What is to be done about the Supreme Court? It’s a weighty question with which progressives inside and outside Congress are grappling, as judges will be a major obstacle to a Green New Deal, Medicare for All, and potentially even more modest legislative programs. The Court’s 6-3 conservative majority and the hundreds of lower court judges appointed by Presidents Trump and Bush are sure to limit the effectiveness of progressive statutes, narrow their scope, or strike them down in their entirety.

Although the current Congress appears unlikely to pass major progressive legislation, any future Democratic Congresses—particularly if they lean strongly to the left—will first have to address the power of the courts before they can implement their agenda.

Drawing on President Franklin Roosevelt’s efforts to protect New Deal legislation from judicial invalidation during the Great Depression, many on the left have advocated for legislation to expand the Court. Yet as scholars like Ryan Doerfler and Samuel Moyn have argued, this proposal, by itself, wouldn’t address the awesome, unaccountable power of the institution. A meaningful Court reform agenda must also include disempowering provisions that reduce the outsized role of the courts in American life. And among the many ways Congress can do so is by taking a more precise approach to its primary task: drafting statutes.

A major portion of the federal judiciary’s docket concerns matters of statutory interpretation. What does a particular federal law mean? Did a regulator reasonably interpret a statute? Vague, ambiguous, or open-ended provisions give conservative activist judges opportunities to substitute their policy preferences for those of the elected legislature’s. Enacting clearer, more detailed statutory text reduces judicial discretion and can limit this usurpation of legislative power.

This is hardly a failsafe method of reining in judges; as last month’s decision striking down the mask mandate for passengers on buses, planes, and trains shows, judges determined to reach a certain result in a particular case can find a way to do so. But this strategy can still be part of a larger progressive project to disempower the courts. The history of two major federal statutes—the Sherman Act and the Truth in Lending Act—highlights the dangers of brief, generally worded statutes, and the advantages of putting in the time and effort to pass more specific legislation instead.

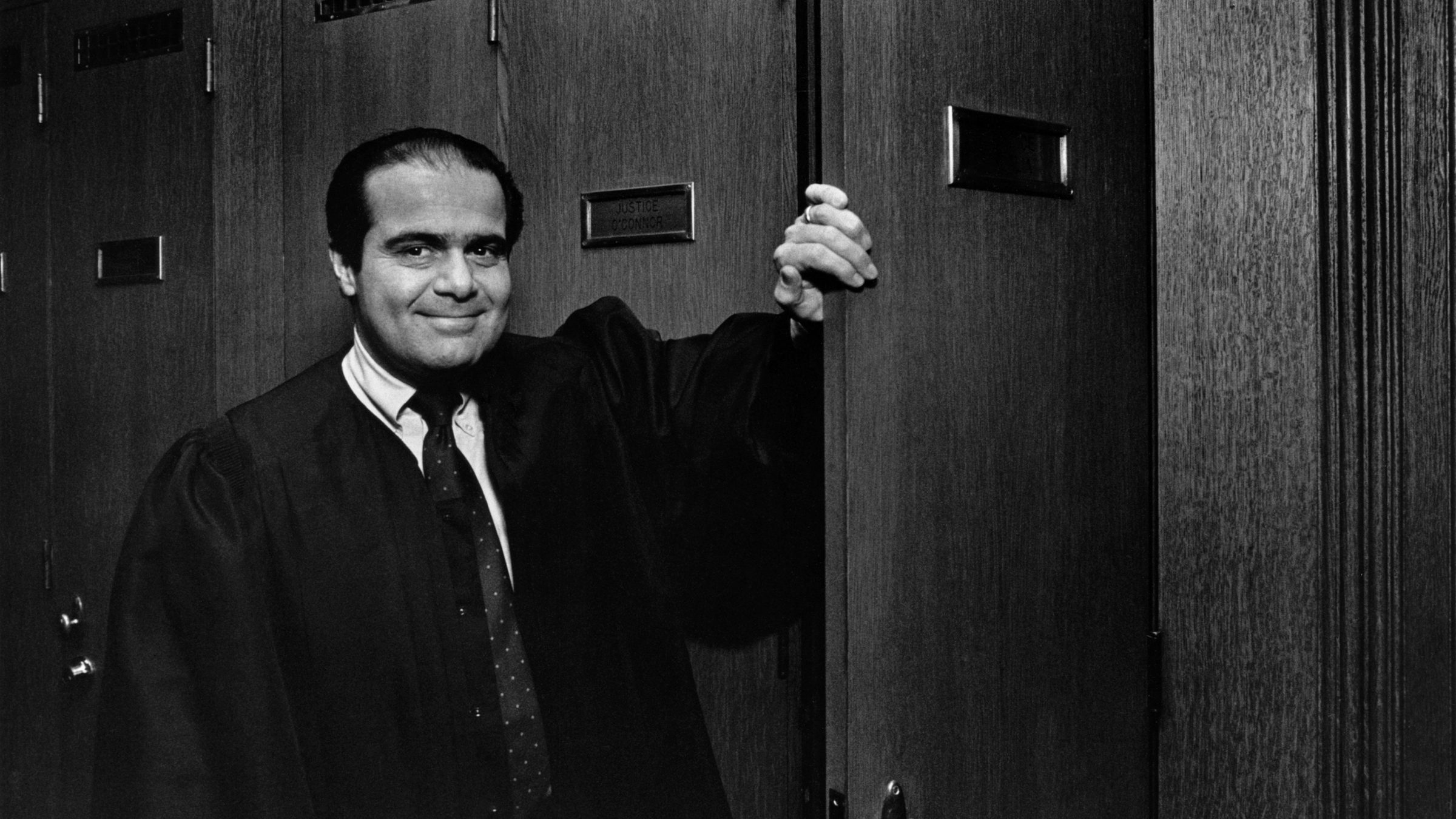

When you have the chance to decide a vague statute means what you think it should mean (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

The history of federal antitrust law is, in large measure, a history of judicial supremacy. In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Act, the first federal antitrust law that prohibits, among other things, “restraints of trade.” In interpreting this ban, the Supreme Court was split between literalists who interpreted the law to prohibit all restraints of trade, and a “rule of reason” faction who believed the law only outlawed unreasonable ones. In 1911, the latter camp prevailed: In an 8-1 decision in Standard Oil v. United States, the Court held that the Sherman Act bars only unreasonable restraints of trade, and that the justices would decide which restraints are unreasonable and which are not. In dissent, Justice John Marshall Harlan accused the majority of “judicial legislation” and usurping the function of Congress.

Standard Oil provoked a strong reaction in Congress. Many progressives and populists argued the Supreme Court had effectively rewritten the law the legislature had passed 20 years earlier. To reassert their authority over antitrust policy, Congress passed two new laws: the Clayton Act, which restricted specific practices such as mergers, exclusive dealing, and tying, and the Federal Trade Commission Act, which created the FTC and gave it the flexible power to identify and prohibit “unfair methods of competition.” Congress did not, however, repeal the Sherman Act; courts were free to continue treating this law as an effective delegation of policymaking authority.

For a brief period in the mid-20th century, courts interpreted the Sherman Act in light of its statutory text and legislative history. But since the late 1970s, judges have treated the Act’s broad language as a license to make national economic policy. Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford appointed a total of five justices to the Court, all of whom (to varying degrees) were more conservative than their predecessors.

This new Court quickly made its mark in antitrust law: In a 1977 decision called Continental TV v. GTE Sylvania, the Court had to decide whether manufacturers could restrict where retailers carried and sold their goods—televisions, in this case. The Court held that manufacturers could impose such contractual restraints because they, in theory, promote the efficient distribution of goods, even though they impinge on dealers’ freedom to trade. In a concurrence, Justice Byron White noted this assertion of raw power, and observed that protecting the autonomy of retailers and wholesalers was “without question more deeply embedded in our cases” than the promotion of distributional efficiency that animated the majority’s decision.

What White called out would become the norm in the Supreme Court’s antitrust jurisprudence. In 1988, Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for a six-justice majority in Business Electronics v. Sharp Electronics, asserted that “the Sherman Act adopted the term ‘restraint of trade’ along with its dynamic potential. It invokes the common law itself, and not merely the static content that the common law had assigned to the term in 1890.” Relying on this “dynamic” common law power, the Court read legislation that contravened the majority’s views narrowly and held their preferred economic theories would guide antitrust decisions. Through invocation of the common law, the Court assumed enormous power to make and remake the Sherman Act as its justices saw fit.

The most audacious judicial policymaking in antitrust may have been in a 2004 decision called Verizon Communications v. Trinko. The case concerned when a federally regulated telecom monopolist’s refusal to do business with a rival constituted illegal monopolization. In a case concerning anti-monopoly law, Scalia’s majority opinion praised monopoly. “The opportunity to charge monopoly prices—at least for a short period—is what attracts ‘business acumen’ in the first place; it induces risk taking that produces innovation and economic growth,” he wrote. This decision cast doubt on the basic purpose of the Sherman Act’s ban on monopolization, and gave broad license to the lower courts to reject antitrust challenges to the practices of dominant corporations.

When you see a beautiful, perfect monopoly (Photo by Janet Fries/Getty Images)

If the history of Sherman Act enforcement shows how vague legislation can go wrong, the Truth in Lending Act’s history shows how more specific legislation can work. Congress enacted TILA in 1968 with the aim of promoting “the informed use of credit” and has amended it several times since, most notably in the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. The law covers most forms of credit and imposes disclosure, error resolution, and underwriting obligations on credit card issuers and mortgage lenders.

The statute is implemented by detailed regulations, collectively known as Regulation Z. Previously, they were administered by the Federal Reserve; following the enactment of Dodd-Frank, they have been amended and enforced by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (Disclosure: I worked at the CFPB from 2015 to 2018.) On top of these binding regulations, the CFPB has issued extensive guidance materials that further clarify its supervisory and enforcement priorities.

TILA’s detailed statutory text and the regulatory regime that flows from it has sharply limited the scope of judicial policymaking. When courts hear cases concerning TILA, the specificity of statutory law has restricted their ability to make policy. For instance, Scalia, writing for a unanimous Court in 2015, concluded that consumers who wanted to rescind a home mortgage within three years of taking out the loan only had to provide written notice to their lender, and not file a lawsuit as some lower courts had held. The Court held that the plain text of TILA didn’t afford much wiggle room and thus compelled this result.

Passing this type of statute is harder, of course, and takes more time and effort. The more specific a statute, the more opportunities there are for negotiations among lawmakers to break down. But employing this strategy to the greatest extent possible can yield statues that could remain effective, in large measure, even if the Supreme Court were to revive a version of the non-delegation doctrine and restrict the power of agencies like the CFPB going forward.

In Bostock v. Clayton County, the Court held that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employers from discriminating against employees based on their sexual orientation or gender identity. In his majority opinion, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote, “When the express terms of a statute give us one answer and extratextual considerations suggest another, it’s no contest. Only the written word is the law, and all persons are entitled to its benefit.”

Future Congresses should heed the words of one of the high court’s self-described textualists and reduce the role for judicial discretion by enacting clear, specific laws in the model of the Truth in Lending Act. The history of the Sherman Act shows the perils of the alternative approach.