Late last month, Arizona lawmakers considered a piece of legislation that would typically put even the most ardent floor proceedings enthusiast to sleep: House Joint Resolution 2002, which would direct the Arizona Historical Advisory Commission to oversee the construction of a statue honoring the late Sandra Day O’Connor, who served as the Arizona Senate’s first woman majority leader—and, later, as the U.S. Supreme Court’s first woman justice.

“Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was a quintessential westerner and Arizonan with a longstanding reputation for intelligence, fairness, compromise and bringing people together,” it reads. “Her legacy has been a source of inspiration to Arizonans and Americans.”

A practical challenge for a proposal like this one, however, is that for many Republican politicians, the mere prospect of honoring O’Connor—a lifelong Republican who had the temerity to sometimes come down to the left of Antonin Scalia on the ideological spectrum—is now tantamount to heresy.

“Sandra Day O’Connor was a member of this legislature, and by all accounts a pretty good one. And then she became a U.S. Supreme Court justice,” said Rep. Alexander Kolodin, who cited “affirmative action and the prolonging of Roe’s terribly unconstitutional precedent” as among the more tragic results of O’Connor’s 25-year tenure. Kolodin, a lawyer who was recently sanctioned by the state bar for his role in Donald Trump’s post-election “Kraken” litigation, concluded as follows: “We cannot allow the distinguished members of this body to have to suffer walking by such an undistinguished jurist when they enter here in the morning.”

Set aside, for a moment, the fact that the statue would have gone to the U.S. Capitol in Washington D.C., thus sparing Kolodin from having to gaze upon it during his daily commute. Among Arizona Republicans, a moderate conservative justice who was appointed by President Ronald Reagan is, in 2024, officially Too Woke to merit posthumous recognition.

Less theatrical but just as dubious was Rep. Neal Carter, also a Republican, who explained his objections to the proposal by relating a story from his time in law school—a “pretty good,” “top-five” law school, he said—some 15 years earlier.

“We had a number of Supreme Court justices who came to speak to us—over the term that I was there, no less than three…different then-sitting Supreme Court justices. And I used to go and hear them,” Carter recalled. “I remember one of them, that I will not name—a then-sitting Supreme Court justice—who declared that Sandra Day O’Connor was the ‘worst thing that happened to the federal bench,’ end-quote.”

“A direct quote,” Carter said a second time. Kolodin, seated behind him, pounded the desk when Carter delivered the punchline.

I do not particularly care about statues, much less statues of a person who is largely responsible for the phrase “President George W. Bush.” That said, anytime an elected official publicly asserts that an anonymous Supreme Court justice was once contemptuous enough of an erstwhile colleague’s legacy to insult her in front of a group of law students, I am going to try and find out if the story is at all real—and, if so, which justice (allegedly) said it.

When I first saw Carter’s quote, I was, let’s say, skeptical. Among Supreme Court justices, who are quick to assure the public that they function as one big happy jurisprudential family despite their disagreements, proclaiming a colleague to be the “worst thing to happen to the federal bench” is the equivalent of a profanity-laced tirade that culminates in physical violence. This is no less true about retired justices; if word were to get out today that, say, Clarence Thomas had taken to calling Anthony Kennedy, who stepped down in 2018, a “pompous dunce with no redeeming qualities,” I promise it would generate a fresh round of headlines bemoaning the Court’s descent into undignified chaos.

Carter, whose priorities in office include fighting “disastrous leftist social policies,” is one of two representatives for House District 8, a suburban district near Phoenix. He was appointed in 2021 by the Pinal County Board of Supervisors to replace an incumbent who died in office, and he won reelection to a full term in 2022. Carter graduated from UCLA in 2006, and from NYU School of Law—a perennial top-five law school—in January 2010. This means he was on campus for a three-and-a-half-year period beginning in the fall of 2006, about a year after O’Connor retired and Justice Samuel Alito took her place.

With this approximate timeline in mind, I called Carter last week to ask for comment for this story. He was glad to elaborate—up to a point.

O’Connor poses in front of the Court shortly after being sworn in, September 25, 1981 (Photo by David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images)

Carter was en route to the Arizona Capitol when we spoke, and he dropped a few more hints along the way: He referred to the mystery justice using male pronouns, and explained that he interpreted the comment as a reference to the sentiment that O’Connor’s “decisions were not consistent.” He especially took issue with her failure to vote to overturn Roe v. Wade, which, he argued, exacerbated the politicization of Supreme Court confirmation fights that continues to this day.

“O’Connor was appointed by Reagan with the understanding, I think, that she would vote to rectify their incorrect decision,” Carter told me. “She had an opportunity to, and she didn’t.” When they finally overruled Roe in 2022, he said, the justices were “acknowledging that they were incorrect, just like they acknowledged with Dred Scott that they were incorrect.”

Carter also revealed that the mystery justice’s comments came at an event put on by the Federalist Society; Carter was vice president of the chapter at NYU for a time. However, he declined to identify the justice when I asked, explaining that he would “consider it a breach of trust” even all these years later. “The people [who] share something like that with you, they don’t want it showing up in the news,” Carter said. “And the whole idea of having a FedSoc event like that kind of thing is exactly so you can talk to Supreme Court justices.” (That a sitting justice felt comfortable enough to sit in a room full of twentysomethings he just met and caricature a recently-retired colleague as a spineless RINO is perhaps something to remember next time a tut-tutting law professor tells you that the Federalist Society is merely a nonpartisan debate club.)

Since visits from Supreme Court justices are the sort of thing that law schools typically document to include in glossy fundraising mailers, I turned next to the archives of NYU’s official magazine. I found write-ups of three justices who made official visits to campus during this period: Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg spoke at an October 2006 event commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Brennan Center for Justice, and again in May 2008 for the 50th anniversary of a civil liberties fellowship. In 2007, Justice Stephen Breyer spoke to the student editors of the Annual Survey of American Law, who dedicated that year’s edition to him. In April 2009, Alito presided over the 37th annual Marden Moot Court Competition, after which he praised the participants for keeping their cool under pressure. “We wanted to give you a workout, and I think we did,” he told them.

I also reviewed back issues of The Commentator, NYU Law’s student newspaper. In 2008, O’Connor herself gave an address about, of all things, “the state of judicial independence in American courtrooms.” Otherwise, the archives contained nothing related to my search, although I did find the recap of Pro Boner’s hard-fought victory over Minimum Contacts in the 2006 intramural flag football championship game to be compelling stuff.

The NYU FedSoc chapter’s online footprint was another dead end. Its YouTube channel posted three videos nine years ago and nothing since. Its Facebook group dates to 2013. There is a blog, but alas, the earliest entry is from 2011. I sent emails to NYU Law addresses listed for the student group and its current chapter president, but did not receive a response.

Screencap via NYU Law Magazine

Regrettably, I do not think the record, such as it is, is very useful in narrowing the field, because Carter’s telling suggests that this particular tranche of events—intimate conversations with leading lights of the conservative legal movement—was far less public than school-sponsored black-tie dinners. In our conversation, Carter described several other experiences that go unmentioned in contemporaneous school publications: Again through Federalist Society connections, he got to meet with a justice “that RVs,” for example, and visit the home of Bush-era solicitor general Ted Olson. Carter also remembered a sit-down with failed Reagan Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork, which he described as “really nice.”

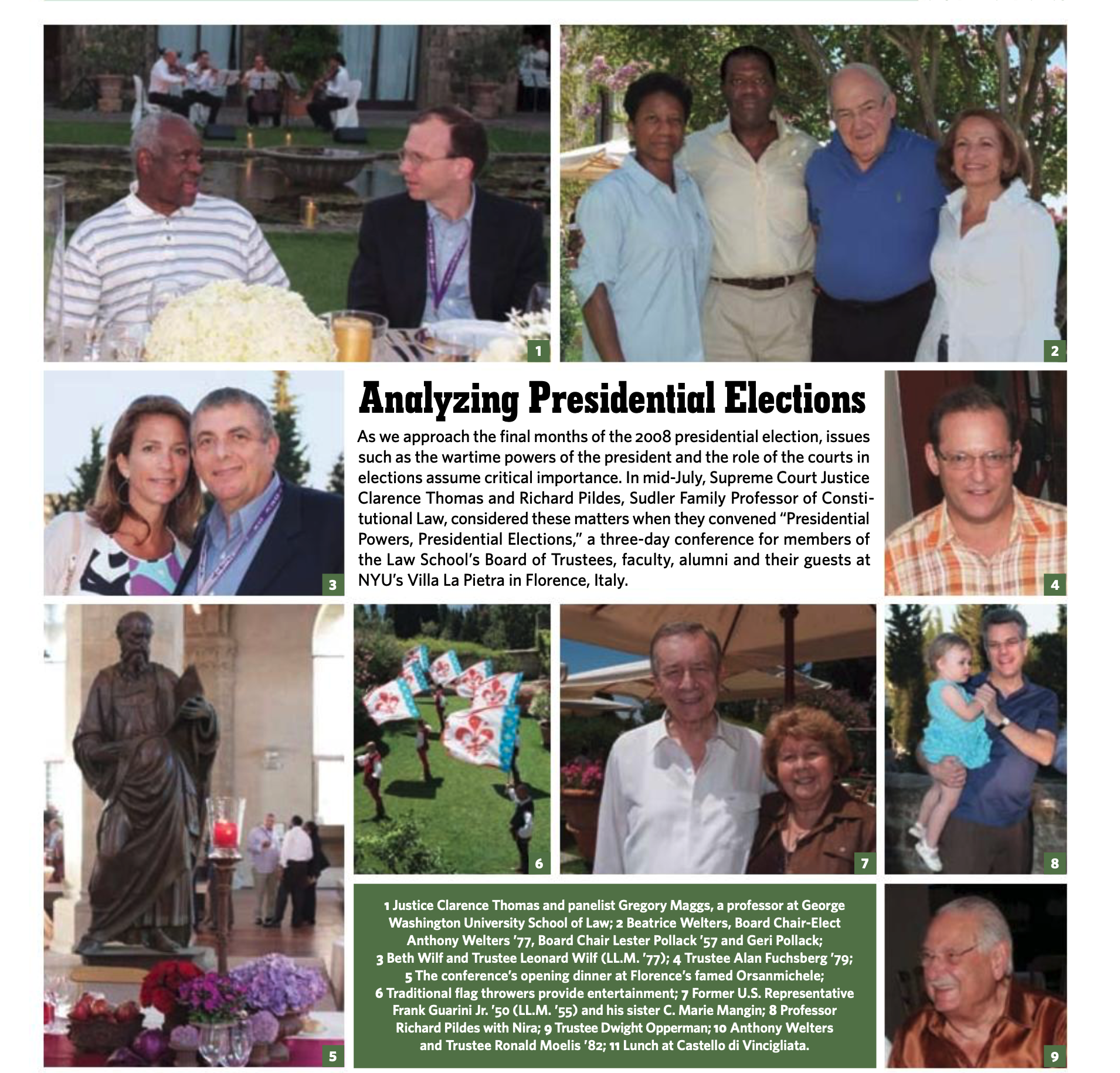

I assume a justice “that RVs” has to be Clarence Thomas, whose fondness for creative luxury motorcoach financing is a matter of public record. But the only mention I can find of Thomas-NYU interaction during this period is a July 2008 conference on presidential powers that Thomas co-hosted at (prepare to be shocked) Villa La Pietra, an NYU-affiliated renaissance villa in Tuscany. An Italian resort doesn’t seem consistent with the more informal scenes Carter describes, and it was also designated as open to law school trustees, faculty, alumni, and their guests, which would rule out lowly tuition-paying students.

Last week, I reached out to NYU Law to ask about their records of campus visits by Supreme Court justices during this time. A media relations representative replied with a few clarifying questions, but did not follow up. I will update this post if they respond. If you know of an event I missed, please reach out.

In the meantime, process of elimination can help a little here. The use of male pronouns would rule out Ginsburg and Sotomayor. The description of the setting probably rules out the liberal male justices, Stephen Breyer, David Souter, and John Paul Stevens, none of whom seem like the type to let it rip in an off-the-record FedSoc bull session. Of the remaining justices, John Roberts and Anthony Kennedy, whose occasional departures from conservative orthodoxy have sparked criticism from the right, feel less likely to excoriate O’Connor for the same sin. Kennedy, for example, joined O’Connor in Planned Parenthood v. Casey to weaken-yet-preserve Roe, a betrayal that still peeves many Republicans three decades later.

This leaves Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito, the era’s three most strident ideologues by a good measure. We know Alito and probably Thomas, at least, paid visits to campus during the period in question—Alito at moot court in 2009, and Thomas at some below-the-radar FedSoc event to shoot the shit about road trips. Scalia was famously at NYU a little earlier, in 2005, when a gay NYU law student who’d won a lottery for a seat at a limited-seating, closed-to-the-press event asked the justice to explain his 2003 vote in Lawrence v. Texas to sustain state efforts to criminalize consensual sodomy—and, after that, a follow-up about whether Scalia sodomized his wife. (Scalia found the question “unworthy of an answer.”)

All three justices would have had plenty of reasons to grumble about O’Connor at the time. Her vote helped relegate Thomas and Scalia to the dissents in cases like Casey, Lawrence, and Grutter v. Bollinger, in which the Court upheld a watered-down version of affirmative action in 2003. Acrimony between O’Connor and Scalia, especially early in their tenures, was dependable fodder for dishy books written by plugged-in legal journalists. In 1989, citing sources close to the Court, the Washington Post described Scalia as growing “impatient with O’Connor’s sensitivity to political pressure,” although it also noted that “more often than not, she usually joins him on the court’s new conservative majority.”

O’Connor and Scalia greet lawmakers before a House Appropriations Subcommittee meeting, May 7, 1992 (Photo by Laura Patterson/CQ Roll Call via Getty Images)

Alito did not serve with O’Connor, but their legal careers were nonetheless intertwined. In a 1985 application to work in Reagan’s Department of Justice, Alito wrote that he was “particularly proud” of his work on cases arguing that “racial and ethnic quotas should not be allowed,” and that “the Constitution does not protect a right to abortion”—two propositions that O’Connor considered and rejected. As a federal appeals court judge, Alito had sought to uphold the Pennsylvania abortion restrictions at issue in Casey, a gambit that made him “a mini-hero of the far-right in the abortion battles,” as Emily Bazelon wrote for Slate in 2005. In their Casey opinion, O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter went out of their way to reject key aspects of Alito’s argument, much to the frustration of reactionaries everywhere. In the years after Alito replaced her, O’Connor was reportedly “furious” about his efforts to push the law to the right, and described him as an “aloof” person with “no sense of humor.”

It was not until 2022 that Alito finally prevailed, in a sense, writing the opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that overruled Roe and Casey—cases, Alito wrote, that had “enflamed debate and deepened division.” He also joined the majority in Students For Fair Admissions v. Harvard last year, hollowing out Grutter and banning affirmative action 20 years after O’Connor voted to save it. Given that Alito’s most significant accomplishments on the Court involve shoving his predecessor’s legacy through a jurisprudential paper shredder, it seems reasonable to conclude that 15ish years ago, he would have been fluent in using caustic adjectives to describe O’Connor’s greatest hits.

One more wrinkle: In his speech on the House floor, Carter described the mystery man in particular and the three justices he remembers visiting campus as “then-sitting.” In the context of the commenting justice, it’s not clear if this designation meant only that the justice was sitting at the time, which would be true of all three prime suspects, or if it signals that the justice is no longer sitting today, which is true only of Scalia, who died in 2016. But Carter declined to give any more clues, particularly since the pool of candidates is small enough as it is. “There’s really so many guesses. I mean, come on,” he said before we hung up. “It can only be one of four people, or something, from that timeframe.”

Alito looks on during a press conference shortly after his nomination to the Court, October 31, 2005 (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

I reached out to the Supreme Court’s public information office to ask the living justices if they made the comments Carter described, but did not receive a response. Carter offered to try and think of names of former Federalist Society members who could confirm his story, but did not get back to me with any, and did not respond to multiple follow-up text messages. I independently contacted several people who were members of NYU’s Federalist Society chapter at the time, none of whom claimed to have any recollection of a story like Carter’s. (More than one said something to the effect of, “If I had heard something like that, I probably would have remembered it.”) For now, then, your educated guess about who said what is as good as mine.

At this point, the stakes of this whodunit are low even by the standards of Supreme Court-adjacent gossip. O’Connor passed away in December at age 93, almost two decades after stepping down from the bench. Scalia is dead, and neither Thomas nor Alito care about criticism that doesn’t come from their favorite Newsmax personalities. But for an increasingly unpopular, sharply polarized institution whose members keep gritting their teeth and insisting that the Court is this magical bastion of nonpartisan gentility, confirming the details of the story might be, at the very least, a little embarrassing. As it turns out, life-tenured judges are as capable as any co-workers anywhere of hating each other’s guts.

Fortunately for the offending justice, the warm embrace of the conservative legal movement shields them from even this rough approximation of accountability. In just about any semi-public setting, for a Supreme Court justice, calling a colleague the “worst thing to happen to the federal bench” would be a wild breach of decorum, laying bare the bitter divisions that justices across the ideological spectrum still pretend do not exist. But in the cloistered world of Federalist Society networking events at elite law schools, it was just a conservative legal movement celebrity chopping it up with friends, frankly discussing what everyone in the room understood to be an embarrassing failure—a failure which, with any luck, they would one day have the privilege of voting to make right.