If you ask a lawyer to describe what the phrase “thinking like a lawyer” means, there is a good chance the response you get will include a reference to the movie The Paper Chase. Since its release in 1973, its antagonist, the fictional Professor Charles Kingsfield, has become a favorite character of lawyers and law professors who suffer from severe cases of Stockholm Syndrome. Kingsfield’s fearsome classroom antics provide some great, self-serving justification for those who spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on a law degree: In one of the movie’s most famous scenes, the tight-lipped, bowtie-clad Kingsfield struts in front of his bright-eyed new law students like he is ready to share some important wisdom that only he can appreciate. “You come in here with a skull full of mush,” he says. “You leave thinking like a lawyer.”

Clip via YouTube

Every first-year law student has probably heard some version of this from a professor: that the most important thing they will do in law school is learn is to “think like a lawyer.” (According to this amazing wikiHow page, thinking like a lawyer requires one to strip a problem down to its key facts to identify relevant legal issues, and then to try to derive a logical solution by applying general legal rules to the specific facts.) Lawyers talk about themselves as uniquely “rational, logical, categorical, linear thinkers”—a debatable proposition, but still, you could fill a library with all of the books written (by lawyers, of course) about how useful it is for law students and non-lawyers alike to start thinking more like them.

This sounds kind of great if you don’t think about it too hard; there is nothing inherently wrong with trying to approach problems logically. The problem, however, is that Kingsfield’s “mush” that lawyers rid themselves of—and learn to deride in others— includes major factors that influence the outcomes of individual cases, as well as how the justice system functions as a whole. To “think like a lawyer” means setting aside empathy for people the law ignores; the context in which those laws exist; and any kind of analysis of who does and doesn’t have power in the legal system. Taken to its all-too-common extreme, this ability acts as a shield against accountability for the harms perpetrated by lawyers, to the benefit of those already in power.

In the legal field, it is considered perfectly acceptable—even laudable—for lawyers to pursue careers actively advancing harm, acting as hired guns for the highest bidders. Corporate lawyers like Neal Katyal can snag prestigious jobs in Democratic administrations and be lauded as liberal heroes all while grinding people under the heels of corporate America and incompetent governments. Defending multinational corporations against charges of child slavery, arguing that towns should be allowed to rob retirees of their homes over minor tax debts, and trying to force the parents of disabled children to pay for private school when public schools violate the Individuals with Disabilities Act—all of this is just zealous advocacy on behalf of a client. “Thinking like a lawyer” means not thinking too hard about the real-world consequences of your actions.

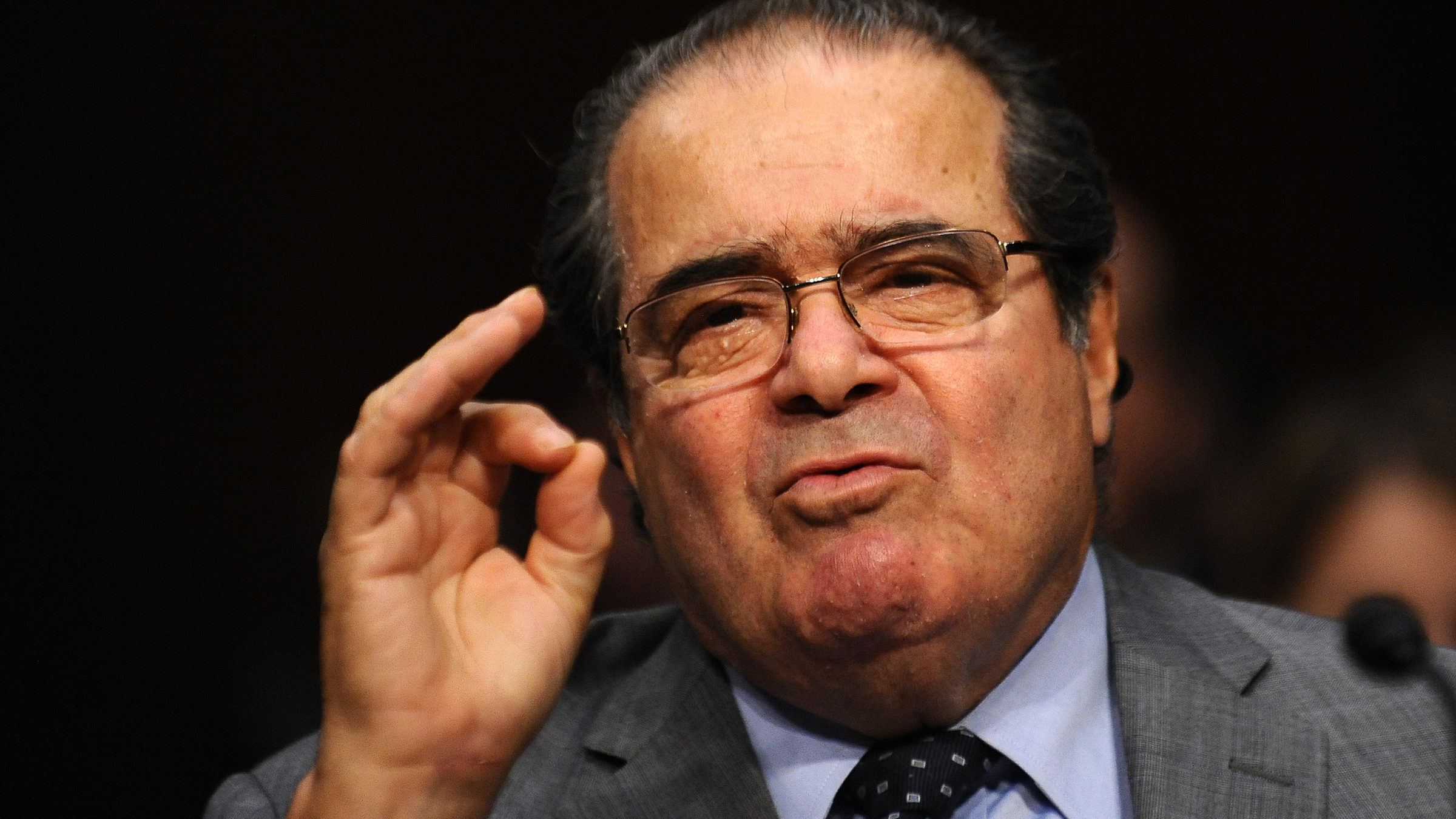

The mantra also means grading other lawyers—especially judges—on a generous curve. Plenty of self-professed liberal lawyers love to hate the racist, sexist Justice Antonin Scalia, professing disagreement with his opinions but begrudging admiration for his supposedly sharp legal philosophy. Although Scalia helped lay the groundwork for (among many other things) the end of bodily autonomy, the disappearance of affirmative action, and the ongoing right-wing push to drive LGBTQ people from public life, for many lawyers afflicted by the love of logic, none of Scalia’s obvious faults have pierced his veneer as an important legal intellectual.

Lastly, “thinking like a lawyer” means narrowing the scope of what you think about. Most lawyers learn legal history only in the form of cases, which not only obfuscates the real-world consequences of legal opinions, but also gives the impression that major wins for civil rights have come simply from clever legal arguments. Casebooks largely ignore factors outside the legal system that paved the way for these outcomes: Before Brown v. Board of Education, for example, Black veterans returning from World War II began organizing their communities, which helped spark the Civil Rights Movement. Before Roe v. Wade, the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique kicked off the second-wave feminist movement, which was pushing for gender equality long before courts showed up. And before Obergefell v. Hodges, activists had spent decades organizing for LGBTQ rights, from the Society for Human Rights to the Stonewall Uprising to the National March on Washington.

Lawyers didn’t make these changes happen with “logic.” They benefited from the work of organizers who made change possible in the first place. The “thinking like a lawyer” mindset erases this history, reducing it to, at best, a footnote in a Supreme Court opinion, if it gets mentioned at all. This artificial distinction between law and organizing is a serious weakness in legal thought: Lawyers are of course involved in efforts to reform the system, but for far too many of them, “thinking like a lawyer” stunts their imaginations about what change can look like. The idea that making a stirring speech in a stuffy courtroom will yield a big win is tantalizing; it is also nearly always wrong.

When someone spending the summer at Jones Day nails a cold call (JEWEL SAMAD/AFP via Getty Images)

Consider the Court’s recent decision to gut of race-conscious college admissions in Students For Fair Admissions v. Harvard. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson took apart Chief Justice John Roberts’s purportedly originalist majority opinion, showing that the Framers embraced race-conscious remedies to address racism. But as a dissent, her opinion has no force of law. There is no clever argument that will back Roberts into believing that racism still exists, or persuade Clarence Thomas that Americans shouldn’t be issued guns at birth, or convince Samuel Alito that Fox News may be lying to him. Legal arguments without a power-building strategy provides only false hope.

The problems inherent in “thinking like a lawyer” are not limited to the legal profession. This country’s unusually powerful Supreme Court gives legal thinking an outsized influence over the government, which lawyers dominate even outside of the judiciary. One empirical study found that over a two-century period, lawyers averaged 62 percent of seats in the House and 71 percent in the Senate. Another found that elite law students are “less fair-minded” and prioritize efficiency over equality in government. Still another survey found that where there are lawyers in the halls of power, they tend to back policies that wealthy people like.

Thinking like a lawyer can work incredibly well for those interested in maintaining the status quo. But even among those who are not, this constrained manner of thinking inhibits one’s ability to challenge existing power structures: Far too many liberals are content to work within this system, trying to think of killer arguments to trick Sam Alito into ruling for civil rights or insisting that an ethics code will change the Court’s conservative dominance. It is worse than a waste of time; it steals attention and resources from the grassroots movements that actually have a chance of making change happen.

Lawyers on the left need to see “thinking like a lawyer” for what it is: a sometimes-useful tool in a courtroom, and nothing more. Until then, they will always be swooping in to claim credit for the hard work of others, playing a game with rules written by and for those already in power.