As the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority prepares to end constitutional protections for abortion after five decades of trying, the Washington Post’s editorial board has identified the next great crisis for democracy: people raising their voices a little too loudly in Washington’s upscale residential neighborhoods.

Since the publication of a draft opinion that would overturn the landmark Roe v. Wade decision, a few dozen people have gathered for peaceful protests at the suburban homes of Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and Justice Sam Alito. On Monday, the board condemned these demonstrations as “disturbing,” “problematic,” and “noisy.” As we all know, no justice should ever have to suffer the indignity of turning up the TV volume to hear Mayim Bialak read the clue on Final Jeopardy.

The crux of the editorial’s argument is that protests impermissibly taint the legal process, which, the board explains, “must be controlled, evidence-based and rational if there is to be any hope of an independent judiciary.” This assumes that the process by which the Court would suddenly dispose of Roe, a 50-year-old decision that protects a basic right to bodily autonomy—one around which millions of people over multiple generations have organized their lives—is “controlled, evidence-based and rational” in the first place.

It is not. From the moment the decision was announced in 1973, conservative legal academics have waged a relentless PR campaign to cast its reasoning as specious and weak. Conservative elites set up organizations like the Federalist Society as pipelines for prospective judicial candidates, carefully vetting young lawyers to gauge their fealty to anti-choice politics. Right-wing donors have spent untold sums of money to elect Republican politicians, who in turn have stacked the federal judiciary with the upper echelon of ideologues eager to follow through on this promise.

The phrase “independent judiciary” raises the obvious question of from what, exactly, the judiciary is supposed to be independent. But to the extent it ever means anything, the anti-choice movement extinguished any “hope” of an independent judiciary a long time ago. The conservative war on Roe is a careful, calculated effort to enshrine a preferred policy outcome into law using the trappings of legal process. It is embarrassing for the Post to treat this outcome as the inexorable product of an “evidence-based and rational” system simply because the people in power have “Justice” before their names.

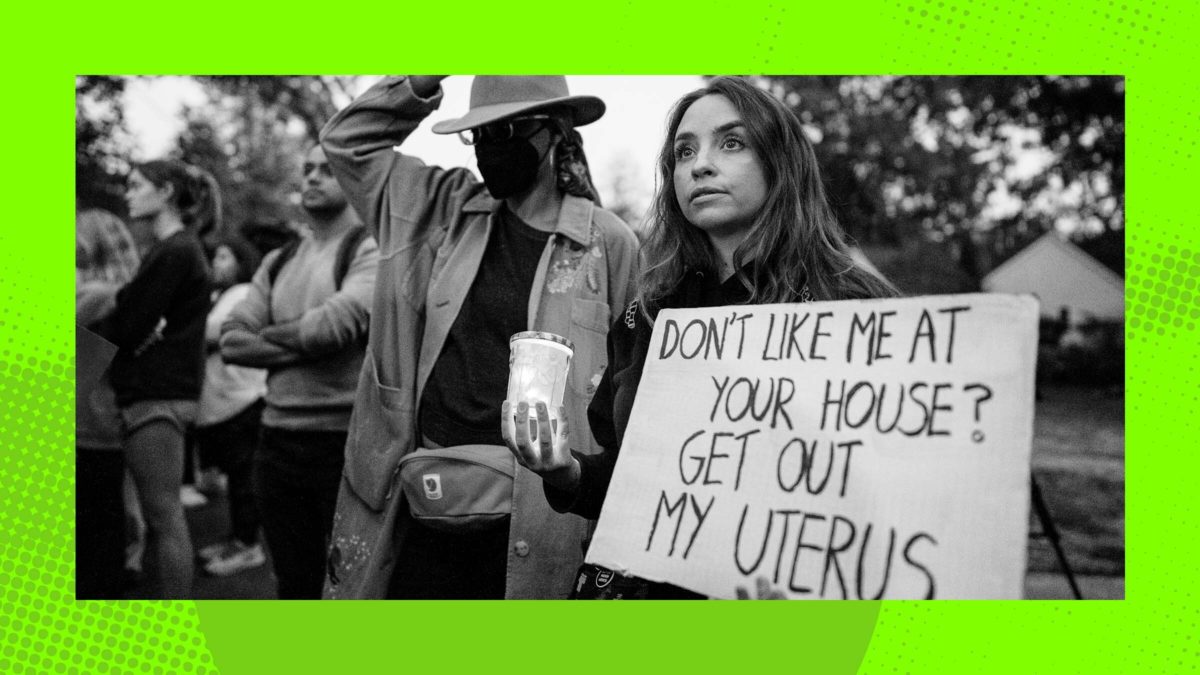

Protesters gather near the Virginia home of Justice Samuel Alito on May 9 (Photo by STEFANI REYNOLDS/AFP via Getty Images)

The board goes on to acknowledge that Roe’s defenders believe overturning it would “violate core judicial principles.” Just as quickly, however, it brushes aside the prospect of confronting the Court’s towering failures as less important than maintaining the Court’s sagging reputation. “If basic social consensus and the rule of law are to be sustained—and if protesters wish to maximize their own persuasiveness—demonstrations against even what many might regard as illegitimate rulings must respect the rights of others,” the board writes.

Set aside, for a moment, the notion that Alito and his colleagues—people who have spent their entire careers steeped in a movement to end Roe—are “persuadable” on this issue. When it comes to maintaining a “basic social consensus,” the bloodless rollback of decades of civil rights progress and a few hours of indignant chanting in public places are not equally dangerous threats.

This sniffing apologia ignores what feels like an obvious truth: Respect for the “rule of law” must be earned by the people with the power to shape it. An illegitimate ruling from an illegitimate body does not deserve to be treated as anything else.

The editorial closes by going full Hall Monitor, invoking a Montgomery County ordinance that bars protests in the form of “stationary gatherings,” and a federal law that prohibits “pickets or parades” at judges’ residences. “These are limited and justifiable restraints on where and how people exercise the right to assembly,” the board opines, urging the authorities to take “appropriate action” against anyone with the temerity to disobey.

This reasoning upholds an insidious double standard: In 1994, the Supreme Court struck down as overbroad an injunction that instituted a 300-foot protest “buffer zone” around the homes of Florida abortion clinic workers. The opinion specifically called out the injunction for purporting to restrict “marching through residential neighborhoods” or “walking a route in front of an entire block of houses,” both of which sound like apt descriptions of the First Amendment activity occurring on Sam Alito’s street as of late. Picketing over abortion rights is not new. The only difference now is that it is affecting powerful people who are not used to being on the receiving end of it.

The Court has even been more solicitous of protesters at abortion clinics, tacitly blessing the rampant intimidation of people seeking to exercise their rights with the imprimatur of free-speech legitimacy. For decades, anti-choice picketers have harassed doctors, nurses, and staffers, shouting them down in public, publishing their names and addresses, and occasionally shooting them to death during Sunday morning church services. Nationally, providers endure dozens of assaults, hundreds of death threats, and thousands of pieces of hate mail every year. An anti-choice movement emboldened by the fall of Roe is only going to get angrier, scarier, and more violent.

To a federal judge, the specter of family dinners interrupted by “Our body, our rights” chants outside might feel like an emergency. (In a revealing glance at where the Senate’s priorities lie, an upper chamber that regularly squabbles over the particulars of freeway repair funding managed to unanimously pass a bill to provide extra security for Supreme Court justices and their families.) But for clinic workers—people who have to go to work with the conservative movement’s targets slapped on their backs—protests are part of everyday life. If a handful of mean signs is the worst thing they encounter in a given week, they consider themselves fortunate.

(Photo by STEFANI REYNOLDS/AFP via Getty Images)

Also absent from the board’s argument is any acknowledgement that the Supreme Court building has been transformed into a miniature fortress, surrounded by hastily-erected fences that render meaningful protest more or less impossible. Federal law has long prohibited demonstrations on the building’s marble plaza, confining protesters to marching a narrow sidewalk where your average septuagenarian justice would have trouble reading their signs from the courthouse’s front steps. There is no better illustration of the Court’s insulation from the real-world consequences of its work than physical barriers that protect members from encountering anyone for whom the law is more than a philosophical debate.

Perhaps the most perplexing aspect of the Post board’s stance is its substantive one: It broadly agrees with protesters who assert, as it wrote on May 3, that overturning Roe would be a “grievous blow to freedom in the United States—and to the legitimacy of the court itself.”

To anyone who does not fetishize the federal judiciary as operating scrupulously above the political fray, these positions are not reconcilable. In this warped hierarchy of injustices, voicing objections to an unconscionable incursion on personal liberty is not worth the price of making life-tenured judges feel briefly, mildly uncomfortable. It is one thing for the American legal system, as it always does, to demand civility and graciousness in the face of cruelty and misogyny. It is another for Rule of Law enthusiasts wrapped in institutional privilege to tout this bargain as fair and reasonable for everyone involved.

Scolding people for peacefully meeting Supreme Court justices where they live is to insist that Supreme Court justices, simply by virtue of being Supreme Court justices, are above criticism altogether. This is wrong. In a country that aspires to be a representative democracy, powerful people who abuse their power should be made to feel uncomfortable. If you purport to stand for a given outcome but discourage the one action normal people can take to promote it, you’re not standing for anything.