For the past several years, Texas Governor Greg Abbott has been engaged in a brutish game of presidential cosplay. Unsatisfied with what he views as the Biden administration’s insufficiently vicious treatment of migrants, Abbott deployed Texas state law enforcement agencies to set coils of razor wire, physically barring asylum-seekers from crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. When Border Patrol agents tried to cut through the wire to do their jobs, Abbott sued to stop them, notwithstanding the terrible human cost of his actions: On January 12, a mother and two children, ages 10 and 8, drowned while crossing a section of the Rio Grande commandeered by the Texas National Guard.

Just before Christmas, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit—one George W. Bush appointee, and two Trump appointees—sided with Abbott, entering an injunction that bars Border Patrol agents from “damaging, destroying, or otherwise interfering with” Texas’s razor-wire fence. The Biden administration, alarmed by a federal appeals court’s willingness to reward shrilly xenophobic state politicians with the power to enforce federal immigration law, appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The good news is that on Monday, the Supreme Court vacated the Fifth Circuit’s order, thus affirming that, no, judges who happen to disagree with the president’s policy agenda are not allowed to appoint a shadow president instead. The bad news is that the Court did so by the slimmest possible margin: Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined the three liberal justices, while Justices Clarence Thomas, Sam Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh would have left the Fifth Circuit’s order in place. One defection from the majority, in other words, would have subordinated the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution to a state’s sacred right to facilitate the preventable drowning deaths of children.

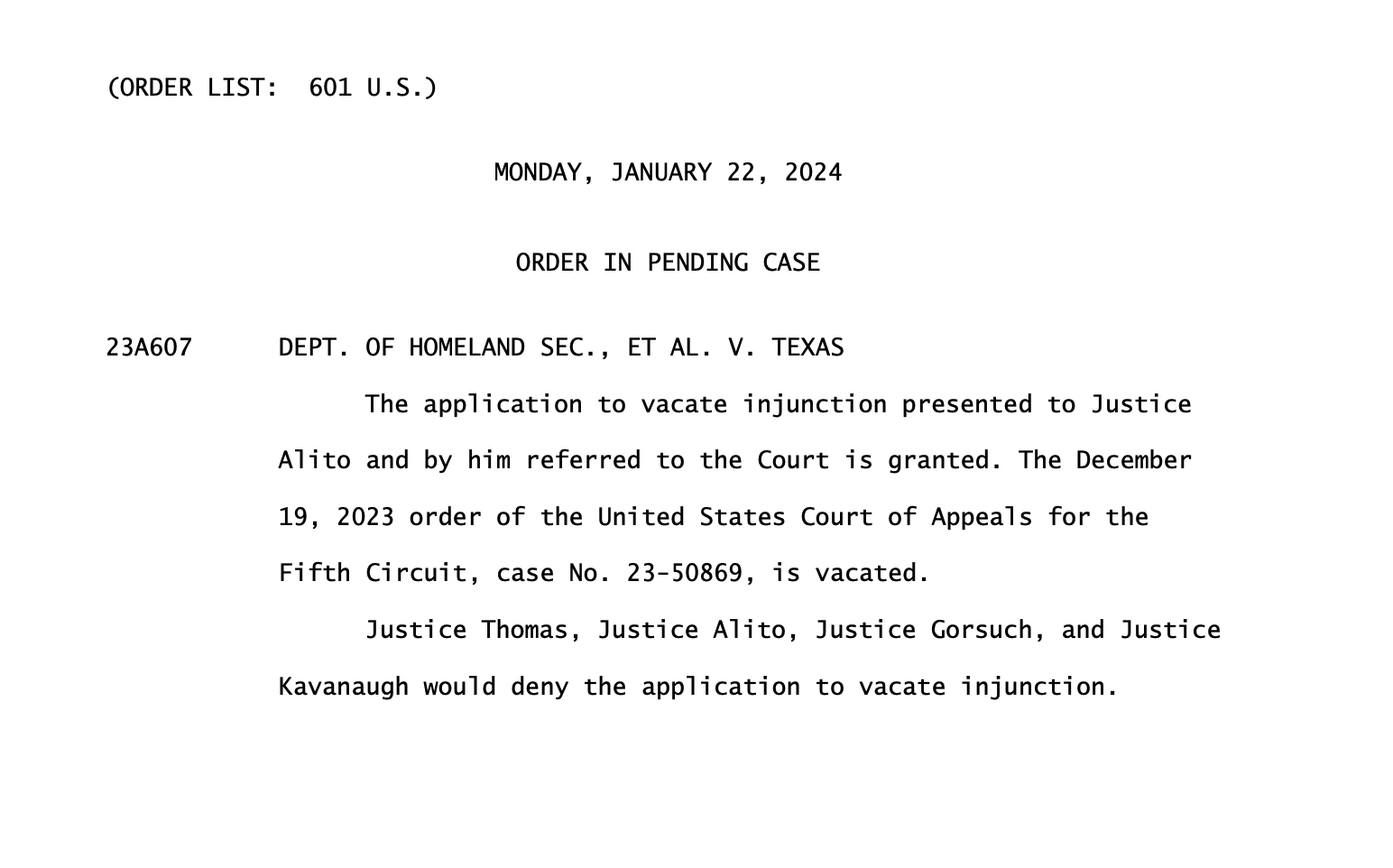

The worst news is that no one involved in this towering embarrassment—neither the five justices who blocked Texas’s state-sanctioned cruelty, nor the four justices who would have allowed it—bothered to explain themselves. Here is their order in its entirety:

It’s possible, as Law Dork’s Chris Geidner pointed out, that the result has less to do with the case’s merits than with its procedural posture. The standard for vacating an injunction pending appeal is, in theory, a difficult one for an applicant—here, the Biden administration—to meet. In other words, Kavanaugh’s vote might be less attributable to his enthusiasm for extralegal expansions of Greg Abbott’s policy portfolio than it is to his passion for evenhanded application of principles of appellate procedure.

The problem, of course, is that it’s impossible to know for sure. Although justices don’t typically write opinions explaining every vote in non-merits decisions, they’re allowed to write whenever they feel so moved, and in practice, they have no trouble getting their fingers to work whenever they’re sufficiently upset. But when they choose not to explain themselves, anyone who cares about the substance—in this case, the Supreme Court’s take on a politically-charged, life-or-death question that lower court judges will almost certainly confront again very soon—is stuck staring at these three sentences like a jurisprudential Magic Eye drawing, trying to read tea leaves that may or may not exist.

The absence of anything resembling guidance here is especially ridiculous in light of the justices’ favorite thing to complain about among friends: speculation about their motivations, especially when it comes to high-stakes decisions (like this one) issued on the Court’s shadow docket. In late 2021, for example, the Court allowed Texas’s wildly unconstitutional anti-choice bounty hunter law to take effect, functionally nullifying Roe v. Wade in America’s second largest-state. But when critics like The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer called attention to this objectively correct statement, Alito went on one of his trademark unhinged tirades, blasting the charges “false and inflammatory” in a speech at the University of Notre Dame. “We did no such thing, and we said so expressly in our order,” he said.

When someone dares suggest that you’re an anti-choice zealot (Getty Images)

The following year, when the Court stayed a lower court order that had invalidated an illegal racial gerrymander in Alabama, Kavanaugh cranked out one of his trademark superfluous concurrences, dismissing those upset by the Court’s apparent embrace of an illegal racial gerrymander as shrill rubes who simply do not understand How The Law Works. The result, he warned, did not “make or signal any change to voting rights law,” and was “not a decision on the merits.” Kavanaugh went on to hand-wave away mounting criticism of the Court’s abuses of its shadow docket as “catchy but worn-out rhetoric,” which might be the most Masked Crying Wojak a Supreme Court justice has ever been.

Neither tut-tutting lecture turned out to be accurate. A few months after the Texas decision, the Court overturned Roe on the merits docket. And although the justices eventually scrapped the Alabama map, they did so only after the 2022 midterm elections had taken place, thus helping their Republican allies win a majority in the U.S. House of Representatives. But the larger point here is that the same justices bitching about the hopeless naïveté of their critics are doing nothing to dissuade their critics from pointing out that the conservatives’ primary concern sure seems to be “promoting Republican policy preferences.” In 2022, Barrett urged anyone angry about a Court decision to “read the opinion” before passing judgment. When there is no opinion to read, she can’t blame anyone for drawing conclusions that do not cast her colleagues in the most generous possible light.

Whatever the Court’s motive here, the shoddy work product entails real-world consequences: At best, permitting this much ambiguity to linger is lazy and sloppy, and at worst, it quietly gives bad-faith actors the freedom to figure out a workaround to undermine the order. Sure enough, Texas National Guard officers are already back with more razor wire to unfurl. Is this okay with the Court? Your guess is as good as mine and/or anyone’s!

Texas National Guard soldiers are setting up more razor wire here in Eagle Pass to repel illegal crossings.

Yesterday, the Supreme Court allowed the Biden administration to remove this wire but Texas is still blocking Border Patrol from processing migrants in this area. pic.twitter.com/edptUKNobz

— Camilo Montoya-Galvez (@camiloreports) January 23, 2024

When the stakes are this high, judges should have to explain themselves. People deserve to know which parts of the Constitution mean anything anymore; by the same token, people deserve to know just how close their highest court is, exactly, to endorsing small-scale coups by majority vote. When the judges tasked with answering these questions nonetheless elect to remain silent, they are not entitled to the benefit of the doubt.