For years, the Federalist Society has operated as the engine of the conservative legal movement: a sprawling, well-connected network that funnels conservative law students into clerkships for conservative federal judges who crank out conservative legal opinions in cases argued by conservative lawyers, all of whom look forward to catching up over drinks together at the next Federalist Society annual national convention.

Things weren’t always this way. The Federalist Society has its roots in the Reagan era, when conservative students at elite law schools concluded that they had lost the fight for the courts, and began searching for a way to return to relevance. But it took several decades of organizing campuses, credentialing academics, grooming judicial hopefuls, and waging a relentless PR campaign—not to mention untold billions of dollars in right-wing dark money—to get FedSoc to where it is today. An estimated 85 percent of the Trump White House’s appeals court nominees were affiliated with the organization, as were all three Supreme Court justices whose names appeared on a list curated by Federalist Society leadership. Compared to the next Republican presidential administration, those percentages will probably be low.

To learn more about how the Federalist Society grew from a handful of aggrieved twentysomethings to the behemoth it is today, we spoke to Amanda Hollis-Brusky, a professor of political science at Pomona College and author of Ideas With Consequences: The Federalist Society and the Conservative Counterrevolution. This Q&A, which has been edited for organization and clarity, is an extended version of our conversation with Hollis-Brusky for our four-part podcast series on the Federalist Society, which you can listen to here.

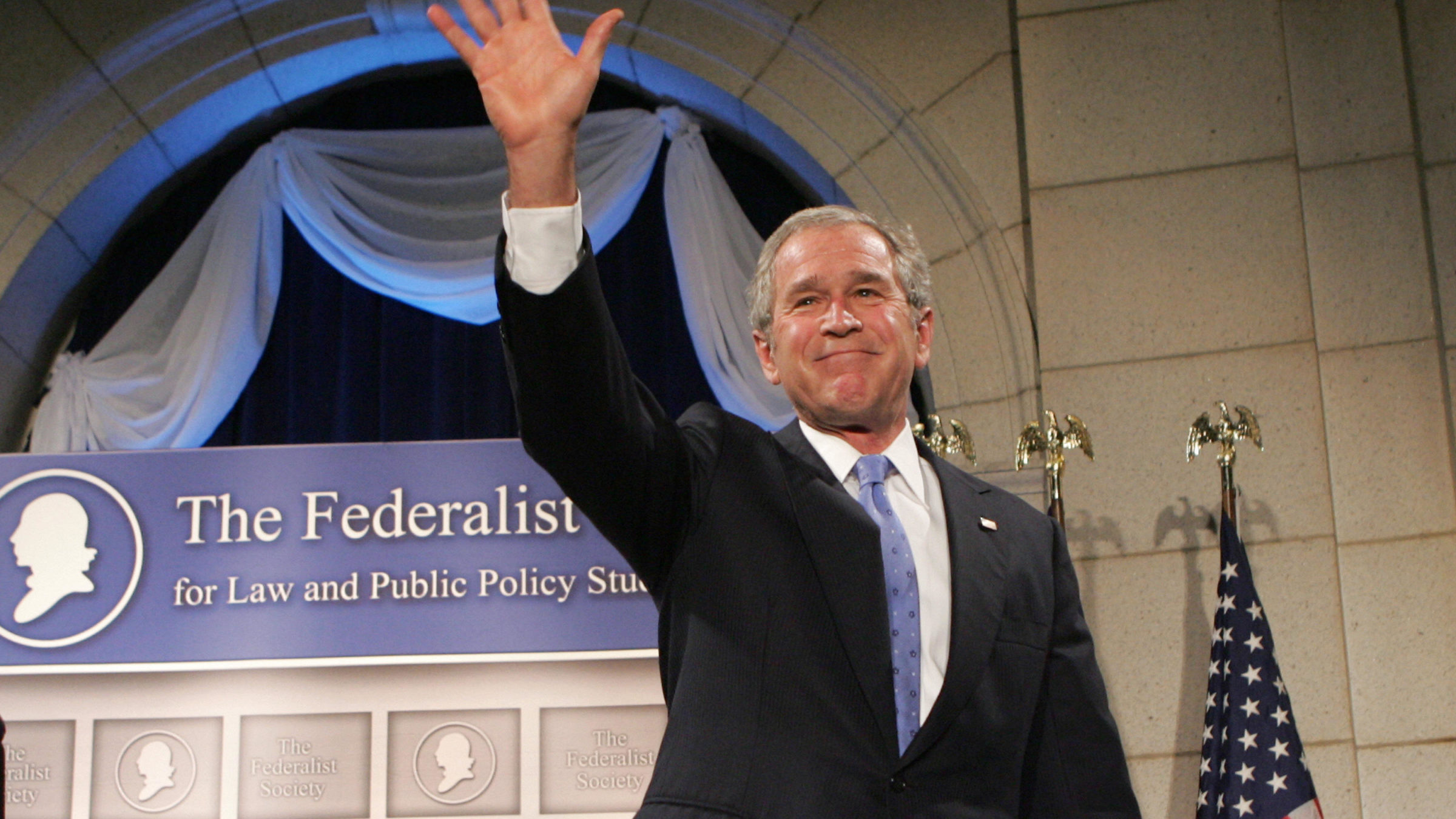

President George W. Bush addresses the Federalist Society’s annual gala, 2007 (SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images)

Peter Shamshiri: Your book talks about the idea of the judicial audience, and how the Federalist Society changed the audience that conservative judges were facing. How was the Federalist Society network involved in that shift?

Amanda Hollis-Brusky: The idea of a judicial audience, which comes from the political scientist Larry Baum, is that judges are not Vulcan-like figures. They are human beings, and human beings seek approval, particularly from people that matter to them. The Federalist Society is a wonderful example of how powerful a judicial audience can be.

Part of why the Federalist Society organized in the early 1980s is because they wanted to create an intellectual home for conservatives in law schools. But there was also this other conversation happening around conservative judges—namely, that Republican presidents would appoint good conservatives who would then, particularly if they’re on the Supreme Court, move to Washington, D.C. And because they’d want to hang out with the Georgetown set and be discussed favorably by liberal elites, some of these good conservative judges would drift to the left.

In political science, we call this judicial drift. It’s sometimes called the Greenhouse Effect, after Linda Greenhouse, the longtime Supreme Court reporter for The New York Times; the idea was these conservative judges would seek out Linda Greenhouse’s approval and start moderating their conservative principles. The Federalist Society wanted to create what its co-founder Stephen Calabresi called a counter-elite: an alternative judicial audience of conservatives and libertarians who would hold these judges accountable. They’d no longer seek Greenhouse’s approval or want to get invited to parties in Georgetown, because they’d have an entirely separate elite audience whose approval they could seek.

Peter: How did the Federalist Society help popularize originalism? In the early 1970s, originalism was essentially unheard of, but now, there’s a ton of buy-in across ideological lines—even the liberals are making originalist arguments in Supreme Court cases.

Amanda: The Federalist Society’s longest-lasting achievement might be its promotion of originalism, which it moved from a wacky off-the-wall legal theory to the dominant theory of constitutional interpretation. And the real metric, I think, of this success is the extent to which liberals on the Court and in the legal academy believe that they need to engage with originalist arguments on originalism’s terms.

The left doesn’t spend its time trying to debunk originalism. That happened at the beginning, when Justice William Brennan called originalism “arrogance cloaked as humility.” His point was that there’s no way to know the intentions of the Founding Fathers, so it’s arrogant to pretend we could. And originalism is cloaked in humility because originalists claim that they’re not drawing on their own subjective beliefs, and as Brennan said, that’s bullshit.

But the left has realized that there’s some inherent appeal with originalism—because if not the Founding Fathers’ beliefs, then whose? And that opens up the door to the critique that liberal judges who are not embracing originalism are just projecting their own values onto the Constitution. That’s the critique the left has really struggled to respond to.

Peter: It seems like a lot of the success is mostly due to the fact that the left was never really able to articulate a positive theory of their own.

Amanda: Scalia once said that when you go to the voting booth, if you don’t like Reagan, you can’t vote for Not Reagan—that you have to put up your own candidate. I do think that there’s been some effort on the left to do that. But there’s no consensus—no single theory the left has organized around, and certainly no single Supreme Court justice.

Antonin Scalia has probably done more work than anyone to legitimate originalism, and he was one of the earliest faculty advisors of the Federalist Society. Many of its founding members went on to clerk for Scalia, and took originalism beyond the law schools and integrated it into the fabric of everything. The way conservatives talked about the law, from members of Congress to law students to members of professional legal associations to members of the media—they all sort of fell in line around originalism. That’s something the left has been either unwilling or unable to do so far.

Michael Liroff, 5-4: I also think there’s a sense in the legal academy that it’s almost gauche to say, “Of course our values inform our interpretations of the law.” Everybody wants to build a society that aligns with their beliefs! And they have trouble getting very far as a result, because they are dancing around this very obvious foundation to any positive vision of the law.

Amanda: What I found to be the most compelling progressive response to originalism is a book called Keeping Faith With the Constitution, by Goodwin Liu and Pam Karlan and Chris Schroeder. They develop what they call “constitutional fidelity”—that’s a term that Reagan Attorney General Edwin Meese used to describe originalism in the 1980s, so it’s a little bit of trolling. But they say, look, what we need to use history for is to figure out the animating principles behind how certain amendments came to be. So we don’t ask, “What would someone in 1791 think the Second Amendment means?” We ask, “Why would they think they needed a Second Amendment in the first place?” What were the animating principles behind it?

We can use history to figure that out. But once we have those animating principles, they’re not static. We have to apply them to contemporary circumstances, which oftentimes means that what, for example, the Second Amendment means today is different from what it meant in 1791. But Liu and Carlin and Schroeder would say that’s a good thing. That’s how you sustain the vitality of the Constitution.

I honestly can’t tell you why that hasn’t caught on, because I think it draws on the best trappings of originalism: It grounds the meaning of the Constitution in something. But then it also is a sort of living Constitution.

Trump Attorney General Jeff Sessions addresses the Federalist Society National Lawyers Convention, 2017 (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Peter: The Second Amendment’s history is interesting because the idea of the individual right to firearms doesn’t originate within the Federalist Society. It’s a political movement for gun rights that is followed by the creation of the Federalist Society, which built a network that could feed the political demand for legal scholarship.

Amanda: Lawyers were trying to build the legal foundations of something that exists in the public consciousness already: How do we dig up the right kind of supporting evidence so that our Supreme Court justices can articulate in legal language what many in the public already believe, which is that the Second Amendment, despite how it’s written, actually protects an individual right to keep and bear arms?

So the Federalist Society was following the political and cultural movement here. But this was really important work, because you can’t articulate an argument in the law—particularly one which goes against hundreds of years of precedent—unless you can provide some kind of authoritative source that convinces people, “Hey, we got it wrong for 150 years.”

Contrast that with a subject like campaign finance. That’s a movement where the Federalist Society network is leading—they’re pushing against the bipartisan consensus that we should be able to regulate the corrosive influence of money in politics. They have to craft seemingly off-the-wall legal arguments to make that case, because the ideas just don’t jive with how most people think about the role of corporations in politics.

And that’s where lawyers have a lot of power. They have this highly technical expertise and can make rulings that have a huge impact, but aren’t digestible in the same way that Second Amendment cases are for the average American. When you couch decisions in highly technical language, it muddles things enough so that the average person can’t really figure out what’s going on.

Peter: I want to ask about the credentialing function of the Federalist Society—the résumé-building activities that the Federalist Society network engages in on a regular basis. It’s sort of designed to take any young conservative law student or aspiring academic and build the steps for them to walk up into a judgeship or into the academy as they deem fit.

Amanda: The reason the Federalist Society is so powerful is it filled a vacuum. In the late 1970s, if you were conservative at a place like Yale Law School, there were few faculty members who would reward your conservatism—who would see that as a reason to promote you. Part of building a counter-elite is building up a network, so that conservatives know that if they want to go into policy, or to clerk, or to practice at the most prestigious firms, that there are mentors who will reward them and give them the kind of experience they need to access those positions of power.

If you’re a liberal or progressive lawyer, you can tap into many different networks. But there’s no single organization that does all the organizing on the left. On the right, it’s the Federalist Society. And as they’ve grown, there’s this power of attraction—folks in law school who may not even be sure they’re conservative, but they look at what the left’s got going on and at what the Federalist Society has going on, and think, Well, maybe I’ll hedge my bets. I hear this a lot when I speak at law schools—that the Federalist Society has a sort of gravity about it. It has tons of resources. It has the best speakers. It has the best dinners. It has the best networking events. And those things attract people. So it’s built itself up and become the de facto gatekeeper for any conservative lawyer who wants to access any kind of position of power and influence.

Michael: Where do you think the Federalist Society goes from here? They’re kind of like the dog that caught the car right now. From Rahimi to the post-Dobbs abortion cases to the possibility of gutting the administrative state, they’re generating a lot of governance issues for themselves. Is that tenable?

Amanda: I think this is a really interesting conversation. The Federalist Society has captured the courts, but Leonard Leo has always done his work in a way that pushes boundaries, but not to the extent that it would delegitimize the courts entirely. Many Trump judges are ready to burn down Rome to save it, and Leo’s like, “No, no, I’m deeply invested in Rome! I’ve spent a lot of time trying to get control of Rome!” When the Supreme Court pushes too far on abortion and lower courts issue these other wacky decisions, these things run the risk of delegitimizing the institution itself, and inviting the left to think about how to reform the courts so they’re less powerful and more democratic.

Justice Samuel Alito attends the Antonin Scalia Memorial Dinner at the Federalist Society National Lawyers Convention, 2023 (Photo by Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Peter: In 2022, Leo gave a speech in which he said that Catholicism is under attack from “vile and immoral current-day barbarians, secularists and bigots” who he calls “the progressive Ku Klux Klan.” It seems he has this sense, despite the fact that he is sitting on $1.5 billion and has fundamentally changed the way American law works, that the left is ascendant.

Amanda: I think Leo has what many on the Christian right have, which is sort of a missionary zeal about what he’s doing and why he’s doing it. It’s a battle between good and evil—between forces seeking to destroy America and the pillars that support it. And I do think he will push to use the law to the greatest extent to achieve, effectively, Christian nationalism by another name.

But the courts need to be intact for that to happen. And I do see Democrats mobilizing around Supreme Court reform. There is an acknowledgement that the Court is inherently broken—that it does not not align with the United States as it looks right now, and there’s no way to get it to align, and so we need to expand the Court. We need to term-limit the justices. We need to limit the power of these unelected elite judges, and get back to democratic politics. When judges push the law in ways that are out of step with how Americans understand the Constitution, and how they understand their own rights and their own power, these judges run the risk of delegitimizing the institution itself.

I wouldn’t use the dog who caught the car as the metaphor. I think it’s Icarus flying too close to the sun. Can the Federalist Society pull back just far enough to keep control of these institutions—to keep its wax wings intact? Or is the whole thing going to melt?