Last month’s Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice-to-be Ketanji Brown Jackson featured no shortage of histrionics (Lindsey Graham), inanities (Ted Cruz), and bluster (Tom Cotton). One important aspect of her career quickly became the target of disingenuous criticism from both inside and outside the hearing room: her time as a federal public defender.

Jackson had represented a range of clients while at the public defender’s office, including detainees held at Guantanamo who were designated as enemy combatants. Despite the long tradition of American lawyers defending unpopular clients against the government, Republican senators claimed her work could have allowed her clients to leave military detention and engage in terrorism. Lawmakers like Marsha Blackburn claim to love the Constitution — except, apparently, for the Sixth Amendment’s guaranteed right to counsel.

These criticisms rightly received pushback from across the political spectrum. But they also demonstrate how completely confused an eternal debate within the legal profession has become: Is it permissible to criticize lawyers for choosing to represent unpopular clients?

The short answer is almost always yes. For the most part, criticizing lawyers is just a form of counterspeech. And counterspeech, as a core component of the U.S. free speech tradition, is something that politicians and lawyers usually champion—except, of course, when it comes to criticism of themselves.

“…and then it says, ‘to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense!'” (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

The American Bar Association’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct state that “a lawyer’s representation of a client, including representation by appointment, does not constitute an endorsement of the client’s political, economic, social or moral views or activities.” But criticizing lawyers’ choice of clients doesn’t assume that the lawyer agrees with what their client says or does. Most lawyers make choices about who to represent, how, and why. And criticism that targets those lawyer’s choices, rather than a client’s characteristics, generally falls in bounds.

Opponents of lawyer criticism often cite John Adams’ defense of British soldiers accused of murder after the Boston Massacre. The choice to represent the soldiers earned Adams significant contemporary criticism, although later generations applauded it. Today, there is no shortage of similar controversies: lawyers defending Harvey Weinstein from sexual assault charges, or facilitating Theranos’s pursuit of journalists, or defending Nestle from allegations of condoning child slavery in the Supreme Court, or bolstering Donald Trump’s election lies. What’s the distinction between these debates and Jackson’s advocacy for indigent criminal defendants and Guantanamo detainees?

As with most things in the world, power and resources serve as the fulcrum. Criminal defendants and targets of national security charges face the power of the state at its apex, with long sentences and harsh punishments. These are politically unpopular constituencies, and these individuals have little reason to hope that the democratic process or the public writ large will care about their fates. As a result, the lawyers who represent those clients—from John Adams to Ketanji Brown Jackson—can get painted as soft on crime or sympathetic to “the enemy.”

This is wrong. Lawyers who represent them further the constitutional guarantees that protect the rights we all enjoy. Jackson herself made this point during the hearings. “That is what you do as a federal public defender,” she explained. “You are standing up for the constitutional value of representation.”

Taking power as our frame, the suitability of criticism increases when lawyers choose to represent clients who can employ any number of attorneys. Former Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal, a high-profile liberal attorney, received scathing critique for arguing at the Supreme Court that his clients, megacorporations Nestle and Cargill, should escape liability for allegedly aiding and abetting child slavery practices in Ivory Coast. The spectacle of a well-known Obama administration veteran claiming that, while child slavery might be beyond the pale under international law there was no norm against “aiding and abetting” it, was rightfully the subject of scorn.

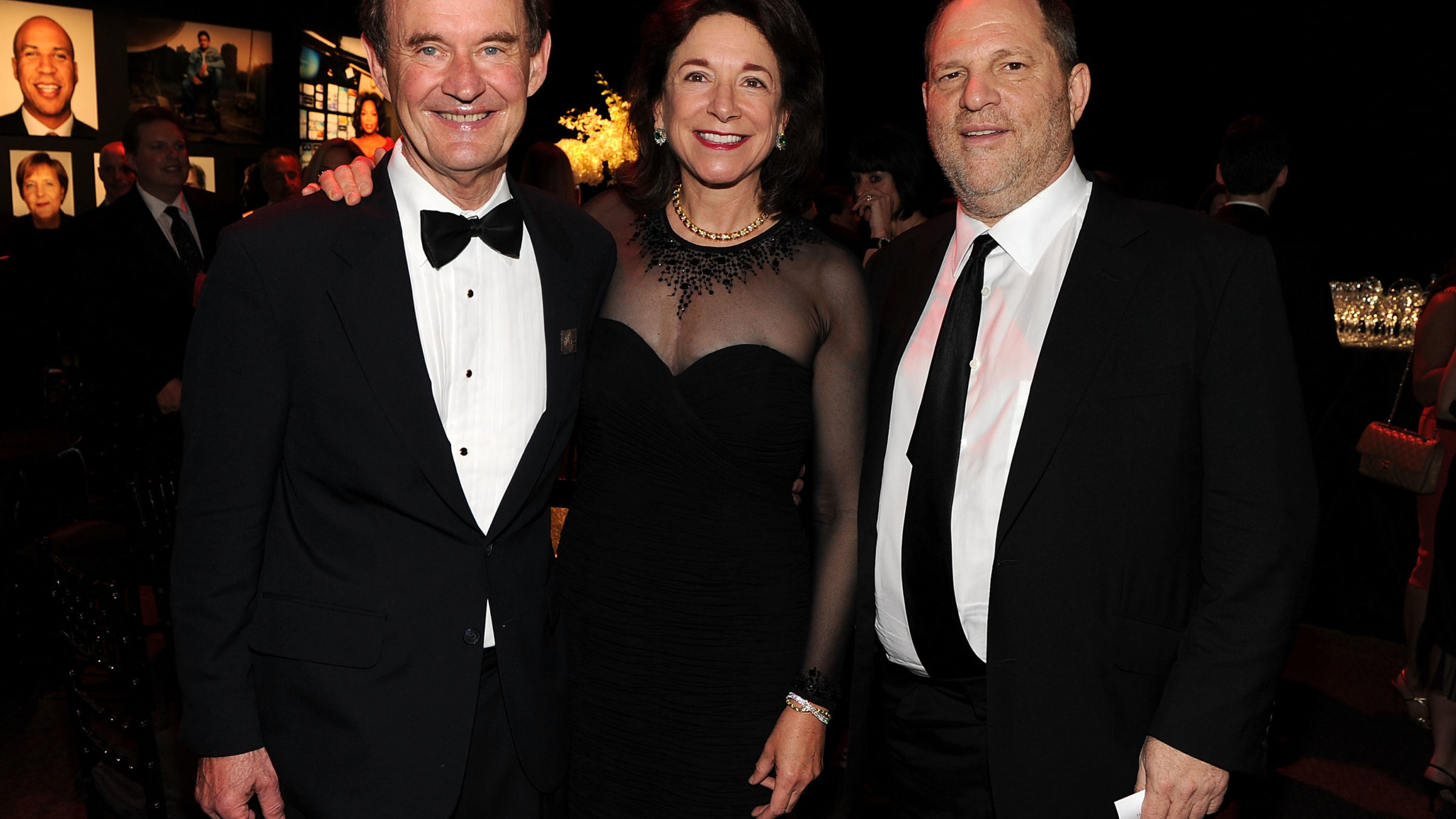

David and Mary Boies and Harvey Weinstein at the 2011 TIME 100 Gala in New York City (Larry Busacca/Getty Images for Time Warner)

The clubby Supreme Court bar, unsurprisingly, closed ranks. Tom Goldstein, the founder of SCOTUSblog and a frequent Supreme Court advocate, argued that the political left was “eating its own,” and that Katyal “just happens to work for a corporate law firm, with its corporate clients.” It’s telling that such an experienced lawyer couldn’t come up with better defenses. Saying that criticism amounts to self-sabotage inappropriately insulates high-profile figures from pushback—a “trust your betters” mentality that the left should eschew. And corporate law firms with experienced attorneys don’t just “happen” to represent certain clients or make certain arguments. They are not public defenders appointed to take on those who can’t afford representation. Law firms choose deliberately who to take on and who to pass on; there’s nothing accidental about it.

The same principle applies elsewhere. Harvey Weinstein had so much power, money, and influence that he could retain attorneys like David Boies to insulate himself from liability and consequences for decades. When Boies represented Weinstein, he was cashing a check, not working for a client to further a constitutional principle. Cleta Mitchell wasn’t the only lawyer available to try to pressure Georgia’s Secretary of State to certify Trump as the winner of that state in the 2020 election. The literal President of the United States was hardly a disempowered actor in an unequal system run by the state, and his lawyers weren’t taking on a special burden that their critics need to keep in mind.

Treating lawyer criticism as counterspeech emphasizes how subjective it is. My belief that David Boies should be shamed for choosing to represent Harvey Weinstein and cover up his misdeeds isn’t objectively true. Such criticism, like counterspeech generally, is in the eye of the beholder. The debate ultimately amounts to a disagreement about whether lawyers deserve immunity from criticism. They don’t. The cancel culture brigade wrongly argues that having to face consequences for your ideas, or your choice of clients, is unfair and unwarranted. Having a law degree doesn’t make your professional choices unimpeachable. Criticism also doesn’t cancel your law license, as Katyal, Boies, and Mitchell, none of whom have been disbarred, can all attest.

Lawyers who get called out for choosing clients who perpetuate inequality or peddle antidemocratic lies shouldn’t be insulated from the criticism merely because they are lawyers. Lawyers aren’t special. We’re not inherently more neutral, or fair, or learned than anyone else just because we swear an oath at the bar admission ceremony. Those who insist otherwise are really just objecting to being held accountable.