Very bad things can happen to people in immigration court. The court can order people to be held indefinitely, as long as the government thinks it can find a country that will take them. The court can send people to countries they haven’t seen since they were in preschool. It can send them to countries they’ve never set foot in before, even if those countries are in the middle of a civil war. These results are in addition to immigration court’s usual, everyday practice of breaking apart families by sending people away from their spouses, children, and communities.

With consequences this serious, you would think that process in immigration court would be substantial, filled with all the procedural safeguards the American legal system can offer. You would be wrong. Instead, the people whom ICE is snatching off the street are thrust into immigration court, a sham in which three-year-olds represent themselves, not all the hearings are fully translated, and the judges and prosecutors both have the same boss: Attorney General Pam Bondi, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, and, ultimately, President Donald Trump.

When most people think of “courts,” they usually think of courts that fall within the judicial branch of the federal government. Immigration courts, however, are part of the executive branch; they are housed in the Executive Office for Immigration Review, a division of the Department of Justice. The judges are Department of Justice employees, and prosecutors represent the Department of Homeland Security. The setup is the same at the first-tier appellate level, the Board of Immigration Appeals, which is also housed within the Department of Justice.

From there, noncitizens can appeal their cases to the federal courts of appeals, where the judge is an Article III judge. But the prosecutor they face is still employed by the Department of Justice—the employer of the judges in the immigration courts below.

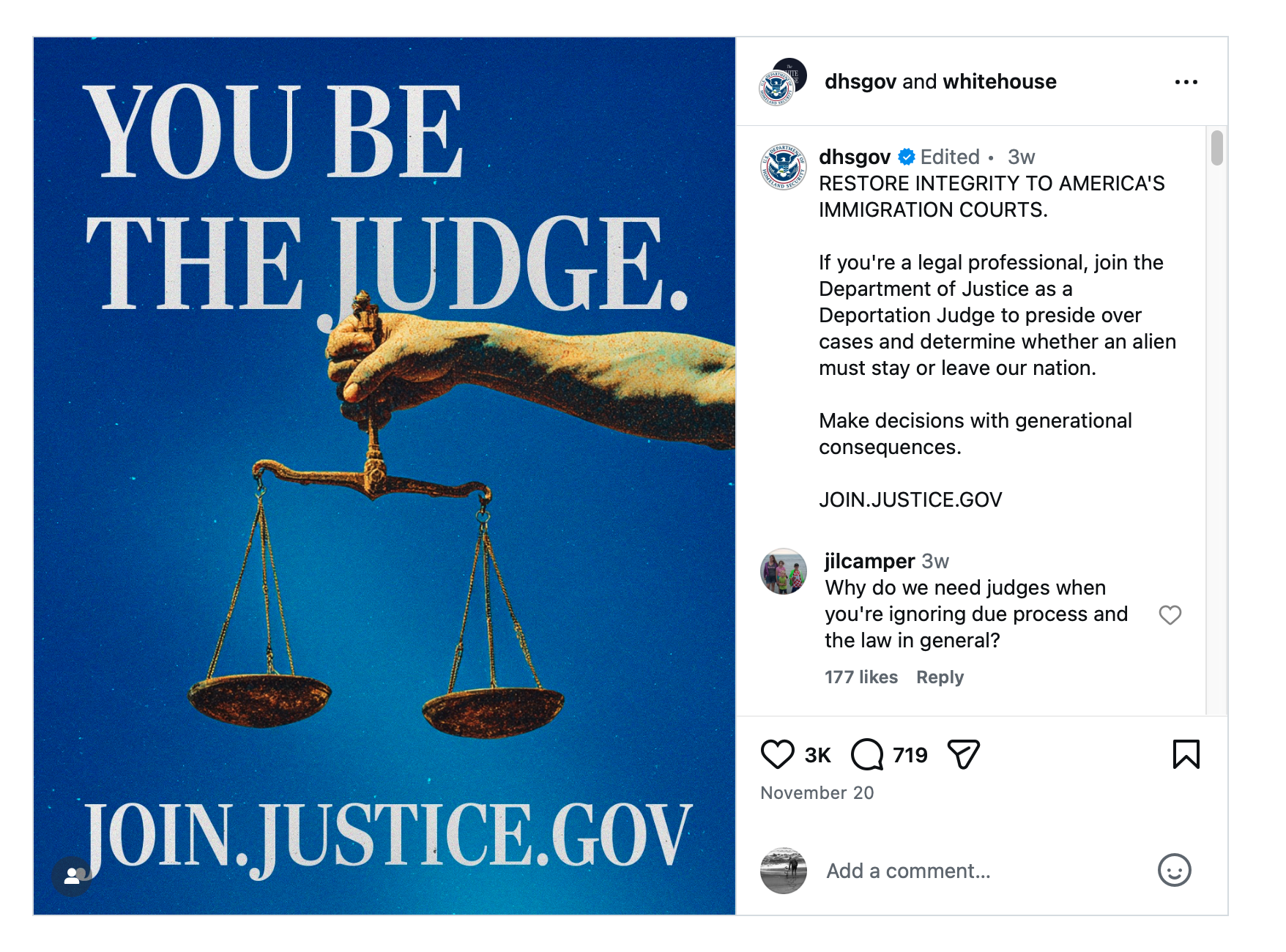

In other words, a noncitizen in immigration court faces opposition from both the prosecutor and the judge, who both follow orders from the president. Perhaps the neatest illustration of this problem came in November, when the Department of Homeland Security account posted on Instagram an advertisement seeking to hire “deportation judges” for the Department of Justice.

Immigration court’s bizarre location within the constitutional framework is only one of many problems with this body. Even though the court makes decisions about liberty, counsel is not provided at government expense, as it is in the criminal system. Every year, tens of thousands of children are put through immigration court, and roughly half of them do not have lawyers.

Immigration court doesn’t have detailed rules of procedure, either. The Code of Federal Regulations establishes extremely basic rules of immigration procedure, but all they really do is give EOIR the power to create its own procedures. EOIR has, in turn, put together a “practice manual,” which establishes basic things like filing deadlines. But the first chapter of the manual explicitly empowers immigration judges to decide that the rules are not binding in a given case before them. EOIR can also revoke or revise the manual at any time, with no notice to litigants.

What this means in practice is that prosecutors can violate most or all of the rules and suffer no consequences whatsoever. Evidence—some ancient deportation order, for example—disclosed by the government on the day of trial? That’s fine in immigration court, though it would be a major constitutional violation in a criminal trial. When this happens, immigration judges won’t even give the noncitizen a new court date so they can review the new material.

There are also no fixed rules of evidence in immigration court, so the immigration judge has tremendous latitude in allowing evidence that would never be admissible in a criminal or civil court. Take the threshold issue of whether or not a person is a noncitizen. The burden of proof is on the government. However, the most common method of proof is a police report, otherwise known as an I-213. If the report states that someone said the respondent is a noncitizen, the government has met its burden, even without the testimony of the arresting agent.

This testimony would allow the noncitizen to challenge an individual agent’s credibility in a particular matter. In criminal trials, this right is protected by the Confrontation Clause in the Sixth Amendment. But the Department of Justice has decided that in immigration court, I-213s are inherently trustworthy. Sometimes the name of the agent is even redacted, so even if immigrants had the right to cross-examine, calling the agent to testify would be impossible.

If a case makes its way through the Department of Justice and arrives at a federal appeals court, you might think that a noncitizen could get some justice. But you would again be wrong. In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, a statute that stripped federal courts of jurisdiction to hear cases that deal with many immigration issues. In 2022, the Supreme Court made matters worse by holding in Garland v. Gonzalez that federal appeals courts do not have the power to broadly enjoin unlawful immigration policies perpetrated by the government. In practice, this means that every person who is a victim of the government’s abuse must sue to protect their own individual rights.

(Photo by Selcuk Acar/Anadolu via Getty Images)

Nowhere is this rule more impactful than in cases of immigration detention. Although the law says that immigration detention is not punishment, in practice, it is not much different from criminal confinement. Immigrants are often housed in the same facilities as people convicted of crimes. They wear jumpsuits. They are often shackled. Calling loved ones is often expensive. And under IIRAIRA, many immigrants in detention are not eligible for release, or even for hearings in order to determine whether they can be released. This, too, is the fault of IIRAIRA, under which “arriving aliens” are not entitled to bond. As a result, the government can simply decide that someone is an “arriving alien” and keep them locked up.

Over the past several months, the Trump administration has gleefully abused this power, claiming that any person who crossed the border without authorization at any time, even years ago, is an “arriving alien” under IIRAIRA, with all the attendant limits on their legal rights. Hundreds of people have challenged this policy in federal court, and judges have been ordering people released. But it can take months for these lawsuits to succeed, and until there is a clear federal decision outlawing this policy, noncitizens will continue to be locked up.

The black robes and raised platforms might make you think immigration courts represent some form of justice, but it’s just legal theater. These executive branch offices are fast tracks to detention and deportation, leaving behind wrecked lives and splintered families.