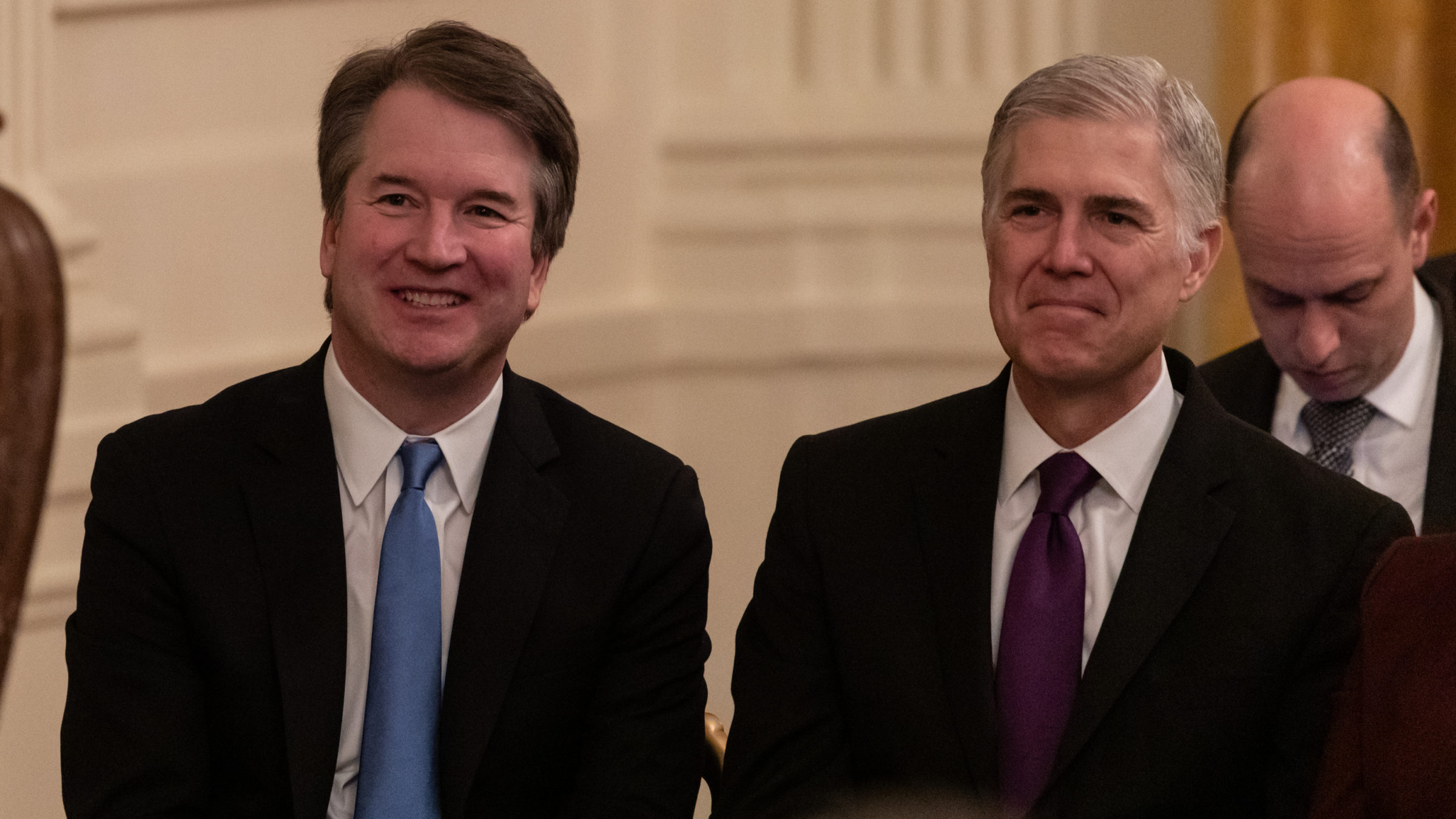

When your co-worker is on some bullshit (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

What are the justifications for the theory?

Primarily, a romanticized understanding of state legislatures as the pinnacle of representative democracy. Proponents like law professor Michael Morley claim the theory promotes accountability by putting elections in the hands of the politically accountable branches. Gorsuch echoed this point in a 2020 concurrence that stayed a district court’s extension of certain election deadlines, praising state legislatures as “the people’s representatives” to whom control over federal elections is properly entrusted.

This rationale is, at best, dubious. As explained by law professor Miriam Seifter, state legislatures are usually a state’s least democratic entity, thanks to, among other things, partisan gerrymandering and near-exclusive use of winner-take-all elections in single-member districts. The independent state legislature theory actually undermines the tools of direct democracy—voter initiative and public referendum, for example—by elevating the state legislature over them. Law professor Josh Douglas has thus called it “dangerous,” noting that “state politicians are the people most interested in crafting the rules of the game to help themselves and their side continue to win.”

When did the theory start making its dramatic jurisprudential comeback?

Rewind to the contested 2000 presidential election between Texas governor George W. Bush and Vice President Al Gore. In a 5-4 unsigned decision, a bare majority of the Court intervened to stop the Florida Supreme Court’s ballot recount order, effectively handing the victory to Bush. In a concurrence written by Chief Justice William Rehnquist and joined by Thomas and Justice Antonin Scalia, Rehnquist invoked the theory to justify the Court’s choice. “This inquiry does not imply a disrespect for state courts but rather a respect for the constitutionally prescribed role of state legislatures,” he wrote.

In dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer critiqued this reliance on the independent state legislature theory as irrelevant and extreme. The claims that were “the focus of the Chief Justice’s concurrence raise no significant federal questions,” Breyer wrote. “I cannot agree that the Chief Justice’s unusual review of state law in this case is justified.”

Anything more recent than that?

In 2020, conservatives invoked the theory in multiple cases challenging the outcome of the presidential election. (One of these conservatives was Ginni Thomas, wife of Justice Clarence Thomas, who told Arizona lawmakers that they had the “power to fight back against fraud,” and that the responsibility to appoint electors—pro-Trump electors—was “yours and yours alone.”)

Shortly before Election Day, Pennsylvania Republicans requested an emergency stay to overturn a state supreme court decision that had extended mail-in ballot deadlines amidst COVID-19 concerns about in-person voting. Although the Court denied the request, Alito, Thomas, Neil Gorsuch wrote that the Court’s handling of the matter could lead to “serious” problems. “The provisions of the Federal Constitution conferring on state legislatures, not state courts, the authority to make rules governing federal elections would be meaningless if a state court could override the rules adopted by the legislature simply by claiming that a state constitutional provision gave the courts the authority to make whatever rules it thought appropriate,” Alito wrote.

Gorsuch struck a similar note in another 2020 case, when the Court declined to preserve a lower federal court order extending Wisconsin’s mail-in ballot deadline. “Legislatures make policy and bring to bear the collective wisdom of the whole people when they do,” he wrote, and judges cannot “undo this arrangement just because we might be frustrated.” In a separate concurrence, Kavanaugh cited Rehnquist’s opinion in Bush v. Gore as if it were suddenly binding precedent. “The text of Article II means that ‘the clearly expressed intent of the legislature must prevail’ and that a state court may not depart from the state election code enacted by the legislature,” he wrote.

More recently, Republicans in North Carolina and Pennsylvania relied on the independent state legislature theory to argue that state courts cannot intervene in redistricting conflicts. Republicans in Pennsylvania requested that the Court block the implementation of maps that state courts ordered in response to racial gerrymander challenges. “The state supreme court cannot arrogate to itself powers that the Constitution specifically assigns to ‘the Legislature,’” they wrote in their request for an injunction. The Court denied it.

When a Republican-controlled legislature does whatever the hell it wants (Photo by Cheriss May/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

The Court denied it! Hey, that seems good!

Alas, in North Carolina, the conservative justices were far more sympathetic to the independent state legislature theory. As in Pennsylvania, Republicans in Moore v. Harper asked the justices to overturn Pennsylvania redistricting maps that a state court had ordered to ensure racial parity in voting. Although the Court denied the request, Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch dissented. “This case presents an exceptionally important and recurring question of constitutional law, namely, the extent of a state court’s authority to reject rules adopted by a state legislature for use in conducting federal elections,” Alito wrote.

Kavanaugh concurred, but wrote separately to encourage the Court to analyze the issue after full briefing and argument. “I agree with Justice Alito that the underlying Elections Clause question raised in the emergency application is important,” he wrote. In a wild coincidence, Kavanaugh is one of three sitting justices who worked in some capacity to stop the recounts in Bush v. Gore. That Rehnquist concurrence earned only three votes in 2020, but seems to get a little more mainstream within the Court with each passing year.

How bad could this get, exactly?

State legislatures are disproportionately dominated by Republicans, who control 62 state legislative chambers to the Democrats’ 36. When an unsettling number of Republican state lawmakers remain committed to the Big Lie that President Joe Biden stole the 2020 election, a legal theory that would give them unfettered authority to manipulate or even overturn future election outcomes is, to say the least, problematic.

The impact of the Court’s endorsement would be seismic. A robust independent state legislature theory could bar state courts from considering state constitutional claims regarding election regulations, and perhaps limit governors’ ability to veto legislation, too. A particularly scary tactic favored by Republican legislatures—trying to appoint electors willing to ignore the popular vote—is solidly within the scope of what the theory might allow.

A new era of the independent state legislature theory would warp the Schoolhouse Rock conception of democracy beyond recognition, enabling lawmakers who are already in power to take over elections without meaningful oversight or consequences. It is, in short, very bad, which is why you’re only going to hear more about it in the months and years to come.