This article is published as a collaboration between Balls & Strikes and Bolts.

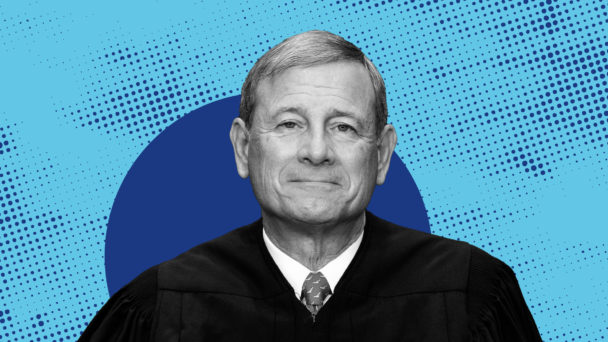

Conservative justices on the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that federal judges could not entertain complaints of partisan gerrymandering. In its landmark 5-4 decision Rucho v. Common Cause, the court said that it’s not for federal courts to decide whether an election map is designed to give one party an illegal advantage. But Chief Justice John Roberts assured plaintiffs that his decision does not leave them powerless to stop partisan gerrymandering since they still have a path for litigation: state courts.

The Rucho decision did not “condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void,” Roberts wrote, since states “are actively addressing the issue on a number of fronts.”

New Hampshire last week became the latest state to show the promise was largely illusory.

Its state supreme court ruled that it couldn’t decide whether the state’s election maps are illegal partisan gerrymanders because that’s not something that state judges should be deciding either. The 3-2 decision—with the three judges appointed by Republican Governor Chris Sununu in the majority—left in place the GOP gerrymanders signed into law by Sununu. This likely locks the party’s structural advantages in New Hampshire’s Senate and executive council through the 2030s.

And it condemns complaints of partisan gerrymandering claims to echo into a void after all, with nowhere to turn in either federal court or New Hampshire court.

When a partisan gerrymander survives (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

The court said plaintiffs could address their grievances by getting state lawmakers to pass redistricting reform. But the odds of such a reform are low since the New Hampshire legislature is already gerrymandered, a circular dynamic that explains why voting groups tried to turn to federal and state courts on the issue. Any bill would have to be approved by the state Senate, a body whose districts have long been drawn to give Republicans an edge.

The New Hampshire decision adds to a trend in the nation since Rucho, with other state courts retreating from Roberts’ assurance and showing that they can just as easily refuse to answer the same questions. Earlier this year, for example, North Carolina’s supreme court ruled that partisan gerrymandering lawsuits can’t be brought under the state constitution, reversing past decisions to the contrary and paving the way for maps meant to maximize the GOP’s power.

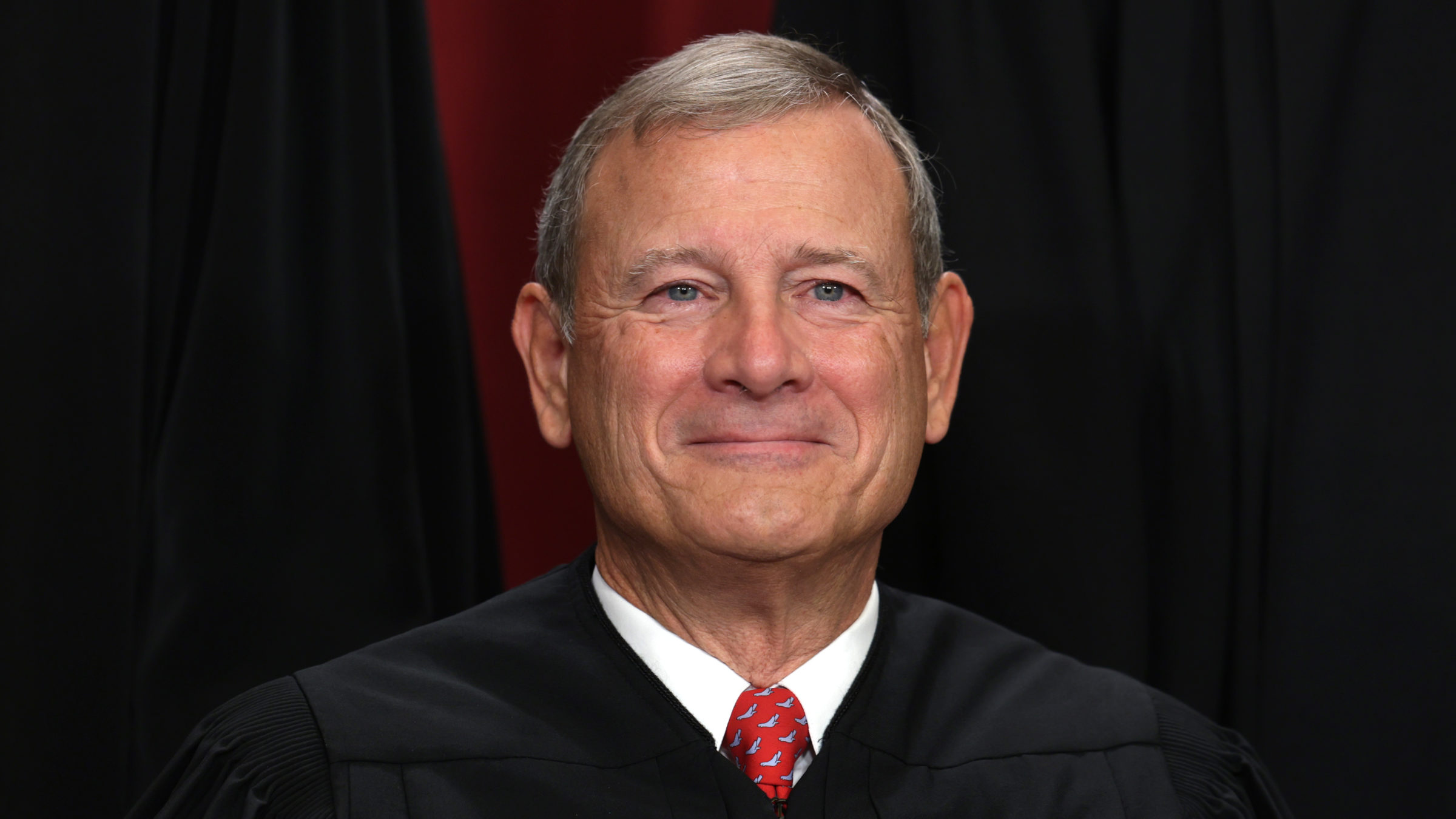

New Hampshire Republicans won complete control of state government in 2020. They then proceeded to cement their advantage after the decennial census, adopting districts for the state Senate and executive council that created more Republican-leaning seats. A group of voters challenged the maps in court, alleging that they were partisan gerrymanders that violated New Hampshire’s constitution.

But New Hampshire’s supreme court upheld the maps’ constitutionality on Nov. 29. The court declined to even consider the merits of the challenge, holding instead that partisan gerrymandering is a policy matter for other institutions to debate, and is a non-justiciable political question.

In practice, this means that no case alleging partisan gerrymandering, regardless of how egregious, can be brought in state courts.

The New Hampshire court argued that there is no consistent method through which state judges could adjudicate such cases: no “discernible and manageable standards for adjudicating partisan-gerrymandering claims.” The language mirrors the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Rucho on how federal courts should approach partisan gerrymandering claims: Roberts argued in that case that adjudicating such claims is overly subjective. “There are no legal standards discernible in the Constitution for making such judgments, let alone limited and precise standards that are clear, manageable, and politically neutral,” the chief justice wrote.

The New Hampshire court’s decision flips an important part of the rationale in Rucho on its head. Roberts’ opinion also doubled as an ode to federalism; even as he sidelined federal courts, he invited states to look to their own laws and constitutions for alternative protections against partisan gerrymandering that don’t rely on the U.S. constitution. Writing in 2019, he offered as an example a 2015 decision by Florida’s supreme court striking down a congressional map as an illegal gerrymander under the state constitution.

Plaintiffs in New Hampshire asked state courts to similarly consider their own constitution. But in closing the door on their challenge, the state supreme court heavily relied on Rucho—calling it “directly on point” even though Rucho was interpreting the U.S. Constitution—and it drew extensively from Roberts’ opinion, even as Roberts invited states to chart their own path.

“Provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply,” Roberts wrote in Rucho, but that approach can’t get out of the starting blocks if a state court then turns to Rucho to decide how to interpret its state constitution.

When a state supreme court stops a partisan gerrymander (Photo by Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images)

Florida’s constitution, unlike New Hampshire’s, contains a clause that expressly restricts partisan gerrymandering. But even in states without such an express prohibition, some courts have found implied protections against partisan gerrymandering. In the last several years alone, courts in Alaska, Maryland, New Mexico, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania have all affirmed such protections.

In their arguments to the New Hampshire supreme court, plaintiffs pointed to these decisions. They argued that the guarantee of “free” elections in New Hampshire’s constitution (which does not exist in the U.S. Constitution), along with other free-expression rights, established a right of voters to elect representatives on equal footing with each other.

The court found this unpersuasive. It reiterated that developing and consistently applying standards for reviewing partisan gerrymandering isn’t possible in practice. As a “telling” sign of this inconsistency, the New Hampshire justices pointed to recent events in North Carolina, where the state supreme court struck down GOP gerrymanders in 2022 before reversing itself this year.

But North Carolina’s court didn’t just change the standards for deciding whether maps are unconstitutional, or apply old standards differently. It simply ruled that this is not a question that judges can rationally decide, in language very similar to the New Hampshire decision.

“There is no judicially manageable standard by which to adjudicate partisan gerrymandering claims,” North Carolina Chief Justice Paul Newby, a Republican, wrote in February. “Courts are not intended to meddle in policy matters.”

New Mexico’s supreme court offered the opposite answer this year when it confronted a similar question.

It ruled that state courts can entertain claims of partisan gerrymandering, and decide whether a map is unduly giving an advantage to a party. To get around the concern that there’s no criteria judges could manage, the court identified a set of standards with which to analyze maps. It adopted a three-part test laid out by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan in her dissent in the Rucho case; Kagan proposed that courts could strike down a map if they have proof that its creators’ purpose was to “entrench their party in power;” that it has had “the intended effect”; and, if so, that mapmakers cannot provide a “legitimate, non-partisan justification” for the map.

The same court in November then upheld New Mexico’s congressional map, which delivered Democrats an additional seat in 2022, ruling on the merits that it did not violate Kagan’s test.

The decision is a reminder that a state court’s decision to hear partisan gerrymandering claims does not mean they’ll automatically strike down a map. And when such cases come up, there’s no telling how left-leaning and right-leaning justices may rule, depending on who has drawn maps; in New York State last year, it was the conservative-leaning judges who struck down gerrymanders drawn by Democrats over the objections of more liberal judges.

But these decisions also underscore the widening contrast between courts on the first-order question of whether they’ll even entertain such claims: on whether partisan gerrymandering is a judiciable question.

Conservative jurists have been more likely to rule that it is not. The North Carolina reversal came after the court flipped from 4–3 Democratic to 5–2 Republican last year. The Rucho decision was a similarly narrow 5-4 win for the court’s then-five conservative justices.

And in New Hampshire, the decision to reject the partisan gerrymandering claims came down to a 3–2 vote, with the 3 justices nominated by a Republican governor in the majority, and the two nominated by Democratic governor dissenting.

One of the justices in the majority was Chief Justice Gordon MacDonald, whose nomination by Sununu was initially rejected by the executive council when it was under Democratic control. MacDonald was then confirmed to his seat when the council flipped to the GOP in 2020.

One of the Democratic-nominated justices who dissented in this case, Gary Hicks, left the court the day after the court issued its decision because he hit the mandatory retirement age. Sununu has nominated Melissa Beth Countway, a local judge, to replace him.

Gov. Chris Sununu (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Even Florida has come a long way since Roberts mentioned its supreme court: The mere threat that its new conservative justices may now shrug off partisan gerrymandering complaints has made the state’s existing protections virtually toothless.

After voters amended their state constitution in 2010 to add provisions against partisan gerrymandering, Florida’s supreme court used those provisions to strike down state maps in 2015 for being “tainted” by partisanship. But by the time Republicans adopted a new set of aggressively gerrymandered maps masterminded by Governor Ron DeSantis in 2022, Florida’s judicial landscape was very different: The supreme court’s liberal majority had been wiped out, replaced by hard-right justices appointed by DeSantis.

While plaintiffs initially filed a lawsuit challenging the state’s new congressional districts as partisan and racial gerrymanders, they later dropped all of their partisan gerrymandering claims, perhaps out of a concern that the Florida supreme court would be unwilling to meaningfully enforce the anti-gerrymandering provisions in the constitution.

Looming over all of this is the threat that the U.S. Supreme Court could step in against a state supreme court that actually does strike down a state map as a partisan gerrymander.

In its June decision in Moore v Harper, the court rejected the so-called independent state legislature doctrine, which argued that congressional maps drawn by legislatures (as well as other state statutes regulating federal elections) should not be subject to any review by state courts. But the decision, which was authored by Roberts, again, still kept open the possibility that it may intervene if state courts “transgress the ordinary bounds of judicial review.”

State courts trying to stop partisan gerrymandering may feel some trepidation about stepping over this ambiguous line. After all, here was the same justice who told them in Rucho to look at their own state constitutions and statutes, now warning them in Moore that he may stop them even if they ground their rulings on state law. Roberts hollowed out his own promise, restricting with one hand what he had invited with the other.