On September 27, 1901, Filipino rebels won a decisive victory over occupying American forces at Balangiga, a small village on the island of Samar. Before the battle, Balangiga had been a bit of a backwater in the Philippines’ struggle for independence. That changed when two American soldiers attempted to molest a local girl. Fed up with the cruelty of the American forces, the Filipino townspeople rose up and annihilated the occupying garrison.

The colonizers responded swiftly and brutally. Two years after crushing Spanish forces in Manila, the United States had struggled to maintain its new holdings. The Filipinos’ victory at Balangiga, sensationalized in the American press, highlighted those struggles. Angered and embarrassed, Brigadier General Jacob Smith—commander of the American troops in the Philippines—ordered Major Littleton W. T. Waller to lead a contingent of soldiers across Samar.

“I want no prisoners,” Smith commanded. “I wish you to kill and burn; the more you kill and burn the better it will please me.”

Waller asked Smith for clarification.

“Kill everyone over ten,” Smith replied.

Over the next four and a half months, Waller’s forces slashed, burned, and murdered their way across Samar, killing an estimated 15,000 Filipinos. By the time the conflict ended in 1913, 200,000 Filipino civilians had died by slaughter, starvation, or disease.

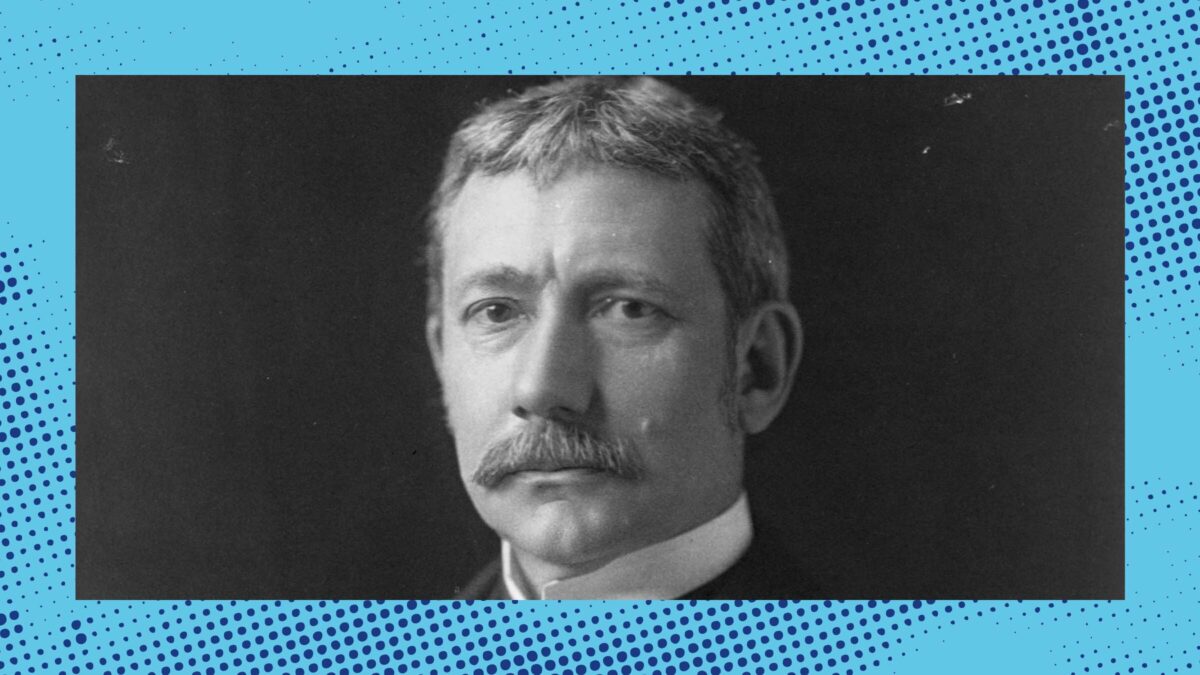

Waller’s march remains one of the worst atrocities ever committed by the United States military. But he and Smith were merely bit players in the new American Empire. The man in charge of subjugating the United States’ colonial possessions wasn’t a soldier at all, but a lawyer: New York City’s leading corporate attorney, Secretary of War Elihu Root. From his early years as a Manhattan trial lawyer to his time in the McKinley and Roosevelt Cabinets, Root zealously advocated for the interests of America’s Gilded Age Elites. He oppressed entire nations in the name of profit, with ramifications that linger to this day.

(Buyenlarge / Contributor / Getty Images)

Root graduated from New York University School of Law in 1867, a time of momentous change in the legal profession. The banks, trusts, and conglomerates operating in New York needed lawyers who could negotiate as well as litigate. Eager to make a name for himself, Root charged headfirst into the budding field of corporate law, signing John J. Donaldson, President of the Bank of North America, as his first major client. Root’s work on behalf of Donaldson and the bank cemented his reputation as an attorney capable of serving the city’s commercial elite.

In 1873, Root joined the defense team of Boss Tweed, Tammany Hall kingmaker and New York City’s leading Democrat, who was on trial for embezzling public funds. The media frenzy surrounding the trial raised Root’s public profile, but his association with Tweed, whom the jury found guilty, tarnished his professional reputation. Ever mindful of his public image, Root distanced himself from Tweed and began aligning himself with the Republican Party instead.

In 1881, when an assassin’s bullet took out President James Garfield, a Republican, Root was in the right place at the right time: Chester A. Arthur, the sitting vice president, was Root’s close friend and client. Two years after Arthur ascended to the presidency, he appointed his buddy the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York. As a federal prosecutor, Root successfully defended the government’s anti-immigrant tax on foreign steamship passengers, and earned major Wall Street cred for his successful prosecution of James C. Fish, a prominent banker whose actions precipitated the Panic of 1884.

Root’s time at SDNY greatly enhanced his standing within the Republican Party, but in 1885, he returned to private practice. As detailed in Mike Wallace’s Greater Gotham: A History of New York City From 1898 to 1919, Root fell in with the city’s elite commercial class and joined them in solving that most vexing of problems: competition. Gilded Age elites believed in free-market capitalism right up until it became a nuisance. They assessed that by cooperating rather than competing—either by merging their corporations or bundling them into trusts—they could dominate workers, streamline supply chains, and make more money with fewer headaches.

Root with President Calvin Coolidge (center) and Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (walrus) (Photo by: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Root quickly established himself as an expert in organizing and protecting corporate entities. According to historian L. Michael Allsep, Root’s most important work “took place outside the public gaze and consisted of good advice rendered that kept his clients out of court and off the pages of the newspapers.” His firm, Root, Howard, Winthrop & Stimson, boasted a client list stocked with some of the most illustrious and notorious Gilded Age businesses, including John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, the Havemeyer Sugar Trust, the Lead Trust, and the Whiskey Trust. The journalist William Randolph Hearst lambasted Root as a protector of the corrupt, a “jackal” to Wall Street’s “hyenas.” But Root flourished because he understood power. He knew its sources, the means to channel it, and how to wield it on behalf of America’s commercial elites. In boardrooms, courtrooms, and clubhouses, Root and his clients bent the economy to their will.

They also wanted more. In 1898, the United States declared war on Spain. American forces easily defeated the Spanish in Puerto Rico, Cuba, Guam, and the Philippines, and the United States claimed the islands for its exclusive economic enjoyment. President William McKinley needed a new Secretary of War to manage the colonies, and he wanted Root for the job.

Tapping a civilian corporate lawyer as the nation’s top military official earned its share of skeptics. “No appointment seemed to me more ridiculous,” said Nicholas Murray Butler, Root’s friend and President of Columbia University. “I could not imagine Root as knowing anything about war or of military organization.” Root himself had his doubts. He had no real military experience, having spent the Civil War prancing around with a student militia company and playing baseball.

Still, McKinley insisted, because corporate experience, not battlefield experience, was what he was after. “I don’t need anyone who knows anything about war or the army,” said McKinley. “I need a lawyer to administer these Spanish islands we’ve captured, and you are the lawyer I want.”

Root with President William Howard Taft and Andrew Carnegie, c. 1909 (Photo by Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

The results were devastating. Root struggled to shore up the Philippines’ colonial government—led by future president and Supreme Court chief justice William Howard Taft—and his efforts to professionalize the army’s officer corps did nothing to stop American forces from committing horrific atrocities, such as the infamous “water cure.” American soldiers would force Filipino prisoners to drink water until their bellies swelled, then expel the water by beating the prisoners’ stomachs with the butts of their rifles.

Philip C. Jessup, Root’s close friend and biographer, stressed that Root never explicitly commanded American forces to kill civilians, and ordered an end to the “water cure.” But according to the anti-imperialist lawyer Julian Codman, a contemporary of Root’s, the Secretary of War deliberately misled the public about the scale and nature of American atrocities, never meaningfully enforced his anti-torture orders, and tacitly approved of his forces’ ruthless conduct.

The historical record supports Codman’s claims. Root, though well aware of American atrocities, asserted that his forces conducted their operations in the Philippines “with scrupulous regard for the rules of civilized warfare, with careful and genuine consideration for the prisoner and the non-combatant, with self-restraint, and with humanity never surpassed, if ever equalled, in any conflict.” The former United States Attorney also displayed remarkably little interest in prosecuting war criminals within his ranks. He forced Jacob Smith into retirement, but went no further. Waller was court-martialed, but acquitted by the military’s old boys club. Brigadier General J. Franklin Bell, the province commander infamous for forcing Filipino civilians into disease-ridden concentration camps, never received so much as a reprimand, despite the thousands of deaths attributed to his policies.

Ever the apologist, Root contended publicly and privately that most of his forces’ actions were reasonable or even necessary, and engaged in some astoundingly racist victim-blaming. In a letter to Senator John T. Morgan, Root described Filipinos as “little advanced from pure savagery… [having] many of the characteristics of children; the lack of reflection, disregard of consequences, fearlessness of death, thoughtless cruelty, and unquestioning dependence upon a superior.”

President Theodore Roosevelt sits with his Cabinet, including Secretary of State Elihu Root (Photo by George Prince/Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

Root didn’t limit his attention (and selective inattention) to the Philippines. Although Cuba was not formally a U.S. colony, Root fought vigorously to defend American interests in the young island nation. The Platt Amendment—authored by Root, adopted by Congress, and forced into the Cuban constitution despite considerable resistance—made Cuba an American protectorate, allowed American investors to dominate the nation’s sugar industry, and permitted the U.S. Navy to establish a base at Guantánamo Bay. It also provided grounds for American military intervention in Cuban affairs, which the United States exercised in 1906 and 1912.

Puerto Rico fared little better. The Foraker Act—passed by Congress on Root’s recommendation—secured the island’s colonial status and paved the way for American corporations to exploit the island’s resources and residents. The Supreme Court’s infamous Insular Cases, under which Puerto Ricans remain second-class citizens with limited constitutional rights, affirmed the legal regime Root established.

Although hundreds of thousands of civilians may have died on Root’s watch, the four years he spent governing the colonies greatly enriched American investors. To those who mattered, money mattered most, and when Root returned to private practice in 1904, the legal and commercial communities welcomed him back with open arms. The New York City Bar Association elected Root its president, and he quickly reclaimed his place as the city’s top corporate attorney.

In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt nominated Root Secretary of State, a position he held for four years. Ever mindful of his friends in New York City, Root used his new role to streamline avenues of trade and investment. Root negotiated arbitration treaties with 24 nations, for which he eventually received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1912—a stupendously absurd honor considering his record as Secretary of War just a decade earlier. Later, he served as president of the American Bar Association, and briefly in the U.S. Senate, where he continued to oppose Philippine independence.

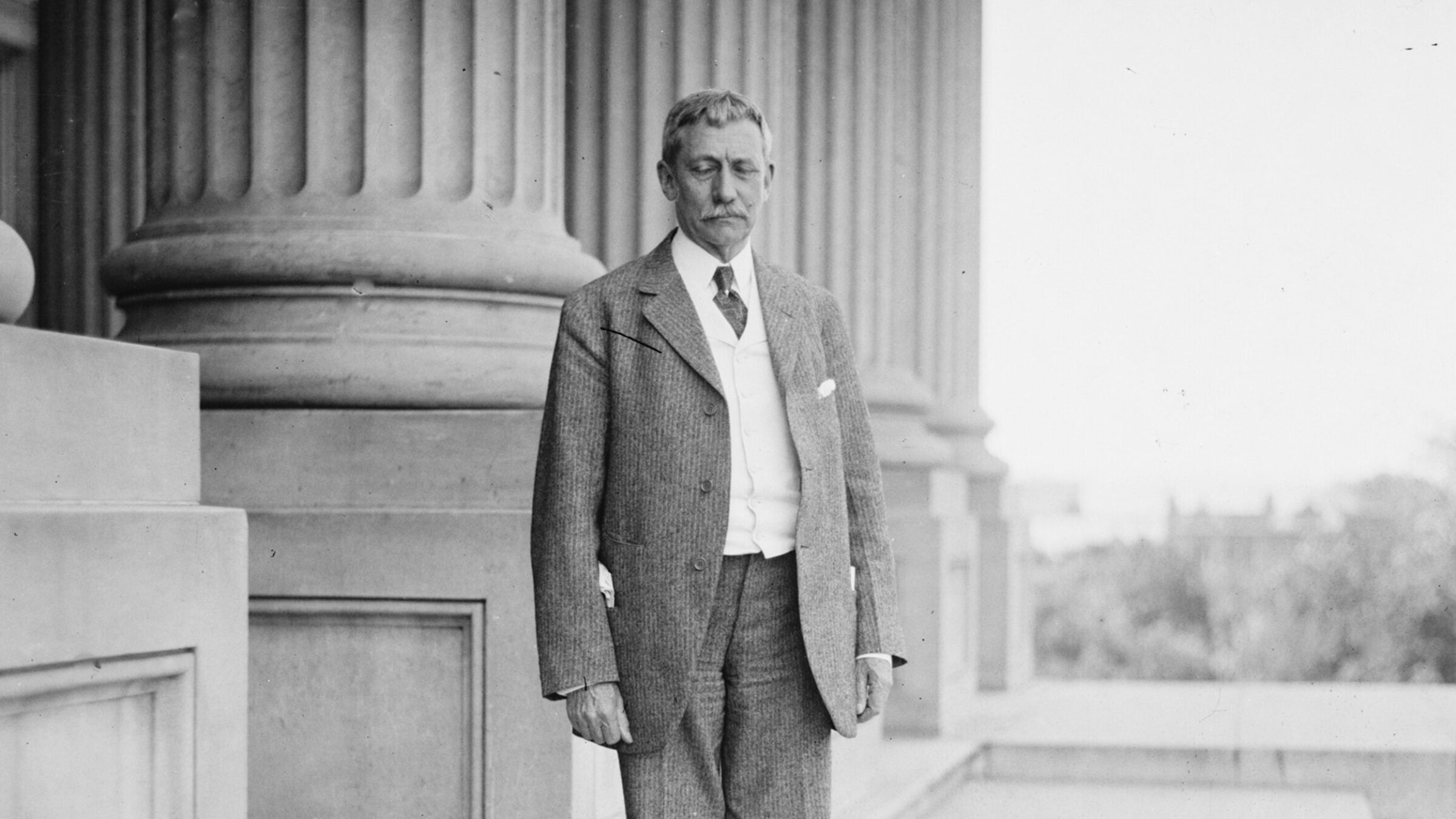

(Photo by Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

Though Root died over nine decades ago, his legacy is thriving. Root, Howard, Winthrop & Stimson, now known as Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman, remains a major law firm with some 700 attorneys and over half a billion dollars in annual revenue. The New York State Bar Association presents an annual Root/Stimson Award to lawyers who demonstrate “outstanding commitment to community and volunteer service and to the improvement of the justice system.” New York University Law School rewards top public interest students with Root-Tilden-Kern Scholarships. The school affectionately refers to recipients as “Roots.”

Meanwhile, Puerto Rico and Guam remain United States territories, and Congress continues to deny their people equal rights as American citizens. Although the Philippines eventually won its independence, the United States still maintains a large and growing military presence in the country. Cuban-American relations, marred by over a century of exploitation and abuse, remain an absolute catastrophe. One power-hungry, profit-driven corporate lawyer made it possible.

Purging Root’s name from awards and scholarships would be a welcome first step towards confronting the long-obscured evil of his work. Actually dismantling the lasting effects of that work is a different and far greater challenge. As long as attorneys, politicians, and the commercial elite chase power and profit without regard for human rights or racial justice, Root’s legacy will endure.