Last week, Justice Stephen Breyer issued a solo statement criticizing the Court’s decision to deny the certiorari petition of Joe Clarence Smith, a man who has been awaiting execution on death row for over 44 years. The justices couldn’t be bothered to weigh in on whether the four decades Smith has languished in a cell measuring 84 square feet constitutes “cruel and unusual” punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment.

In his statement, Breyer expressed concerns about “the excessive length of time” that Smith and others on death row have spent awaiting an uncertain fate. That time, he said, “raises serious doubts about the constitutionality of the death penalty as it is currently administered.”

This is hardly the first time a Supreme Court justice has questioned the constitutionality of the death penalty. In 1972, the Court in Furman v. Georgia ruled the death penalty unconstitutional in Georgia and Texas. All five justices in the majority wrote separate concurrences to explain their reasoning; Justice William O. Douglas focused on the racial disparities in capital punishment, and explained that the wide discretion afforded to judges and juries allowed racism and classism to permeate the process sentencing. “Discrimination is an ingredient not compatible with the idea of equal protection of the laws that is implicit in the ban on “cruel and unusual” punishments,” Douglas wrote.

Justices William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall would have gone even further. Both men stated that they thought the death penalty always violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment, regardless of how carefully state legislature drafted its sentencing guidelines. “There is no rational basis for concluding that capital punishment is not excessive,” Marshall wrote.

For four years, while state legislators in Texas, Georgia, and elsewhere worked tirelessly to rewrite statutes to satisfy the Court, no state killed anyone. Then, in Gregg v. Georgia, the justices upheld the death sentences of five men and affirmed the constitutionality of capital punishment. The concerns in Furman about arbitrary administration, wrote Justice Byron White, could be satisfied by “a carefully drafted statute that ensures that the sentencing authority is given adequate information and guidance.” Joe Clarence Smith, whose appeal the Court denied last week, was sentenced to death one year later.

Since then, foundational objections to the death penalty have been rare. In one of his last dissents before retiring in 1994, Justice Harry Blackmun declared the Court’s post-Furman era a failure and shed all reservations about publicly critiquing the death penalty. After 20 years, Blackmun had enough. “From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death,” he wrote in Callins v. Collins, six months before his retirement.

Breyer, who replaced Blackmun that fall, had his Callins moment two decades later, in a 40-page dissent in Glossip v. Gross in 2015. Although the question in that case was about Oklahoma’s lethal injection method, Breyer called for briefing on the constitutionality of the death penalty itself, which, he said, involves “fundamental constitutional defects.”

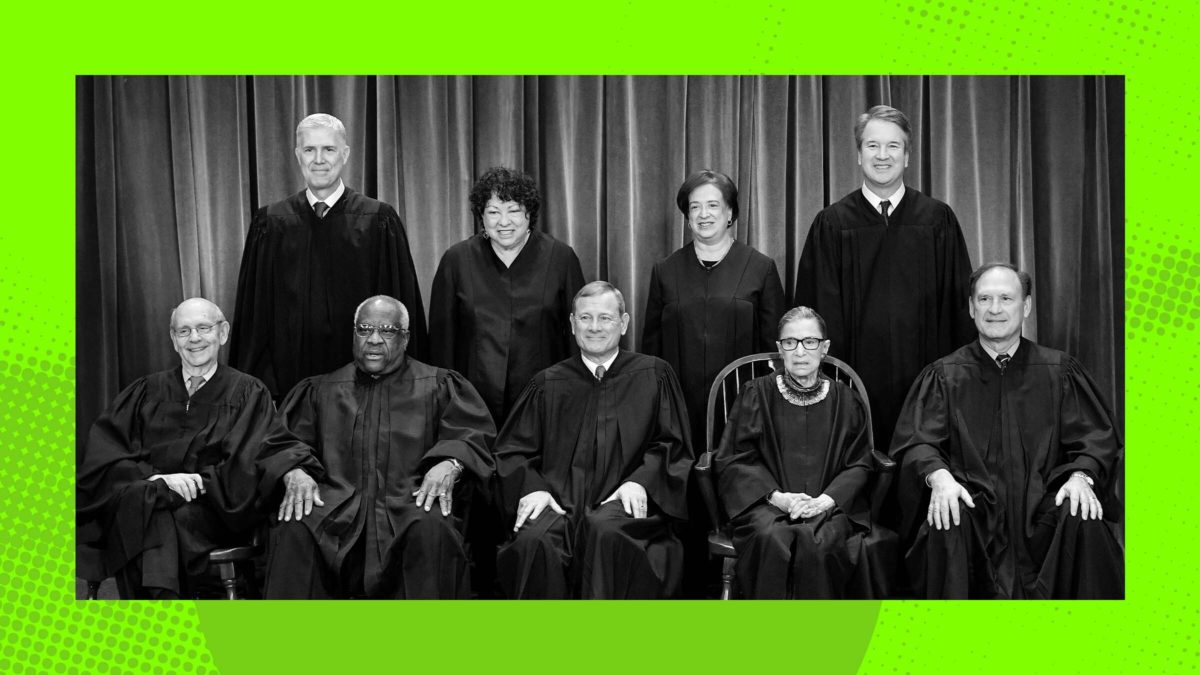

Since then, he has routinely dissented in cert denials that allowed for executions which he thought violated the Constitution. In 2018, he reiterated his belief that “unconscionably long delays” make death sentences unconstitutional. A year later, Breyer suggested that there may be “no constitutional way to implement the death penalty.” In 2020, when the federal government re-started executions for the first time in nearly two decades, Breyer, joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, dissented in light of the death penalty’s “serious legal defects.”

This most recent cert denial in Smith’s case is actually the third time Breyer has objected to Smith’s sentence. In 2007, Smith argued that his death sentence’s delayed nature made it unconstitutional. The justices denied his request with only a dissent from Breyer. Ten years later, after the Court denied another cert petition from Smith, a mournful-sounding Breyer asked, “What legitimate purpose does it serve to hold any human being in solitary confinement for 40 years awaiting execution?”

Only Ginsburg, who died in 2020, joined Breyer in Glossip. And while Justice Sonia Sotomayor frequently dissents from denials of cert in death penalty cases, she generally limits her critiques to the process, not the validity of the punishment itself.

That Breyer is soon leaving the Court reflects how far the Court has shifted since Furman, when the justices were seriously considering whether capital punishment could ever be constitutional. Today’s Court, by contrast, only tinkers around the edges. It concerns itself with how painful an execution can be, or whether a priest may lay hands on a man about to be executed, or whether a state can force someone to choose their method of execution, or execute someone after withholding evidence of their innocence. In most death penalty cases that come before it, the Court will simply greenlight executions without comment. Now, the best that people facing the death penalty can hope for is that the nation’s highest court will at least allow them to pray first.

Correction: A previous version of this post misstated the year of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death. It has been updated.