Three years ago this week, the Supreme Court made the disastrous choice to overturn Roe v. Wade, which has resulted in nearly 20 states enforcing abortion bans and countless women and pregnant people being criminally investigated, medically maimed, or even killed. A January 2024 analysis estimated that, in 14 states with near-total abortion bans, close to 65,000 rape survivors would have been unable to get abortions after the Court issued its decision. Another report estimated that the end of Roe led to $133 billion in economic losses per year, due to the costs of pregnancy and childbirth and of bans keeping women out of the workforce.

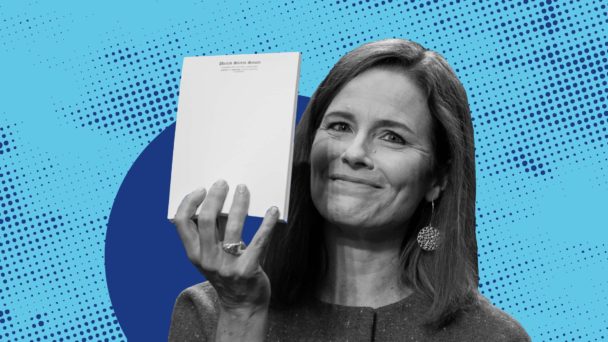

The case that overturned Roe, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, was one that the justices had no business agreeing to hear. The Mississippi abortion ban at issue in Dobbs flatly violated Roe, and every lower court judge had rejected it. But after the Court granted certiorari—and after Justice Amy Coney Barrett was confirmed in October 2020—Mississippi asked the justices to overturn the 1973 precedent. That is not how things are supposed to work, but five of them voted for that outcome. (Chief Justice John Roberts concurred only in the judgment, a result that would have gutted Roe without explicitly overturning it. It is a classic Roberts delay tactic to chip away at precedents, from abortion to voting rights, while trying to duck negative news coverage associated with rewriting the law in one step instead of two.)

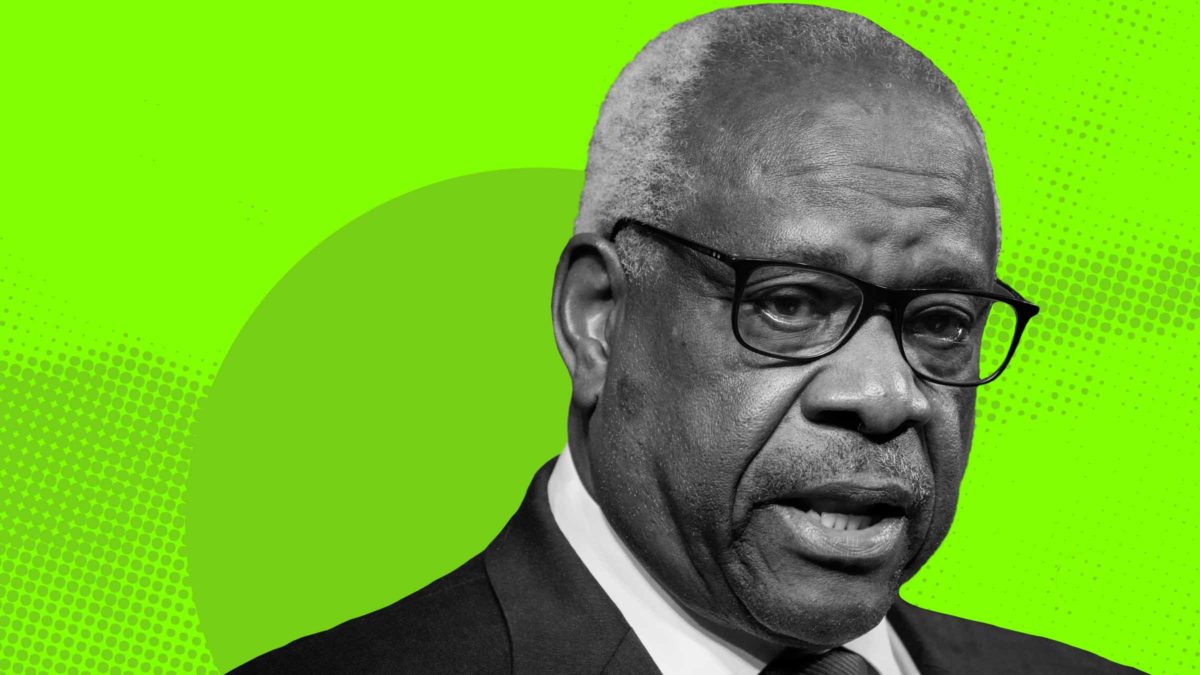

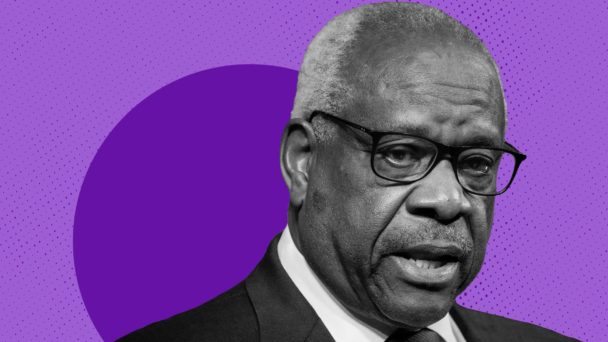

So it was galling to see Justice Clarence Thomas pen a concurrence on Friday in Stanley v. City of Sanford, a dispute about disability discrimination in retirement benefits. Thomas, joined by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, joined the bulk of the majority opinion, but had a quibble to note. “I write separately to express my concern with the increasingly common practice of litigants urging this Court to grant certiorari to resolve one question, and then, after we do so, pivoting to an entirely different question,” Thomas said. “This case exemplifies the problem.”

As several Court-watchers have pointed out, Mississippi did this exact thing in Dobbs. In 2022, both justices were happy to ignore the issue because they wanted to overturn Roe. Now, they’re deeply concerned about injustice to the other parties in the case.

“I encourage litigants before this Court to remain focused on the questions presented in the petition for a writ of certiorari—and only those questions—after this Court grants certiorari,” Thomas said. “Redirecting us to a different legal question at the merits stage can be disruptive, inefficient, and unfair to all involved.”

Thomas allows that this has happened before, but he’s apparently only upset about it now. “Of course, Stanley is not the first litigant to resist the question presented before this Court,” Thomas continues. “I hope, however, that this Court and future parties will take seriously the obligation to adhere to the question presented.”

Thomas is at once chiding litigants for not following the rules, while implicitly admitting that the justices will look the other way if they have the votes to do what the people bending the rules ask of them. In Stanley, Thomas and Barrett voted to rule against the party that had shifted the question, and gave them a finger wag for their audacity. But in Dobbs, they joined a six-justice majority that said nothing about it.

(Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images)

To see these two justices act upset now is just a reminder of how often the Court plays politics by manipulating its own docket, whether it’s in which cases or which questions they agree to review—and,importantly, when they decided to do so.

It’s worth a recitation of what happened in Dobbs. Mississippi appealed a case involving its abortion ban to the Court in June 2020, when Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was still alive. Ginsburg died three months later, and Barrett was confirmed in late October, cementing the Court’s 6-3 conservative supermajority. The justices announced that they took up the case in May 2021, though the New York Times reported that they had voted months earlier and chose to sit on the grant. More on that in a minute.

Mississippi asked the Court to weigh in on three questions, but at first, in May 2021, the Court only accepted the first: “Whether all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are unconstitutional.” (The state’s 2020 cert petition said, “To be clear, the questions presented in this petition do not require the court to overturn Roe or Casey.”) However, in late July 2021, nine months after Ginsburg’s death, the state wrote in its merits brief that the justices should overturn both Roe and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which it called “egregiously wrong.”

The Times noted that, in at least two other instances, the Court has responded to shifts in the question presented by either dismissing a question or an entire case as improvidently granted. But in Dobbs, the Court went along with the bait-and-switch. In his concurrence, Roberts chided both Mississippi for “bluntly announc[ing]” that the Court should overturn Roe, and his colleagues who “reward[ed] that gambit.”

As for the timing of the Dobbs grant, the Times reported that the justices voted 5-4 in January 2021 to take the case, with Roberts joining the three liberals in opposition. Barrett initially voted yes, but reportedly told Justice Samuel Alito that she didn’t want them to hear the case that term as she had just joined the Court three months prior. Justice Brett Kavanaugh allegedly suggested to his colleagues that they not announce the cert grant, and keep re-listing the case for conference until there was more distance from Ginsburg’s death.

The Court announced the grant in May, but sometime before then, Barrett switched her vote to a no. But since only four votes are required to take a case, the yeses won, and Barrett ultimately voted to overturn Roe. She joined Alito’s opinion in full and didn’t write a single word for herself. Now, she has the nerve to join Thomas’s concurrence in Stanley that litigants are engaging in bad behavior by switching questions.

The justices engage in other forms of trickery, like answering other questions when they have no business doing so. In the Dobbs majority opinion, Alito cited an outdated case on pregnancy discrimination called Geduldig v. Aiello, in which the Court held that state unemployment insurance laws that discriminated against pregnant women were not sex discrimination under the Equal Protection Clause. Two years after it decided Geduldig, the Court extended its reasoning to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, and the public was so furious that Congress passed the Pregnancy Discrimination Act in 1978. Yet last week, the majority in United States v. Skrmetti cited Geduldig as if it were good law. As she did in Dobbs, Barrett joined the majority opinion in Skrmetti in full.

There was chatter earlier this term about the lone female conservative being a secret moderate. Barrett’s moves in recent days should put that nonsense to rest.