When voters in California, Colorado, and Hawaii go to the polls on Tuesday, they’ll have the opportunity to amend their state constitutions to protect same-sex couples’ right to marry.

As you may be aware, the federal Constitution has protected marriage equality for almost a decade now. But advocates for LGBTQ rights fear that federal constitutional rights aren’t worth much these days: Abortion was a protected right under the Constitution, too, until the Republican justices on the Supreme Court declared otherwise. Since residents of these three states can’t trust the Supreme Court to follow its own precedent, they’re taking their rights into their own hands by putting marriage equality on the ballot.

In 2015, the Supreme Court recognized for the first time that marriage is a fundamental right, and held in Obergefell v. Hodges that denying that right to same-sex couples violates the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. Opponents of marriage equality argued that courts must analyze constitutional rights by conducting an exacting inquiry into history and tradition. But the Court adopted a broader view. In his opinion for the Court, Justice Anthony Kennedy said that the justices should be guided by history “without allowing the past alone to rule the present,” and acknowledged that “the nature of injustice is that we may not always see it in our own times.” In other words, perhaps “this is how the country did things before” is not a great metric for constitutionality in a country that’s done a lot of messed-up shit.

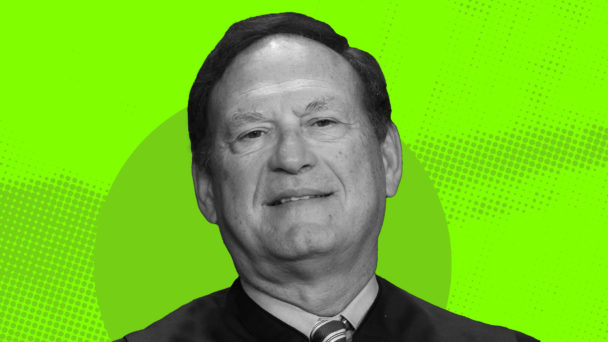

In Dobbs, the Supreme Court abandoned that reasoning. In his majority opinion, Justice Samuel Alito wrote that “a right to abortion is not deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions,” and treated that as fatal to a claim to a substantive right under the Due Process Clause. In a concurring opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas went even further, urging his colleagues to “reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents” and explicitly identifying Obergefell as a case ripe for reversal. Earlier this year, Alito re-upped his complaints about the alleged “danger” created by Obergefell—“namely, that Americans who do not hide their adherence to traditional religious beliefs about homosexual conduct will be labeled as bigots and treated as such by the government.”

The reversal of Roe, the rise of the conservative legal movement’s history-and-tradition test, and two justices’ open disdain for Obergefell all point to a precedent at risk. And like most states, California, Colorado, and Hawaii still have defunct laws on the books that ban (or authorize the state legislature to ban) same-sex marriage. Obergefell made those laws inoperative, but if the Court were to overrule it, those zombie laws would come back to life.

When someone says you’re being bigoted even though you’re being bigoted (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

California’s proposed constitutional amendment, Proposition 3, would repeal language in the state constitution that describes marriage as only between a man and woman, and make marriage a fundamental right. Members of the state’s Senate Judiciary Committee published an analysis of the legislation that explicitly says this proposal is a response to the Supreme Court: Proposition 3 is necessary “not because the reasoning underlying Obergefell and marriage equality is dubious or unclear on the issue, but because Courts can change,” they write. “And in fact, the United States Supreme Court already has.”

Colorado’s proposed amendment would similarly strike language in its state constitution providing that “only a union of one man and one woman shall be valid or recognized as a marriage in this state.” Here too, the Supreme Court loomed over the campaign to remove the ban. “More than one Justice has said that same-sex marriage should be revisited,” said Nadine Bridges, executive director of the LGBTQ+ advocacy organization One Colorado, at an event with state lawmakers earlier this year. “If the Obergefell decision is overturned, same-sex couples cannot be married in the future here in Colorado if this amendment remains in our state constitution,” she said. “That’s why we’re giving you all the chance to fix this wrong.”

Hawaii law doesn’t ban same-sex marriage, but the legislature does have the power to restrict marriage to different-sex couples. The state’s proposed constitutional amendment would repeal that grant of authority. And again, the Supreme Court is the cause. “I’ve watched as this ultraconservative court has stripped away our right to make decisions about our own bodies, rolled back the clock on voting rights, affirmative action, and the ability of states to limit gun violence,” Rep. Jill Tokuda said earlier this year. “We cannot stand by and hope the U.S. Supreme Court does nothing.”

California, Colorado, and Hawaii show that the popular backlash to the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs extends beyond the fight to preserve abortion rights. The residents of the states are justifiably distrustful of the Supreme Court’s commitment to all sorts of civil rights. And in the absence of help from the federal courts, they’re doing their best to help themselves.