The Supreme Court is very likely about to take a sledgehammer to the wall of separation between church and state. Next month, the justices will hear oral argument in Carson v. Makin, a Maine school funding case that gives the conservative majority a chance to hold, for the first time, that taxpayers must support a specifically religious activity: sectarian education. That would open the floodgates to more government funding for more religious activity—even religions that treat women, gay people, and trans people as second-class citizens.

The Court is in the midst of a radical redirection on religion, which the First Amendment addresses in two clauses: one that prohibits the government from establishing an official religion, and another that prohibits the state from interfering with the free exercise of one’s religious beliefs. Between the end of World War II and the end of the Warren Court in 1969, the Court used the Establishment Clause as a powerful force for keeping government and religion apart. Today, the Court is expansively reinterpreting the Free Exercise Clause to impose its preferred religion on people who do not want to support it.

Some of the Court’s revered landmark cases have upheld the right of Americans not to have religion forced on them. In 1948, in McCollum v. Board of Education, it ruled that a public school set-aside of classroom time for religious instruction violated the Establishment Clause; in 1962, it held in Engel v. Vitale that a non-denominational prayer at the start of the school day did, too. These decisions did not reflect hostility towards religion, but protected the freedoms of Americans of all religions and no religion by erecting, as the McCollum Court put it, “a wall between Church and State which must be kept high and impregnable.”

The conservative justices have spent their entire careers in an ideological bubble that equates the Establishment Clause’s existence to an all-out assault on the Christian right’s authority to impose its views on everyone else.

As the Court moved rightward, however, it has been far more willing to allow government and religion to intermingle, rewarding the conservative Christian coalitions whose activism fueled the rise of the modern right. Last year, in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, the Court held that Montana violated the First Amendment by barring religiously-affiliated schools from a state scholarship fund simply because of their “status” as such, without regard to whether the schools were actually teaching religion—what the Court distinguished as the funding’s “use.” Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in dissent, wrote that the decision upset the balance the Constitution strikes in its Religion Clauses and “weakens this country’s longstanding commitment to a separation of church and state beneficial to both.”

Carson v. Makin threatens to go even farther: This time, the Court is being asked to require a state to fund schools that provide expressly religious instruction. Maine operates an unusual public school system: With only 180,000 K-12 public school students, it allows parents in small districts without public secondary schools to use state money to send their kids to private schools, including religiously affiliated schools. It does not allow the money to be used, however, for tuition at schools that promote “the faith or belief system with which it is associated and/or presents the material taught through the lens of this faith.” In other words: Any church is free to set up a school in Maine and get state money to pay tuition bills, as long as it doesn’t use the money to teach children that the church’s faith is the one true way.

One of the religious schools at the center of the case, Bangor Christian School, illustrates just how religious some of these schools can be. Bangor Christian is not merely affiliated with the Bangor Baptist Church; among its educational goals are leading “each unsaved student to trust Christ as his/her personal savior and then to follow Christ as Lord of his/her life,” and developing “within each student a Christian world view and Christian philosophy of life.”

Much of what Bangor Christian considers to be religious instruction is considered by many Americans to be indoctrination in plain old bigotry. The school teaches that husbands are leaders of the household, for example, and that men are to be leaders of the church. The school also says that “any deviation from the sexual identity that God created will not be accepted.” These are not views shared by a majority of Americans; they are, however, views espoused by the right-wing groups who have spent decades investing untold sums of money in seizing control of the Supreme Court.

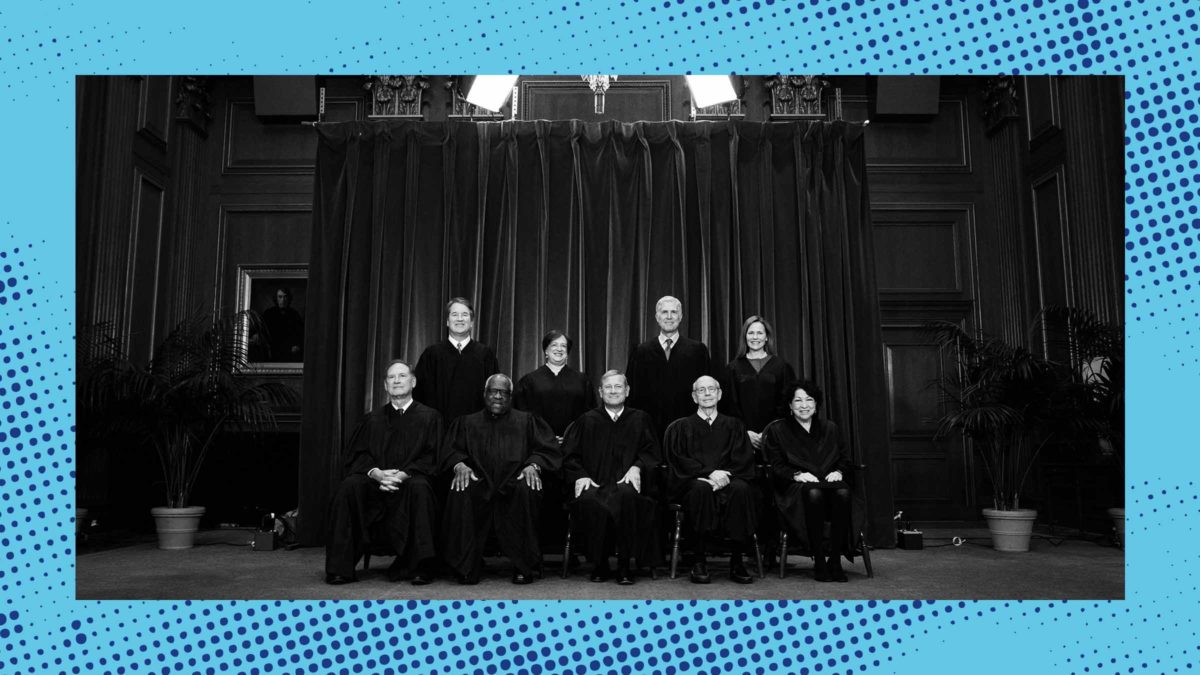

Photo by Olivier Douliery/Getty Images

David and Amy Carson, along with other parents who want Maine taxpayers to pay for this kind of fire-and-brimstone curriculum, sued. But they lost in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, which held that even if states cannot bar religious schools based on their status, states must be able to keep schools out if they are using the money to fund instruction in a particular religion, as Bangor Christian clearly is. For a Supreme Court charged with enforcing the Establishment Clause, this is a critical line to draw—or, rather, to not erase.

There is good reason, though, to believe the Court will decide that Maine’s rule is as offensive to religion as Montana’s. All five of the Court’s conservatives in 2020 voted for the parents in Espinoza, and Justice Amy Coney Barrett has since replaced Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, one of the four Espinoza dissenters. The conservative justices have spent their entire careers in an ideological bubble that equates the Establishment Clause’s existence to an all-out assault on the Christian right’s authority to impose its views on everyone else. A technical-sounding “status/use” distinction is not likely to impress them.

It is not hard for nations to fall into theocracy, as a quick global survey will confirm. But the religious right in America has always been comfortable with that model, working for decades to try to make it a reality. In Carson, the Court could finally obliterate the “no aid” principle at the heart of the separation of church and state, and require states to fund religious instruction going forward. If it does so, the floodgates will be wide open in contexts that extend well beyond schools: Before long, the government could be required to make available social welfare funds, housing funds, and so many other budget lines to organizations that specialize in religious indoctrination. Taxpayers will be forced to fund activities that tell beneficiaries of public resources that at least some of them are headed to hell.

The Court’s conservative majority appears to be prepared to hand the conservative movement a series of hot-button culture war victories: abortion, gun rights, affirmative action, and so on. There are, however, few issues the right cares about more than expanding the role of religion in American society, and using public resources to do it. Thanks to the Republican Party’s takeover of the Supreme Court, that supposedly “high and impregnable” wall between church and state might soon be reduced to rubble.