If you were crossing your fingers that President Donald Trump’s fixation on executive orders might mean he would forget about judicial nominations, welcome to the club of dashed hopes. Last week, he announced his first nominees of his second term: four district court nominees in Missouri, one to the Superior Court of Washington, D.C., and Whitney Hermandorfer to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Hermandorfer is a Federalist Society fever dream of a nominee. She works in the office of Tennessee Attorney General Jonathan Skrmetti, on projects that include trying to overturn civil rights for trans people, defending Tennessee’s near-total abortion ban, and attacking birthright citizenship. At only 37, she could serve as a judge for 40 or 50 years. She’s basically a young version of Justices Samuel Alito or Amy Coney Barrett, both of whom she clerked for on the Supreme Court. She also clerked for Justice Brett Kavanaugh when he was an appeals court judge.

Hermandorfer would replace Judge Jane Branstetter Stranch, who is one of only three appeals court judges in the country who spent most of their careers as union-side labor lawyers. The contrast between Stranch and Hermandorfer highlights what a serious mistake Senate Democrats made last November, when they made a “deal” with Republicans over President Joe Biden’s remaining judicial nominees: In return for Republicans agreeing not to block the confirmations of about a dozen district court judges, Democrats gave up the chance to even try to confirm replacements to four appeals court seats, including Stranch’s.

Once Stranch takes senior status, the number of appeals court judges who spent the bulk of their careers as union-side labor lawyers will drop back to two, the same as when Biden took office. Meanwhile, as of 2022, more than half of the more than 300 active appeals court judges had spent the majority of their careers as corporate lawyers or prosecutors. This wild asymmetry is one of the reasons federal courts are so tilted towards the interests of the wealthy and powerful, and against those of workers and other regular people. Stranch’s departure and Hermandorfer’s elevation will make this imbalance even worse.

Before President Barack Obama nominated Stranch in 2009, she spent more than 30 years at a labor law firm representing workers, unions, and pension plan participants. She specialized in representing classes of workers and their families who were fighting to keep their pensions when companies threatened not to honor them because of corporate bankruptcies or scandals.

Stranch’s background representing workers was evident in her decisions, which showed an understanding of the realities of how workplaces operate. In a case in which Black workers at a grocery distribution center experienced decades of racial harassment, Stranch alone recognized the severity of what the workers had endured. Two other Sixth Circuit judges—a former corporate lawyer and former prosecutor—upheld the trial court’s dismissal of the case on the ground that the harassment was not “severe or pervasive,” because, they said, each of the eleven plaintiffs had not shown they were aware of all incidents of harassment against their coworkers.

Stranch dissented, writing that the years of harassment—colleagues frequently referred to the plaintiffs using words like the n-word, “Buckwheat,” “boy,” and “monkey”—was clearly severe and pervasive. It “begs credulity,” she wrote, to suggest the plaintiffs were not aware of harassment directed against the others.

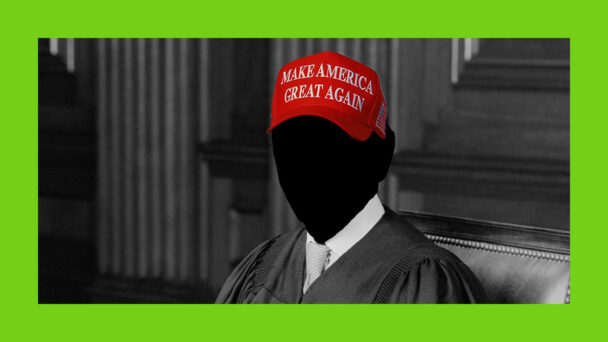

(Photo by Andrew Harnik/Getty Images)

Hermandorfer’s record could not be more different than Stranch’s, other than the fact that they both had impressive academic records. (The National Review gushed that Hermandorfer’s nomination “should put to rest the hand-wringing on the right” about Trump’s approach to picking judges, since she comes from the good grades/prestigious resume end of the far-right nominees pool, rather than the birther conspiracy theory bloggers/ghost hunters end in which Trump sometimes wades.) After clerking for fully half of the far-right supermajority on the Roberts Court, she worked for a large law firm and then took a job as the director of the Strategic Litigation Unit under Tennessee Attorney General Jonathan Skrmetti.

The same glowing National Review article described Hermandorfer as the “tip of the spear” of Skrmetti’s assault on the rights of trans people in Tennessee, including the case bearing Skrmetti’s name defending Tennessee’s ban on gender-affirming care for minors. Hermandorfer also argued against a lawsuit seeking to block Tennessee’s near-total abortion ban, and she signed a brief arguing that the Constitution’s birthright citizenship clause “rewards illegal behavior.” In case her MAGA bona fides were not clear enough, last March, she testified in her personal capacity before the House Financial Services Committee about her antipathy to federal regulation, in which she described the “bevy of aggressive and unlawful agency mandates raining down from unelected officials in Washington.”

Senate Democrats have themselves to thank for her ascension. Among the nominees they abandoned in their lame-duck “deal” with Republicans was Karla Campbell, a union-side labor and plaintiff-side employment lawyer whom Biden had nominated to replace Stranch. Another was Adeel Mangi, the Third Circuit nominee whose nomination was defeated by a ludicrous and vicious Islamophobic smear campaign.

At the time, a spokesperson for then-Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer defended the deal by saying that the appeals court nominees didn’t have the votes. But by preemptively accepting defeat, Democrats gave up on the possibility of convincing a holdout to change their mind, or confirming a nominee on a day when some Republicans were absent, as happened for other nominations the same week the deal was reached. It left multiple circuits vulnerable to “flipping” from Democratic to Republican control. As The Nation’s Elie Mystal pointed out, the Sixth Circuit’s jurisdiction includes Michigan and Ohio—states in which you would think Democrats would not want a hostile court to control election law.

As president, Biden appointed a historically diverse slate of federal judges, including many with experience as public defenders and civil rights lawyers. Unfortunately, Senate Democrats dropped the ball at key points in the confirmation process: They allowed Republicans to abuse the blue slip tradition to block nominations for dozens of district court seats, bowed to bad-faith Republican smears of some Biden nominees, and capped it off with the November “deal.” Trump’s choice to make Hermandorfer his first nominee suggests he understands the consequences of those choices. Senate Democrats didn’t.