To a first-time reader, the Constitution is a criminal defendant’s dream. The Bill of Rights, which spells out most of the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution, spends half its text protecting people from criminal investigations and prosecutions. The Sixth and Eighth Amendments promise, among other things, that defendants will receive a “speedy and public” jury trial, won’t be held on “excessive bail” or forced to pay “excessive fines,” and cannot be subject to “cruel and unusual punishments.”

These amendments are radical documents. They recognize the inherent risk that the government will use criminal courts to oppress the poor or vulnerable minorities rather than to protect them—which is why the Supreme Court has spent decades reinterpreting these amendments such that they barely protect anyone from anything.

Take the Eighth Amendment. It forbids “cruel and unusual” punishments, which naturally raises the question of what punishments count as cruel and unusual. Over the years, the Court has determined that this provision prevents the government from bringing back medieval torture techniques, limits how the government can impose the death penalty, and constrains how severely it can punish people for crimes they commit as children. What it doesn’t do, however, is give adults any protection at all against excessive prison sentences.

As crime rates increased during the 1980s, politicians following President Ronald Reagan’s lead won elections across the country by promising “law and order”: more police, more prisons, and harsher sentences. Liberal judges, they argued, were endangering the public by letting hardened criminals out of prison. Many jurisdictions rewrote their laws to give judges less discretion, to increase the overall length of sentences, and to impose harsh mandatory minimums for crimes they deemed especially heinous. When the most egregious of these sentences reached the Supreme Court, it gave a thumbs up to this era of limitless incarceration.

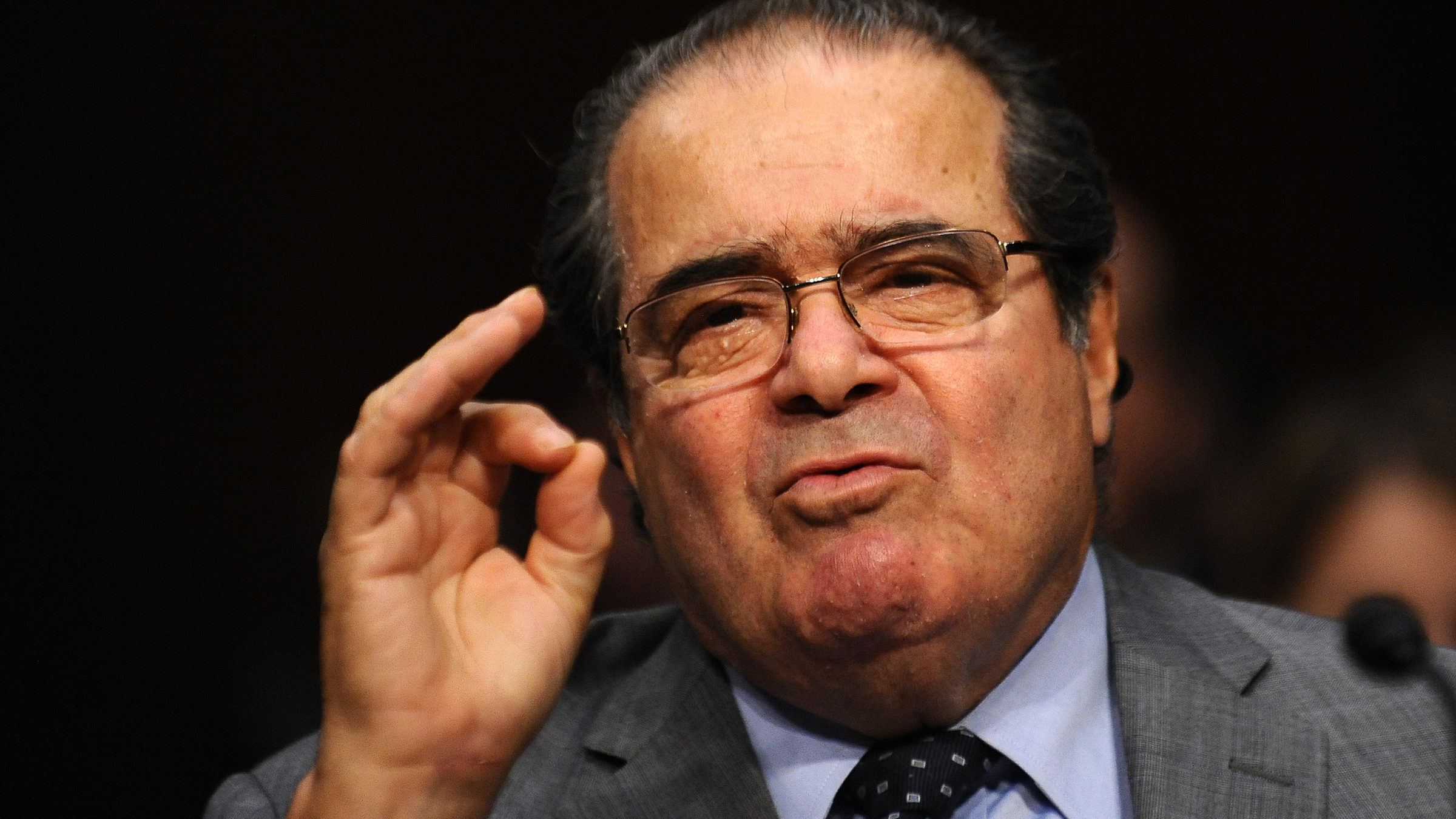

In 1990, Michigan sentenced Ronald Harmelin to life without the possibility of parole for his first felony conviction: possession of cocaine. A year later, the Supreme Court upheld his sentence by a 5-4 vote. Writing for the plurality in Harmelin v. Michigan, Justice Antonin Scalia went on a lengthy discussion of the so-called “Bloody Assizes” that followed the Duke of Monmouth’s 1685 revolt against King James II of England in order to determine how long the Constitution permits Ronald Harmelin to languish in prison because the cops found cocaine in the trunk of his car. Scalia concluded that because the Eighth Amendment bars “cruel and unusual” punishments, it bars “cruel methods of punishment that are not regularly or customarily employed.” In other words, as long as it’s common for the government to give people life sentences for contraband possession, then it might be cruel, but it isn’t unusual.

Antonin Scalia whenever he finds a particularly robust Wikipedia article on medieval criminal punishment techniques (JEWEL SAMAD/AFP via Getty Images)

Not to be outdone, California sent Gary Ewing to prison in 2000 after he was convicted of stealing three golf clubs. Under the state’s “three strikes” law, his prior convictions for burglary and robbery meant that this conviction carried a life sentence. The Court upheld his sentence, too, also 5-4. Writing for a three-justice plurality, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a Reagan appointee, left open the possibility that a disproportionately long sentence could violate the Eighth Amendment. But, she explained in Ewing v. California, if California decided his prior convictions rendered him “simply incapable of conforming to the norms of society,” its decision to permanently imprison him was a reasonable imposition on his constitutional rights.

If a bar on “cruel and unusual punishments” permits states to sentence recidivists to die in prison for shoplifting golf clubs, it’s hard to imagine what punishment would fail O’Connor’s standard. Worse yet, that standard probably doesn’t command five votes on today’s far more conservative Court; Justice Clarence Thomas, for example, wrote a concurrence asserting that the Eighth Amendment does not require proportional sentences at all.

You might think it’s crueler to send someone to prison for the rest of their life than it is to, say, flog them in the town square. Ronald Harmelin and Gary Ewing would probably agree. But the Court’s majority, like some of the country’s bloodthirstiest politicians, thinks automatic prison sentences are necessary to protect law-abiding citizens from people like Gary Ewing and Ronald Harmelin. Thus, an amendment written to restrain criminal courts has been interpreted only to forbid punishments so outlandish that no existing jurisdictions are trying to impose them, while simultaneously permitting the United States to incarcerate more people for longer sentences than just about anywhere else on earth.

At every turn, defendants are told they have a constitutional right to a jury trial, but the state will savagely punish them if they choose to exercise it.

Just as the Eighth Amendment’s vagueness allowed the Court to interpret it into oblivion, the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of a “speedy and public” trial helps only a tiny fraction of defendants today. In 1972, the Supreme Court in Barker v. Wingo laid out a multi-part balancing test for determining how much pretrial delay, exactly, is too much pretrial delay. Rather than setting a time limit, the court identified factors that might make a given delay more or less reasonable.

This read of the Sixth Amendment is, to strip the legal language away, a vibes-based approach. Critically, the Wingo standard permits the government to use problems of its own creation to excuse delayed trials; state governments can refuse to pay for enough judicial staff to manage the volume of prosecutions, for example, and then blame the delay on clogged dockets. If the courts reviewing these cases are sympathetic to the prosecution’s point of view, there’s little a defendant can do to defeat that presumption. Many states have enacted speedy trial statutes of their own, but defendants in states that haven’t are shit out of luck. Some state courts have blessed delays in excess of four years between arrest and trial as constitutionally unproblematic.

When protections against excessive sentences and pre-trial delay evaporate, the right to a trial by a jury all but disappears, too. Although every defendant has a right to a jury trial, fewer than ten percent actually invoke that right. Why would they? Accused people are routinely held in jail while they await trial, which takes months or years. While they sit in jail, they are told that if they go to trial and lose, they will be punished much more severely than if they just plead guilty. At every turn, defendants are told they have a constitutional right to a jury trial, but the state will savagely punish them if they choose to exercise it.

This logic wouldn’t apply to constitutional rights that modern conservative judges favor. The Supreme Court would not, for example, allow a state to force Mormons or Jehovah’s Witnesses to pay a special tax unless they “voluntarily” waive their right to freely exercise their religion. Nor would it accept a reading of the Second Amendment that applied only to flintlock muzzle-loaders in use in 1788. But unlike the framers, the conservative legal movement is fundamentally hostile to criminal defendants, which means the parts of the Constitution intended to protect them have been read out of existence.