With a 6-3 supermajority on the Supreme Court, the conservative justices have jumped feet-first into their favorite culture wars this term, taking on cases that could allow them to eviscerate the constitutional right to abortion care and empower millions of people to carry guns in public. Beyond those flashy cases, though, those same justices have been methodically teeing up another legal revolution that will entail profound consequences: the slow-motion destruction of the modern administrative state.

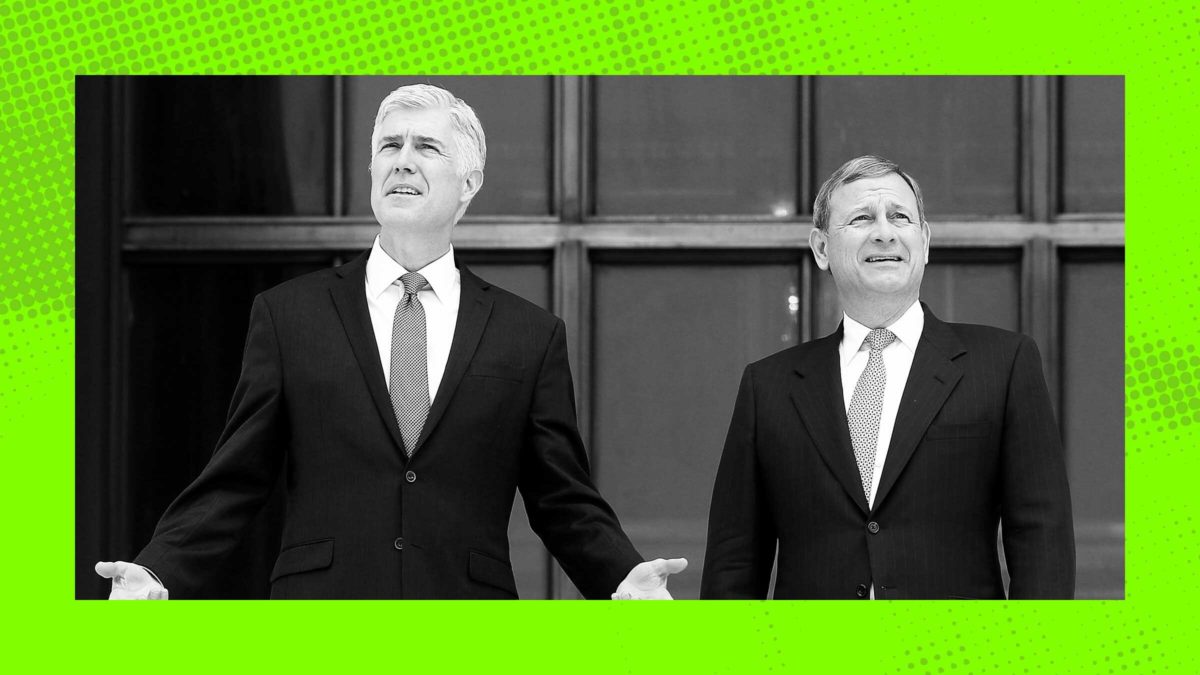

Later this term, the Court will hear oral argument in West Virginia v. EPA, a challenge to the Environmental Protection Agency’s authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions that will take place even as unchecked greenhouse gas emissions threaten to plunge the planet into a heat-induced death spiral. This has long been a pet project for the conservative legal movement’s luminaries, most notably Neil Gorsuch, and it’s going to be really, really, terrible when they succeed.

Below, we answer all your most pressing questions about how a significant amount of policymaking power currently vested in nonpartisan subject matter experts could soon be in the hands of six life-tenured reactionaries who are accountable to no one.

What is the “modern administrative state,” exactly?

The Constitution tasks Congress with the work of passing laws, but the executive branch is charged with enforcing those laws. Executive agencies like the EPA or the United States Department of Agriculture are empowered by Congress to create regulations to implement the laws Congress passes. The administrative state is sprawling, and includes both the 15 Cabinet-level agencies and hundreds of smaller agencies, too.

Why do conservative judges say they don’t like agencies?

The fancy legal justification revolves around the idea that Congress, as the democratically-elected body, should be the entity that oversees every aspect of the lawmaking process. Justice Clarence Thomas covered this at length—way too much length, including a trip back to discussing English law at the time of King Henry VIII—in a concurring opinion in a 2015 case about Amtrak. The Framers, he explained, drew sharp distinctions between the legislative and executive branches, from which America has now “deliberately departed” by “bowing to the exigencies of modern government.”

On its face, this seems relatively uncontroversial, in a sort of high school civics way. But it’s absurd and unworkable in practice, precisely because of the “exigencies of modern government.”

Why? Why not just have Congress do everything?

As you may have noticed, Congress is completely unable to get anything substantive done. Most major federal environmental laws came in a flurry in the early 1970s, but few of them have been routinely updated in the decades since. The Clean Air Act, for example, hasn’t had a major revision since 1990. Leaving the details of policymaking in lawmakers’ hands would leave us with no policy details at all.

Agencies are also nimbler than Congress. Legislation takes time, requires consensus-building, and is undertaken by non-experts. Agencies, by contrast, are largely staffed by non-political experts, avoiding the constant churn of faces on Capitol Hill that accompany each biannual rejiggering of power. The need for this sort of technical, specialized knowledge in the lawmaking process is one of those “exigencies of modern government” that the Framers could not have anticipated. An understanding of whether toxic substances are to be measured under a given statue using milligrams per liter or parts per million was not exactly on James Madison’s mind when he was writing the Federalist Papers.

Photo by George Frey/Getty Images

So when did this all start?

As with many things that make conservatives upset, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. Lifting the country out of the Great Depression required a massive infusion of government money and government oversight—hence, the increased need for agencies to oversee those processes. The New Deal era brought with it health and safety regulations and minimum wages laws, undercutting several decades of allowing companies to do whatever they wanted when it came to worker safety and pay.

Because agencies impede upon the rights of employers to do whatever they want vis-a-vis employees, conservatives view them dimly and have long pined for a return to that brand of unfettered capitalism, Justice Samuel Alito has been the most obvious cheerleader, praising on a 2018 opinion the early 20th-century era of “liberty to contract”—a euphemism for barring the government from imposing regulations on employers. It was the law of the land until 1937 when the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of federal minimum wage laws in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish.

What’s stopping conservatives from weakening the administrative state now?

Great question. The answer is two judge-made legal doctrines that govern when the federal judiciary, in theory, must defer to agencies’ interpretations of statutes: Chevron deference and Auer deference.

Chevron deference arose out of a 1984 Supreme Court case that is still important enough to have its own page on the Department of Justice’s web site. The case, Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, was about how federal courts should review an agency’s construction of a statute that Congress gave it the authority to administer. Under the standard announced in Chevron, courts have to defer to the agency’s read as long as it is reasonable and Congress did not otherwise address it. Auer applies the same concept to regulations, requiring courts to give deference to agency interpretations of their own regulations.

Conservatives, as you might guess, don’t care for either of these doctrines. But instead of working to weaken them, many conservative judges and legal scholars are fighting to throw them out altogether, using a third concept known as the non-delegation doctrine. According to them, all congressional delegations of lawmaking authority are inherently suspect—an idea that, if it were to gain more traction, would empower judges to veto almost any agency decision they don’t like. This surfaced recently when a Trump-appointed federal judge issued a nationwide injunction against the healthcare worker vaccine mandate, arguing that Congress cannot delegate this sort of complete power to an executive agency. To let an agency create a vaccine mandate, he argued, would give them the authority “to do almost anything they believe necessary.”

Which Supreme Court justices don’t like deference?

All the usual suspects. In a speech to the Federalist Society in 2016, Alito criticized the EPA’s attempts to regulate greenhouse gas emissions for, in his words, “erasing the numbers that Congress wrote” and writing in “numbers that were more to its liking.” Thomas has taken swings at Chevron and Auer in multiple cases, writing that agency deference “precludes judges from exercising that judgment, forcing them to abandon what they believe is the best reading of an ambiguous statute in favor of an agency’s construction.” Justice Gorsuch thinks judges who defer to agencies are abdicating their job responsibilities; as a judge on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, Kavanaugh complained that it encouraged aggressiveness on the part of the executive branch. (God forbid any of the big brains of the Supreme Court ever have to defer to actual scientists and policy experts.)

Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Okay, but why? Why do conservatives hate the administrative state so much?

Because regulations make it harder for the unfathomably rich people who prop up the Republican Party and the conservative movement to remain unfathomably rich. Whether they restrict where coal mining can occur or protect essential workers during the pandemic, regulations protect corporate giants from getting to do whatever they want without facing consequences.

Second, and perhaps even more importantly, weakening the administrative state shifts power to the federal judiciary. Given that conservatives control the Supreme Court and six of the federal courts of appeals, this is exactly the result they want: If agencies are no longer owed any deference, the life-tenured ideologues on those courts get to decide what the laws and regulations mean—or, perhaps, to throw out the whole concept of binding regulations altogether.

So what’s going to happen this Supreme Court term?

Probably bad things! West Virginia v. EPA, which the Court will hear this term, is about challenges to the EPA’s ability to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from power plants—a lengthy regulatory fight spanning the Obama and Trump administrations. The Obama administration’s plan set forth detailed targets for each state but was put on hold by the Supreme Court in 2016. Trump replaced it with his own plan calling for less-comprehensive changes, but again, the courts stepped in: The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals blocked that plan earlier this year.

A decision in favor of the various challengers in the four now-combined cases could gut the ability of the EPA to enforce the Clean Air Act when it comes to greenhouse gases. And the conservatives have lots of routes to get to that result: Four justices—Gorsuch, Alito, Thomas, and Kavanaugh—have already made their positions on the subject clear. Chief Justice John Roberts, who often casts himself as the conservative wing’s more moderate member, has written things like “A court should not defer to an agency until the court decides, on its own, that the agency is entitled to deference.” During Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation hearings, she refused to answer a question about climate change because, she explained, doing so would amount to “soliciting an opinion” about “a matter of public policy” rather than acknowledging that climate change is a scientific fact. None of this bodes well for people who think breathing clean air is an important goal for which government should strive.

What would this mean beyond West Virginia v. EPA?

If agencies are less able to issue binding regulations, as Thomas and company would prefer, a lot more, in theory, could be on the chopping block: workplace safety rules, food additives rules, building materials rules, and so on. More will be left to a dysfunctional, gerrymandered Congress—and, if some piece of progressive legislation that delegates power to agencies does somehow sneak through, there remains the ever-present possibility of a judicial veto. This is the future the conservative legal movement has long dreamed of. They are closer than ever to realizing it.