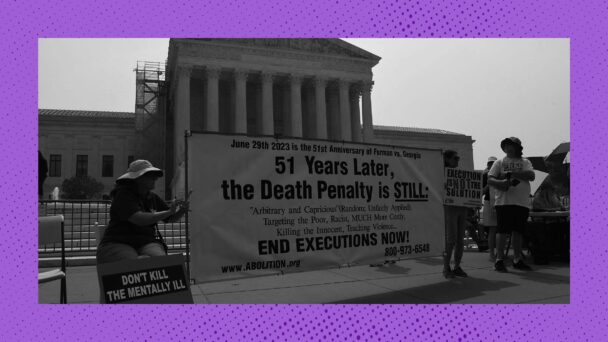

Of the 16 people executed by the federal government since it reinstated the death penalty in 1988, all but three were killed during President Donald Trump’s first term. Over half of those executions—seven of 13—occurred in the 11 weeks after news networks called the 2020 election and before President Joe Biden took office.

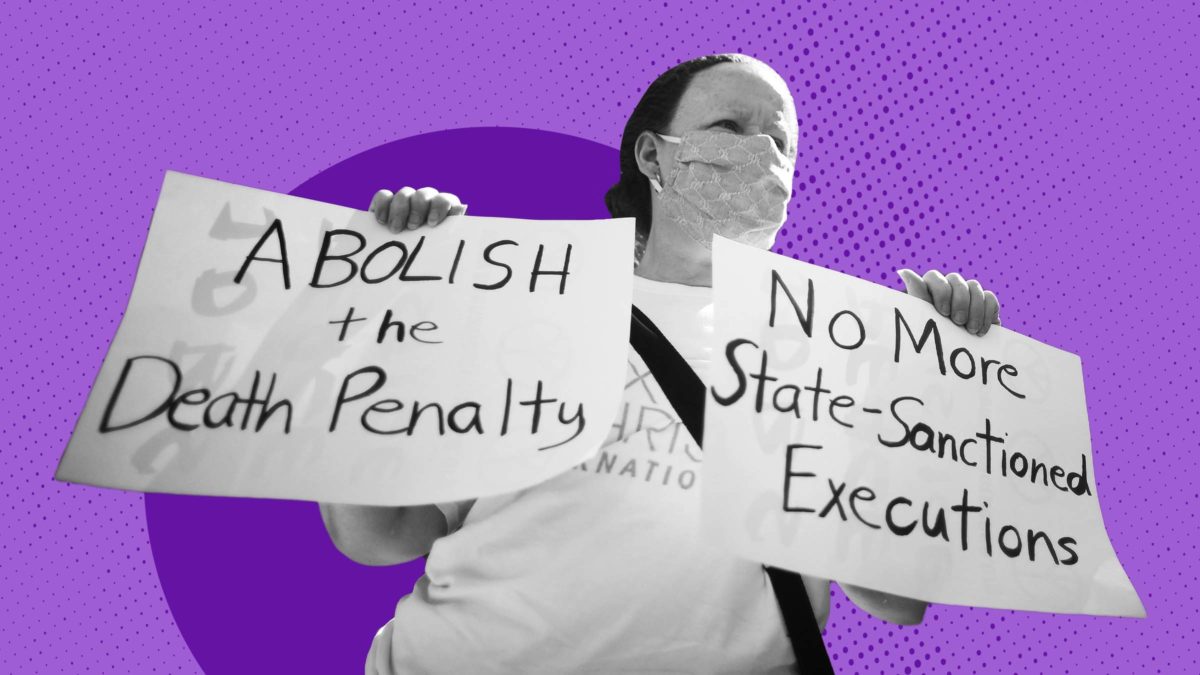

Four years after that, as Trump prepared to retake the White House and kick off another execution spree, opponents of capital punishment urged Biden to stop him from doing so. Biden mostly listened, commuting the sentences of 37 of the 40 people on federal death row to life sentences without the possibility of parole. (The three exceptions were the men convicted of the 2018 attack at Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh; the 2015 attack at Mother Emanuel AME Church, a famed Black church in Charleston, South Carolina; and the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.) By the end of his term, Biden granted 4,245 total acts of clemency—more than any other president on record.

Now, the conservative legal movement is trying to take the clemency back. Last month, Trump argued on Truth Social that “many” of Biden’s pardons and commutations were “VOID, VACANT, AND OF NO FURTHER EFFECT.” Yesterday, The New York Times reported that Trump’s interim U.S. attorney in Washington, D.C., Ed Martin, has been sending letters to former Biden aides demanding information about whether Biden was competent to issue pardons in the last days of his term, especially to his family members against whom Trump had vowed revenge. In one letter, Martin expressed skepticism about Biden’s ability to issue “so many pardons across so many fields,” and claimed to be “in contact with some of the recipients of the pardons who expressed some concern about them.”

These efforts to delegitimize Biden’s grants of clemency got a recent assist from Judge Andrew Oldham, a Trump appointee to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals who desperately desires a promotion to the Supreme Court. In March, Oldham authored a concurring opinion in United States v. Sanders that both treated Trump’s dubious claims as credible and also provided Trump with new specious legal arguments to deploy in defense of his killing campaign. In doing so, Oldham provided a compelling example of how conservative judges work with Republican elected officials to reach their shared goals, repackaging political talking points as vaguely-legal-sounding arguments for like-minded lawyers to make in court.

Trump’s specific claim is that the pardons Biden issued to members of the U.S. House Select Committee on the January 6 Attack were invalid, because, Trump alleged, Biden signed them using an autopen. “In other words, Joe Biden did not sign them but, more importantly, he did not know anything about them!” Trump wrote.

The particular writing instrument used to sign a pardon does not, in fact, pose a constitutional problem, as President George W. Bush’s Office of Legal Counsel explained at length in 2005. Pens also had no relevancy to the legal questions in Sanders, the appeal of one of the men whose death sentences Biden commuted to life without parole. Oldham had much to say on the matter anyway. “Questions have arisen about the flurry of last-minute pardons issued by the Biden Administration,” he said, since “some or all were allegedly effectuated via autopen.” Oldham also noted Republican Speaker of the House Mike Johnson’s comments that “Biden genuinely did not know what he had signed in at least one instance toward the end of his presidency,” as if Johnson’s career as a self-described frontline soldier in a culture war qualifies him to make reliable assessments about Biden’s mental state at any given moment.

Oldham’s next argument appears crafted to implement an executive order Trump issued in January, which directed Attorney General Pam Bondi to “evaluate” whether the 37 people whose death sentences Biden commuted “can be charged with state capital crimes” instead. Per Oldham, the Founders envisioned “two primary purposes” for the pardon power. First, it was a way “to secure justice for those convicted of crimes despite being legally or morally innocent,” and second, it was a tool for “promoting the public interest”—chiefly in cases where pardons could help keep the peace or get an accomplice to testify.

Therefore, Oldham says, Biden’s grants of clemency don’t make the cut. “It is hard to see how the Biden Administration’s midnight pardon of Sanders—or any of the other 36 pardoned murderers—fits with the history and tradition of the pardon power,” he wrote.

Finally, Oldham claimed that “the Framers explicitly adopted the king’s traditional pardon power into the Constitution,” pointing to legislation enacted by the English Parliament in 1389 as evidence that “the king’s power to pardon was not unlimited.” But the U.S. Supreme Court directly rejected these limits on the president’s pardon power in 1866, holding in Ex parte Garland that the Constitution confers “unlimited” power on presidents to pardon federal crimes, with the exception of “cases of impeachment.” Oldham does not mention this aspect of Ex parte Garland in his opinion, lest it stifle his creativity.

Oldham’s concurrence gifts the Trump administration manufactured rationales to try to undermine Biden’s commutations. It suggests that Trump’s middle-of-the-night social media posts about autopens could be the basis of a legitimate legal challenge, and that pardons are only justified if they are granted for one of the two reasons he identified.

Such an intrusion into executive power is the kind of thing that would normally spur right-wing backlash, as Republicans regularly adopt legal theories to maximize executive authority. But here there’s no such problem, because a Republican judge is just trying to support a Republican president’s effort to undo the actions of his Democratic predecessor. Oldham is signaling to the Trump administration exactly what they should put in their briefs when they come before him, so that it can get back to the business of killing.