The Resume

Compared to some other federal judges, Chad Readler is a man of the people. Chad didn’t go to an elite, Ivy League law school, and he didn’t get clerk for some high-falutin Supreme Court Justice. He made his own way in the world after graduating from Michigan, one of the nation’s elite law schools outside of the Ivies, and clerking for Reagan appointee Alan Norris on the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, one step below the Supreme Court.

After his clerkship, he worked at Biglaw firm Jones Day for 20 years. Jones Day’s lawyers are some of the most conservative of all large law firms. It’s long been a corporate litigation powerhouse, regularly representing corporate employers in disputes with their employees and fighting countless federal rules that could hurt corporate profits. And it’s quietly resolved claims that it fostered a frat party atmosphere and underpaid women who worked there. Small wonder that its lawyers filled the ranks of the Trump Administration.

Chad fit right in at Jones Day, representing clients like R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company when it challenged bans on cigarette advertisements near schools and Wells Fargo when it foreclosed on people’s homes. He also represented Donald Trump’s campaign in Ohio and Pennsylvania in 2016, back when Trump’s electoral strategy involved fewer coup attempts. In one case, after Trump suggested at an Ohio rally that his voters should monitor “certain areas” and patrol polling places to intimidate minority voters, the Ohio Democratic Party sued the Trump campaign seeking an injunction to stop the Trump campaign from doing so. And they won – until Chad helped Trump skate by on appeal. All his hard work must have made an impression on Trump, because he was in the first wave of Jones Day lawyers that swept into the Justice Department in January 2017.

At the Justice Department, Chad was the Assistant Attorney General appointed to run the Civil Division, which is supposed to defend against challenges to federal agency policies. While there, he signed onto a brief arguing that the Census Bureau had completely legitimate reasons for asking everyone in America if they were a citizen. That case went to the Supreme Court, which narrowly held that the Census didn’t adequately explain its reasons for asking a citizenship question. In a completely unpredictable twist, Trump’s Commerce Secretary later admitted that he had added the question after virulent racists Steve Bannon and Kris Kobach asked him to. Bannon and Kobach hoped that the question would scare noncitizens and undocumented people from answering the Census. So all of Chad’s briefing had been a legal fig leaf for a failed xenophobic pressure campaign. A normal person might feel guilty after participating in a racist coverup like that. Chad got nominated to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Opinions

As a Sixth Circuit judge, Chad’s main priority appears to be protecting people in power from consequences. Usually those people are police and jail officials, but sometimes they’re huge, monied organizations. Let’s start with the cops. Although Chad isn’t an automatic vote to grant qualified immunity to cops, his record leans in one direction. Chad has upheld qualified immunity for police and jail officials when officers tore a woman’s ACL while arresting her and then neglected to give her medical treatment in jail. He’s upheld qualified immunity for jail officials and a nurse who failed to give an inmate her prescription antacids after she had gastric bypass surgery, causing her to develop ulcers so serious she needed surgery. And he’s upheld qualified immunity for jail guards who failed to stop a contracted doctor from sexually assaulting at least three different women.

Chad’s opinion in that last case is particularly baffling. In Buetenmiller v. Macomb County Jail, the women argued that the jail officials were deliberately indifferent to the risk that the contracted doctor could assault them while the doctor was examining them alone. The company that employed the doctor had a policy that its employees needed chaperones if they were performing “sensitive exams,” but the jail failed to supervise him. One of the inmates even alleged that an officer once peeked through the privacy curtain and gave the doctor “kind of like a head nod.” But, Chad held, this wasn’t enough. According to Chad, jail officials needed to be aware that this doctor, specifically, was assaulting inmates, rather than be aware that he was repeatedly violating a policy that was only in place to prevent assaults. Chad wrote that by claiming the jail officials should have intervened and sent in a chaperone, the inmates were really asking jail officials to risk “interfering with the practice of medicine, something [county sheriffs are] not authorized to do.” Most people would not characterize the doctor’s conduct as “the practice of medicine,” but then again, most people are not on the Sixth Circuit.

Chad’s protection extends to prosecutors, too. In Price v. Montgomery County, police got a confession from a witness who claimed she had helped Nickie Miller murder a man in cold blood. The only problem was they knew the confession was unreliable. The witness had lied about key facts and kept changing her story every time she talked to them, and she immediately tried to recant her confession multiple times. She even wrote letters that expressly recanted her confession. Miller’s defense attorneys got a court order for the letters. But Miller never got them, because the prosecutor told the witness to destroy the letters. That’s what prompted Miller’s lawsuit.

Some courts allow defendants to sue prosecutors when they destroy evidence. But Chad held that the Sixth Circuit wouldn’t be one of those courts. Allowing judges to hold prosecutors accountable for destroying evidence that could exonerate a criminal defendant, Chad wrote, would “tie the hands of prosecutors by requiring them to maintain and preserve everything collected as evidence, regardless of relevance.” That reasoning doesn’t make any sense. If Miller had won, prosecutors in the Sixth Circuit would only have had to maintain evidence that exonerated the people they’re investigating, evidence they’re already required to turn over to criminal defendants under a Supreme Court case called Brady v. Maryland. But the state’s argument was good enough for Chad.

Finally, last year, Ohio State University tried to dismiss well-founded complaints that it knowingly allowed the school’s athletic program doctor to molest hundreds of student athletes for decades. The plaintiffs had filed suit after an investigation revealed that the university had known about the doctor’s misconduct for years and covered it up. Normally, plaintiffs have two years to file suit under Title IX. A panel of the Sixth Circuit allowed the case to proceed, holding that Title IX allowed them to file suit within two years of discovering that they had reason to sue the university rather than two years after the abuse occurred. Ohio State asked the full Sixth Circuit to hear the case, but a majority of the judges voted not to.

Chad dissented, angrily. He argued that Supreme Court precedent demanded the case be dismissed. (The Supreme Court apparently disagreed, as they denied Ohio State’s petition for review earlier this year.) Chad clarified that he found Ohio State’s conduct to be reprehensible, but from his review of the evidence, the doctor’s abuse was an “open secret” on campus and the plaintiffs should have intuited that the university could be liable. And he accused his colleagues of motivated reasoning, heavily implying that they had decided that Ohio State would be found liable and made up an opinion to support it. Weirdly, for this point, he cites Alice in Wonderland – as though the university was trapped in the realm of the mad Queen of Hearts instead of a disaster of its own making.

The Weird Shit

While still an associate at Jones Day, Chad (like your humble author) got in the business of crafting legal takes and submitting them for publication. And Chad (also like your humble author) wrote pieces criticizing judges. But the similarities end there.

In 2004, Chad wrote a preview of a then-upcoming Supreme Court case, Roper v. Simmons. The Missouri Supreme Court had decided that executing minors violates the Eighth Amendment, and the state of Missouri appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the Eighth Amendment did not bar executing 16- or 17-year-olds. Nearly twenty years later, that still sounds bad. Chad went a little further than Missouri, though.

The title of his article, “Make Death Penalty for Youth Available Widely,” tipped his hand somewhat. It began “If the United States is to have a death penalty, and 38 states and the federal government have said we should, then the penalty should be available in nearly all instances in which someone commits a capital offense, including when the offender is 16 or 17.” So, to be clear, rather than arguing that the Eighth Amendment did not specifically prohibit executing children, Chad was arguing that the government should categorically be able to execute them.

At the time, the Supreme Court had recently decided that the Eighth Amendment barred executing people who are mentally disabled in part because it found that there was an evolving national consensus against the practice. Law-and-order types worried that the Court would extend protections to children for the same reason. To try to head this off, Chad argued that actually, Americans loved killing kids. They just didn’t know it yet. “[W]hile opinion polls suggest that most Americans may oppose the use of capital punishment for juvenile offenders,” he wrote, “many may take a different view when they consider the facts of a specific case.” His evidence was the fact that the jury had sentenced the defendant in Roper to death. See? These twelve Missourians wanted to kill this kid! Therefore, everyone would want to kill this kid!

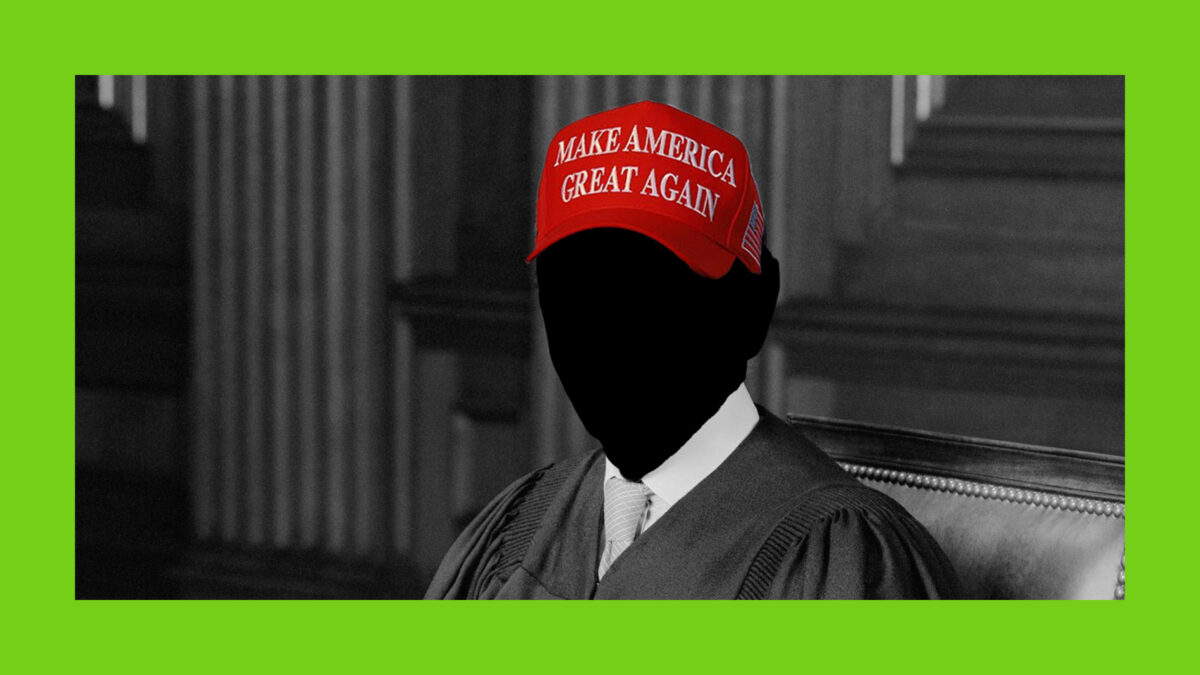

Thankfully, Missouri’s arguments didn’t prevail in front of the Court. But Chad’s article is a perfect example of the mindset of the prototypical Trump judge: stupid, cruel for the sake of being cruel, instinctively against nebulous ideas like “decency” and “human rights.” On the Sixth Circuit, Chad’s been able to keep writing similarly cold, authoritarian diatribes, but now his word is the law. It’s a safe bet that he wants the chance to take his game to the next level.