Last June, the Supreme Court stunned observers by forcing Alabama Republicans to redraw their state’s congressional map to create a second majority-Black district, thus passing on its latest opportunity to hack away at the very concept of multiracial democracy. Alabama is a little more than a quarter Black, but proposed map in Allen v. Milligan had included only one majority-Black district out of seven. In Alabama, where voting is so racially polarized that no Black candidate has ever won a majority-white congressional district, the lines on this map functioned as a bureaucratic denial of Black Alabamians’ right to vote.

In January 2022, a federal district court tossed the map as a cut-and-dry violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and ordered lawmakers to create one that included a second majority-Black district or something “quite close” to it. But those lawmakers, confident in the sympathies of the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority, promptly appealed. About a month later, the Court voted 5-4 to take up the case and blocked the lower court’s injunction in the meantime, allowing the illegal map to take effect for the 2022 midterm elections. The three liberal justices dissented, along with Chief Justice John Roberts.

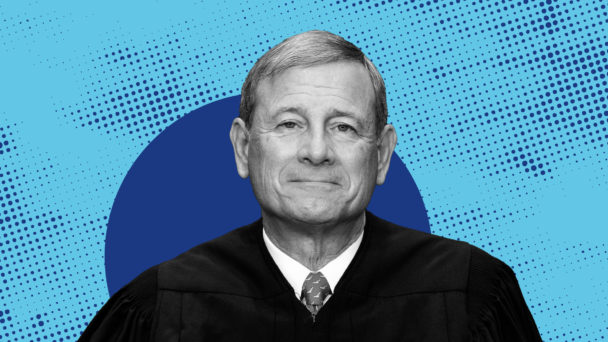

When the Court handed down its opinion in Milligan more than a year later, the vote was again 5-4, but with a different majority: Writing for himself, the three liberals, and now Justice Brett Kavanaugh, Chief Justice John Roberts—hardly a voting rights enthusiast—wrote that the district court had “faithfully applied” existing precedent, and that “no reason” existed to “disturb [its] careful factual findings” or “upset [its] legal conclusions.”

When you accidentally defend voting rights (Photo by Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images)

That the barest possible majority of justices suddenly decided they were unwilling to drown a statute the Court has spent decades dangling inches above the water’s surface felt equal parts genuinely surprising and vaguely farcical. Scrambling to make sense of the result, many pundits wondered if Roberts and Kavanaugh were bristling at the notion that they are mere tools of the Republican Party, and used Milligan to make clear that they would not rubber-stamp every brain-dead legal theory that every conservative troglodyte parades before them. In The Washington Post, Ruth Marcus hypothesized that Alabama had “overplayed its hand” by presenting such “aggressive arguments.” The opinion, wrote Amy Davidson Sorkin in The New Yorker, “suggested impatience with the maximalist demands that partisans on the right are placing on a Court they seem to feel they own.”

There was just one problem: Alabama Republicans decided not to give a shit. In July, they submitted a new map, this time with one majority-Black district and another that was 40 percent Black, a figure that astute readers will note is not “quite close” to 50.1 percent. The lower court, incensed, threw out that map, too, and turned line-drawing responsibilities over to a court-appointed special master, writing that it was “deeply troubled” by the defiance of Alabama lawmakers who “did not even nurture the ambition to provide the required remedy.” The legislature quickly appealed that decision to the Supreme Court—the same Supreme Court that saw “no reason” to side with them three short months ago.

Last week, a new report provided a hint as to why Alabama thinks it can snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. Per CNN’s Joan Biskupic—a reporter who is, let’s say, well-sourced on all things John Roberts—credit for Milligan’s “forceful affirmation” of the Voting Rights Act goes to Roberts, who spent months wooing Kavanaugh to join him in the majority. He succeeded, but barely: Although Kavanaugh signed off on the result, he conspicuously declined to join the part of Roberts’s opinion that narrowly affirmed the legitimacy of race-conscious legal remedies. And in a concurrence, Kavanaugh expressed sympathy for the proposition, espoused by the dissenters, that “race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future.” Since Alabama had not made that argument, he explained, he would not consider it “at this time.” In light of the state’s latest appeal, that time might be very soon.

Depending on how seriously you take the right of Black people to participate in democracy, this time around, the legal context for Milligan II might be materially different. As Biskupic notes, in since the Court decided Milligan, it also decided Students For Fair Admissions v. President & Fellows of Harvard College, in which Kavanaugh joined the conservative majority to end affirmative action at colleges and universities. In a concurring opinion in that case, Kavanaugh again voiced his skepticism of race-conscious legal remedies, like affirmative action, that extend “indefinitely into the future.” If you’re an Alabama lawmaker searching for a way over, under, or around your obligations under Milligan, that is a line you copy-paste directly into the brief urging him to change his mind.

That is, more or less, what Alabama’s lawyers are doing now. On Monday, they asked the justices for an emergency stay of the lower court’s order, which blocked the (still-racist) replacement map from taking effect, until the Court hears their case. Their filing stitches together Kavanaugh’s “cannot extend indefinitely into the future” language from his Milligan concurrence and the Students For Fair Admissions majority opinion that he joined: “Just as this Court held that ‘race-based’ affirmative action in education ‘at some point’ has to ‘end,’ the same principle applies to affirmative action in redistricting,” they write.

The hint is not subtle: Alabama lawmakers are trying to assuage Kavanaugh’s (quite-reasonable) fear of being labeled a spineless flip-flopper by showing him that, at the very least, there exists some logical legal explanation that would allow him to change his mind on Milligan. They are also arguing that if he really means what Students For Fair Admission says, Kavanaugh might have no choice but to do so.

When you have much to think about (BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

Alabama’s lawyers are not the first ones to stage this performance for an audience of one. Already, Republicans elsewhere have treated Kavanaugh’s Milligan concurrence as an invitation to attack the result, arguing that under Students For Fair Admissions, even if race-based redistricting may once have been constitutional, that deadline has passed. In July, the Alabama Political Reporter reported that lawmakers developed their strategy of ignoring Milligan in part based on “intelligence” collected from “D.C. connections,” who believe Kavanaugh is “open” to revisiting the decision. If they are right, Milligan would be less a vindication of the Voting Rights Act than a brief, inconsequential reprieve for it.

Of course, the fact that a handful of wishcasting morons in the Alabama legislature think Brett Kavanaugh is persuadable does not mean that Brett Kavanaugh is in fact persuadable. No justice cares more about being perceived, at least by members of the editorial boards of his favorite newspapers, as the Decent Reasonable Conservative. And as Mark Joseph Stern points out at Slate, Kavanaugh has publicly held out the result in Milligan as proof that the justices are not, contrary to popular belief, a bunch of partisan hacks—a conclusion that his second about-face in as many years would weaken considerably.

Yet even if the sequel to Milligan ends like the original, its very existence is remarkable—the output of a legal system that is so captured by conservative interests that the occasional conservative lawyer who happens to lose perceives no real cost to shrugging, sprinkling a few fresh citations into lightly-repackaged arguments, and trying again. (It’s not like, say, Sam Alito is going to be so incensed by Alabama’s disobedience that he signs on to a soaring tribute to the importance of protecting voters of color.) In July, when Republicans unveiled their still-obviously-illegal map, Alabama House Speaker and renowned math expert Nathaniel Ledbetter crowed that since Milligan was a 5-4 decision, “there’s just one judge that needed to see something different.” How “different” that something actually is doesn’t really matter. If Brett Kavanaugh is the only vote you need, and he left the door even the tiniest bit ajar, why not see if you can come back a couple months later and blow it all the way open?

The conservative justices, keenly aware of the need to downplay the significance of their dominance of the Court, are fond of publicly arguing that the institution is neither partisan nor ideological. Alabama’s gleeful scorn for the result in Milligan lays bare the cynical, hollow nature of these appeals. Whatever the justices say they are or imagine themselves to be, Republican activists are willing to bet on their loyalty to the conservative legal movement, further crowding a docket that is already stuffed with vehicles for pushing the law to the right.

They won’t win every time. They may not get everything they want, or exactly when they want it. But in a Supreme Court controlled by Republicans, the Republican Party’s losses will be rare, inconsequential, and temporary.