Two years ago, voters in Wisconsin flipped control of their state’s supreme court, yielding the court’s first 4–3 liberal majority since 2008. That majority wasted no time delivering for the people of the state: In less than two years, the Court has struck down intensely gerrymandered legislative maps, giving Democrats a fair shot at winning elections in a purple state; stood up for working people’s right to access the basic social safety net; and made absentee voting easier. It may not be a big majority, but it’s been enough to undo years of democratic backsliding in Wisconsin while simultaneously pushing the state towards a bit more justice for ordinary people.

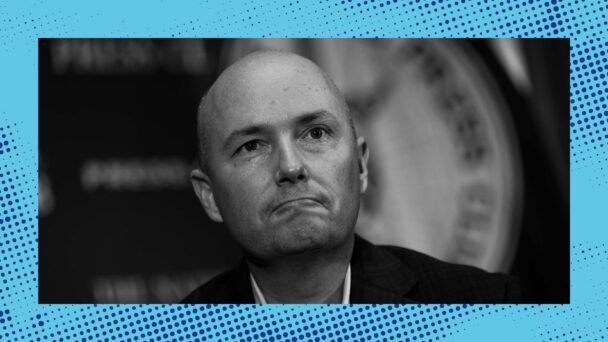

On April 1, however, the Court’s ideological majority will be back up for grabs. After 30 years on the Supreme Court, Justice Ann Walsh Bradley, a liberal, is not seeking re-election. The race to succeed her is between the former Republican Attorney General of Wisconsin, Brad Schimel, and Dane County Judge Susan Crawford, a former prosecutor who has been endorsed by all of the current liberal justices. And while Crawford is explicitly running to continue building on the progress of the last two years, Schimel’s campaign website describes the current jurisprudence as “dramatic overreach…leading our state to destruction.” This isn’t a race about slightly different methods of interpreting a few arcane laws that don’t have much real-world impact. It’s a race that will determine whose rights, whose votes, and whose freedom matters in the state of Wisconsin.

If the significance of the race wasn’t already clear from the differences between the two candidates, the amount of money spent in the race is a fairly telling sign of how interested parties are understanding the race’s impact. By the time all is said and done, the race is expected to see over $100 million in spending, breaking the record for spending in a judicial election—a record set in 2023, the last time Wisconsin elected a Supreme Court justice. So far, some $12 million of that spending has come from Elon Musk and his political groups. It is about as high-profile—and high-stakes—as a state Supreme Court race can get.

(Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Like many states, Wisconsin elects its Supreme Court justices through ostensibly non-partisan elections. However, in a politically divided state in which Democrats control the governorship and Republicans control both chambers of the state legislature, the Supreme Court often tips the balance of power. Although Crawford won’t be listed as a Democrat on the ballot, she’s been endorsed by unions, Planned Parenthood, EMILYs List, Wisconsin Conservation Voters, and other progressive organizations, and her campaign has raised millions of dollars from the Democratic Party and liberal billionaires J.B. Pritzker and George Soros. Schimel, by contrast, has raised his money from the Republican Party and the likes of billionaire Dick Uihlein, in addition to Musk and his allies; he’s been endorsed by Donald Trump, Jr., conservative activist Charlie Kirk, and President Donald Trump himself, among others. For a non-partisan race, it’s feeling decidedly partisan.

This is perhaps not surprising. Wisconsin has been at the center of the political universe for years. In 2010, the state attracted national attention when then-Governor Scott Walker, a Republican, effectively ended collective bargaining rights for public-sector employees following months of mass protests. After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and ended the constitutional right to abortion, abortion became briefly inaccessible in the state due to an 1849 ban on the procedure. The extent of Republican gerrymandering in the state—prior to the recent Wisconsin Supreme Court decision—has caused people to call into question whether Wisconsin can truly be considered a democracy. And, of course, no presidential election can take place without Wisconsin in a place of honor as one of the few remaining true swing states.

That every political issue in the United States eventually becomes a judicial question is certainly true in Wisconsin. A state court recently found Act 10, Walker’s attack on public-sector unions, to be largely unconstitutional in a lawsuit that is almost certain to reach the state Supreme Court. Following litigation, the abortion ban is no longer being enforced for now, and an opinion on its validity is expected from the state Supreme Court this spring. The Supreme Court’s December 2023 ruling on Wisconsin’s legislative maps found that they were illegally gerrymandered, and ordered new, fairer maps to be drawn ahead of the next election cycle. As a result, at least for now, there are actually competitive state legislative races in which the Democrats have a shot at winning a majority of seats when they win a majority of votes. On every one of the most salient political issues facing the state, the Supreme Court has played a critical role in deciding the outcome.

Between now and the end of the decade, the state will see four more Supreme Court elections, one in each of the next four years. If Schimel wins the election, control of the court will be on the ballot again in 2026 and possibly 2027, both years in which conservative justices will have to defend their seats. But if Crawford wins, the liberal majority should be safe until at least 2028, the next time a liberal justice would be up for re-election. A secure liberal majority could turn down the temperature in the next few elections, and might even make it possible to have a judicial election spending record last longer than one election cycle.

Regardless of the outcome of this election, a system in which billionaires pour their fortunes into electing judges with all-but-explicit partisan affiliations—and in which individual state supreme court justice elections determine things like “whether women have fundamental rights” and “if Wisconsin remains a democracy”—isn’t exactly ideal. State judiciaries are just as much victims of our failing democracy as they are its potential champions. Oligarchs like Elon Musk are committed to buying their own legal system, or tearing it down when they can’t. Getting to a point where state courts reliably serve the people without the interference of billionaires and their allies is going to take generations of hard work, and certainly won’t be solved in one election.

In the meantime, however, the high-profile and partisan nature of these races isn’t necessarily a bad thing. If voters are expected to elect their judges, elections shouldn’t force voters to parse through unintelligible abstractions about originalism or whatever else. Instead, they should be about what the candidates intend to do with the power of the offices they seek, so that people know exactly what they’re getting with their vote.