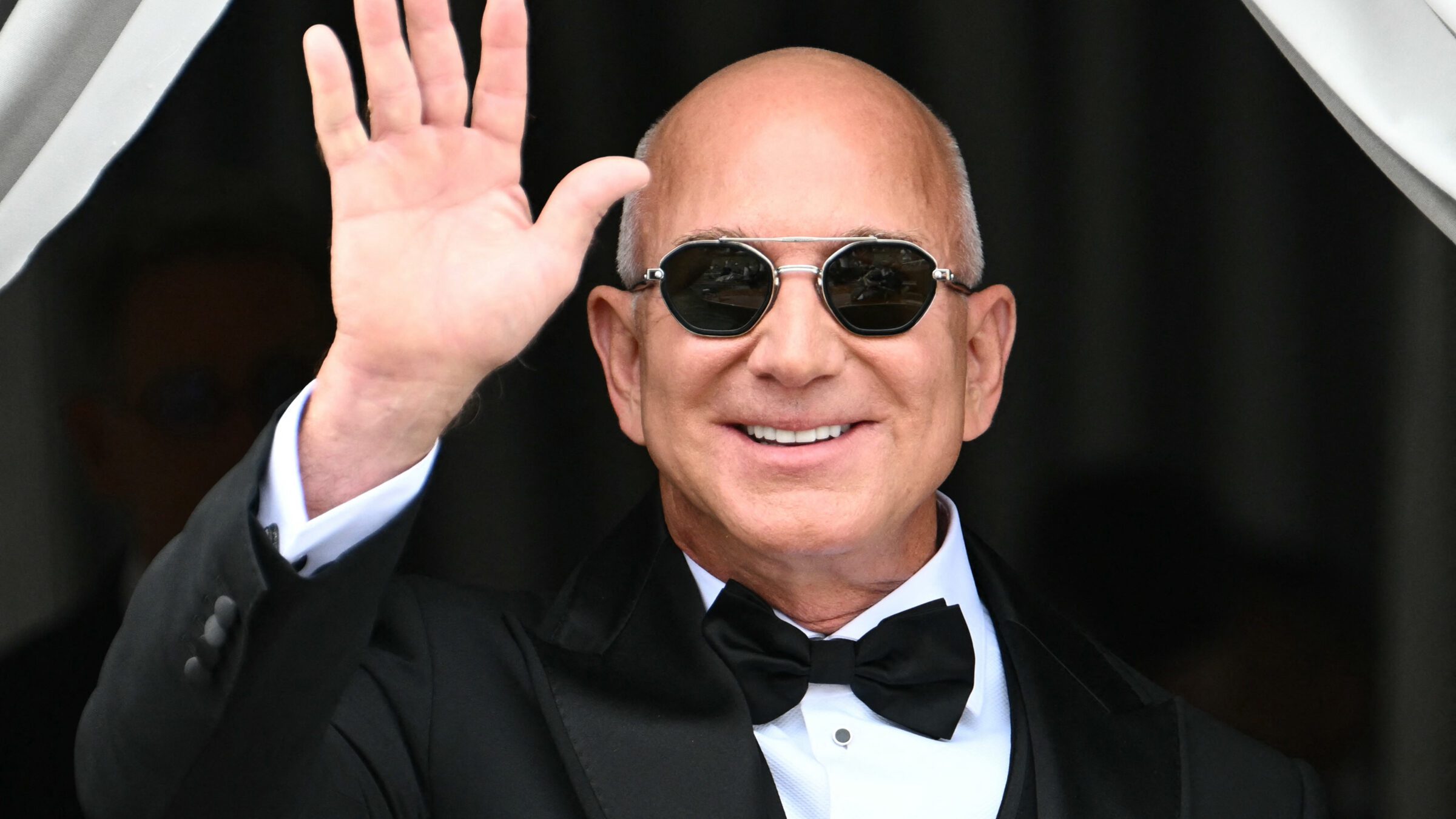

Earlier this year, Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos announced a new direction for the paper’s opinion section, which, he said, would write “every day in support and defense” of two “pillars” of American success: personal liberties and free markets. Many Post staffers, unsettled by a billionaire’s implementation of a mandatory quota for libertarian talking points, departed in short order.

In the months since, the board has settled into a groove of cranking out stilted, uncanny blogs that praise various conservative luminaries for bringing back war and rolling back woke. But the board has not limited itself to covering politics: My favorite recent Post editorial is its bizarrely strident defense of paper towels, but if you prefer the knockoff Grantland Rice ode to the majesty of football (“brutal and beautiful, precise and physical”), I won’t argue too strenuously.

Last week, the editorial board tried its hand at legal punditry in a post headlined “The Liberal Judicial ‘Resistance’ Lives.” The piece took issue with Massachusetts District Court Judge Indira Talwani’s preliminary injunction that blocked enforcement of Section 71113, a provision of Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill barring Planned Parenthood from receiving Medicaid funds. Section 71113 is the product of Republicans’ longstanding obsession with “defunding” Planned Parenthood on the grounds that it offers abortion care, in addition to services like sexually transmitted infection testing, cancer screenings, and birth control.

(Photo by STEFANO RELLANDINI/AFP via Getty Images)

For decades, Congress has prohibited the use of federal funds from paying for abortion care except in very limited circumstances, so all Section 71113 really does is deprive millions of Planned Parenthood patients of access to vital non-abortion healthcare. But this fact did not stop Republican lawmakers from taking aim at the organization in the budget reconciliation bill. It also did not stop the Post editorial board from blasting Talwani for getting involved.

“Congress has the power of the purse and can steer Medicaid funds in accordance with its political priorities,” the board writes. “But Talwani is trying to impose elaborate legal restrictions on Congress’s ability to change its Medicaid policy.”

It will probably not surprise you to learn that Talwani’s order is considerably more nuanced than the editorial suggests. In the case, California v. Department of Health & Human Services, a coalition of Democratic attorneys general argued that under the Supreme Court’s Spending Clause jurisprudence, Section 71113 imposes unconstitutionally “vague and contradictory conditions” on the states’ receipt of federal funds. Talwani found that the states are likely to succeed on this claim, and that immediate enforcement of Section 71113 would burden states with “increased healthcare costs” and result in, among other things, “reduced contraceptive care” and “delayed treatment for certain cancers.” On December 2, Talwani thus blocked the government from enforcing this provision—not permanently, but just until these legal challenges have run their course.

Both the states’ legal arguments and Talwani’s decision, in other words, are complicated. Rather than take the time to understand them, the board decided to simplify the story to more neatly align with the policy agenda of their billionaire overlord: What opponents of Section 71113 really need to do, the board argues, is show up at their polling places, not in Talwani’s courtroom. “If the policy is harmful, residents of affected states can elect senators to reverse it,” the board writes. “Judicial policymaking distorts the political process.”

You do not have to have a law degree to understand, as a practical matter, how vapid and hollow this reasoning is. Scenarios like this are exactly why judges like Talwani issue preliminary injunctions: to preserve the status quo during litigation, so that no one suffers “irreparable harm” due to temporary implementation of a probably unconstitutional change in the law. An eventual court determination that Section 71113 is indeed unlawful would be of little use to Medicaid patients who die in the meantime because their doctor went out of business.

The board evidently does not know how any of this works, or why it is important. Instead, it urges people affected by Section 71113 to simply wait for two or four or six years until the next time they have the opportunity to cast a ballot to maybe, possibly, hopefully flip one of 100 seats in the U.S. Senate. “Don’t sue, vote” is the sort of condescending prescription that sounds reasonable only if you are a handsomely compensated opinion writer who has never in your life spent a moment worrying about whether you can get a doctor’s appointment, and, at least until Bezos finally replaces you with an AI simulacrum of yourself, you never will.

(Photo by BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

It is of course true, as the board writes, that under Article I of the Constitution, Congress “has the power of the purse.” But—and I can’t believe I have to say this—this does not mean that Congress can do whatever it wants. Exercises of the Spending Clause power are, like any exercise of any enumerated legislative or executive power, subject to the constraints of the Constitution. By this editorial’s logic, if Congress were to pass the Black People Can’t Vote Anymore Act of 2025 tomorrow, a court ruling that strikes it down under the Fifteenth Amendment would be “judicial policymaking” that “distorts the political process.”

Over the course of her 45-page order, Talwani explains in great detail why, in her view, the states are likely to prove that Section 71113 is unconstitutional. One can agree or disagree with her conclusions, but the editorial board does not even try to make an argument. Instead, it reflexively wags a finger at this “activist” judge for having the gall to tell Mister Trump what to do, and then clocks out after six half-assed paragraphs.

If Bezos, that champion of personal liberties and free markets, wants to implement an editorial strategy that results in a venerated newspaper hemorrhaging subscribers and publicly humiliating itself, that’s his prerogative. But in my view, blogs like this one call for more accountability than the current model, in which editorials represent the “views of the Post as an institution.” If the Post is going to subject readers to arguments that a thoughtful AP US History student could dispatch with ease, the Post should at least include a real byline on the editorial, so I can make fun of whomever imagined it would be smart to sign their name to it.