The recent flood of Supreme Court ethical misadventures has scandalized many Americans, but it hasn’t stopped the Court’s conservative supermajority from plowing ahead with its right-wing agenda. Earlier this month, it decided to take up Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, a case that gives the justices the chance to get rid of what’s known as Chevron deference once and for all. This result would be a catastrophic blow to Americans’ ability to regulate the economy, protect themselves from harm, and otherwise govern society as they see fit.

The doctrine, which takes its name from a 1984 decision Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, essentially says that federal agencies, not federal judges, get to interpret congressional delegations of authority to executive agencies. Agencies issue rules under broad mandates from Congress, which passes laws that set a general goal—clean up the air, for instance—and charge agencies with determining how best to fulfill it.

Under Chevron, courts are generally obligated to defer to these determinations, which are often very technical and come from subject matter experts; without it, these determinations would be subject to the approval of the judiciary, allowing the Court to strike down regulations it doesn’t like. The conservative legal movement has long sought to overturn Chevron, which underpins much of the pesky Big Government regulation that Republican politicians always complain about. Given the Court’s current composition, which includes multiple justices who have spoken and written against Chevron in the past, the clean air regulations that would go down first are those that keep acid rain from falling on our heads.

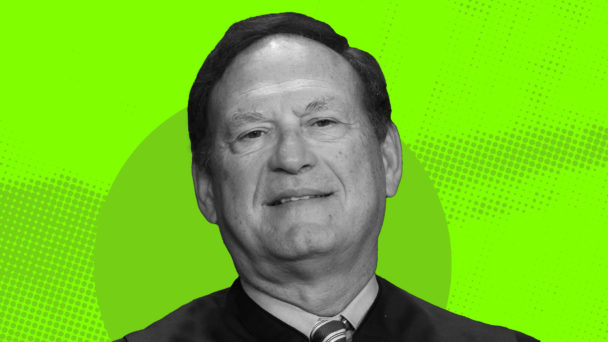

When you hear someone suggest seatbelt laws are actually unconstitutional (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

To be clear, conservative judges have already done yeoman’s work to undermine Chevron: Over the last several years, the Court has found clever ways to invalidate several of the federal government’s attempts to fight the coronavirus pandemic, including a workplace vaccination mandate and a federal eviction moratorium.But the fight against Chevron is only the legal front in a broader war on the institutions of modern society. The purpose of the contemporary state is to offer people protection: from airborne pollutants through regulations that make the air clean, from workplace injuries through rules that make job sites safer, from extreme poverty and illness through the welfare state, and so on. (Some of these regimes are more effective than others, but you get the idea.)

Conservatives have split up the task of trying to tear down this protection. Legislators enact tax cuts that starve the government of funding, shrink the budgets of vital agencies, and maintain the decades-old dream of destroying Social Security. Courts do the more insidious work of attacking the rules that make the system work: They gut environmental protections, attack safety standards, and generally make it harder for Americans to protect each other in the workplace, the home, and the world at large.

Consider how the end of Chevron might affect education policy. Many contemporary fights over K-12 education center on charter schools, which attract broad support from the right but heavy opposition from liberals and teachers’ unions, who argue that charters employ weaker teacher training and qualification standards while siphoning money away from traditional public schools. Under current law, the federal government provides grants to charter schools, which are administered by the Department of Education—subject to standards it creates and enforces to ensure that the charter schools it funds are “high-quality.”

If judges get rid of these standards in a post-Chevron world, many barriers to opening a charter could disappear. Profit seekers and grifters could open charter schools that couldn’t meet current standards, taking advantage of federal funds available to them for the first time. This proliferation of new schools would, of course, spur conservative demands for greater funding. A post-Chevron judiciary could work in concert with conservative legislators to provoke a virtuous cycle for the charter school ecosystem and a vicious one for the public schools they are ‘competing’ with. Public education is one of America’s few remaining shared social institutions. Without Chevron, it will get a little weaker.

Environmental regulations, long a target for businesses, would also be in jeopardy without Chevron. Republican legislators are perfectly happy to extend tax cuts to miners, manufacturers, and other major polluters. But they’ve never repealed the Clean Air Act or Clean Water Act, both of which are sources of great annoyance and expense to industry. Lawmakers don’t do so because these laws are popular; people like to know that the air they’re breathing is clean, and that the water they’re giving their children is safe to drink.

But most of the actual rules governing what goes into our air and water aren’t found in legislation, but instead in regulations issued by the EPA. By overturning Chevron, the court would give itself a veto on most of these rules. For instance, the Clean Air Act empowers the EPA to decide which atmospheric pollutants are most harmful to human health, and to come up with a plan to limit their presence. Absent Chevron, the courts could overrule the EPA’s decisions about what level of harmful toxins counts as too much.

Because Congress has been unwilling to pass substantive gun safety legislation, executive action has been the core of the national response to gun violence. But federal appeals courts are divided on whether Chevron applies to rules with criminal penalties—including, for example, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms’s bump-stock rule, which banned the accessory in response to a mass shooting in October 2017. If the Court further undermines the executive’s ability to interpret federal gun laws, worried citizens will see no federal response to this country’s epidemic of mass shootings.

The end of Chevron would be a massive victory for the right’s broader attack on the collective institutions of American life, the purpose of which is to leave people isolated, angry, and afraid—concerned only for their own welfare, and skeptical that things could ever be better. Surrounded by shoddier schools, deadlier guns, more dangerous machinery, and deadlier toxins—who could blame the average person for thinking their government had abandoned them? A Fox News host neatly summarized this ethos after a recent mass shooting, when he suggested that the way to protect yourself is to be prepared to kill anyone you meet.

Fox News’s advice for life in America: “Have a plan to kill everyone you meet” pic.twitter.com/MaOE6WfIyh

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) May 7, 2023

Conservatives often argue that ending Chevron would return lawmaking where it belongs—to Congress. But the idea of 535 people making all the most important rules in a massive, modern, industrial economy is ludicrous—especially given how unexceptional and unqualified many of those 535 people are to the task. Congress’s slow pace of work and lack of expertise would combine to produce much less and much lower-quality regulation on all sorts of things—regulation that voters, speaking through their elected leaders, have said they want. Reversing Chevron wouldn’t strengthen self-government. It would make self-government practically impossible.

The Chevron Court understood that Congress lacks the time, talent, and capacity to do the nitty-gritty work of running a modern society, and thus entrusted agencies to fill in the gaps. Conservatives don’t really care about where the rules come from, though—they just want fewer of them. The end goal is a deeply fractured society in which normal people never have the chance to form the solidarity necessary to fight existing hierarchies, and the wealthy and powerful can act without fear of consequence.