Building, buying, or selling your own gun has never been easier. Go to the website for a purveyor of “weapon parts kits,” and you can anonymously order partially-completed weapons that you can fully assemble at home. Take half an hour or so to put the pieces together, and voilà, you have an unlicensed, untraceable gun. Weapon parts kits are like Lego sets that you can use to commit a school shooting.

In 1968, prompted by the fatal shootings of President John F. Kennedy, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, and the civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., Congress passed the Gun Control Act. (Imagine that: the nation’s lawmaking body passed a law to stop gun violence!) This federal statute regulates “the business of importing, manufacturing, or dealing in firearms” with familiar requirements like licensing, background checks, and serialization.

It’s because of their untraceability within this framework—no background checks, no paper trails, no nothin’—that today’s DIY-assembly weapons are commonly known as “ghost guns.” And among their explicit selling points is the ability to evade the Gun Control Act’s mandates: In marketing materials, manufacturers boast that their products are “basically a pistol in a box,” but without the “traditional headaches of background checks, registration, and serialization.” Over a six-year period beginning in 2016, the Department of Justice received over 45,000 reports of suspected ghost guns recovered by law enforcement.

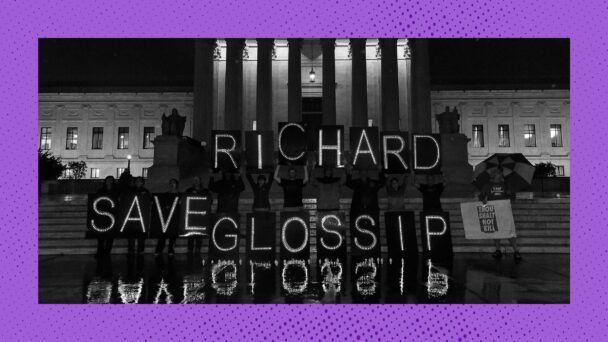

In light of these numbers, the federal government recently issued a rule making clear that laws that apply to traditional guns apply to ghost guns, too. On October 8, the Court will hear oral argument in Garland v. VanDerStok to decide whether the rule will stand, or whether people can keep amassing deadly weapons without anyone finding out.

Ghost guns recovered by the ATF in California (Photo by Robyn Beck / AFP) (Photo by ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images)

In classic lawyer-brained fashion, the main question in Garland v. VanDerStok is what a firearm is. Congress answered this question exhaustively in the Gun Control Act, which defines a firearm in relevant part as any weapon that can or is designed to “expel a projectile by the action of an explosive,” and—and this is the important part—any weapon that “may readily be converted” to do so. (The definition also includes the “frame or receiver” of any such weapon, which refers to the part that houses the gun’s internal action components).

A box full of parts that can be assembled into a fully-operational gun in about as much as time as it takes to watch an episode of The Bear seems like it would qualify as “readily convertible.” But just to make sure things were as clear as possible, the DOJ issued a rule in 2022 saying as much, specifying that “firearms” include weapon parts kits that are “designed to or may readily be completed, assembled, restored, or otherwise converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive.” The rule states that frame and receiver kits count as frames and receivers, too.

Ghost gun sellers challenged the rule as a case of a federal agency overstepping its authority. The case bears the name of Jennifer VanDerStok, a gun owner in Texas. But her co-respondents include Tactical Machining, a weapons retailer, and the Firearms Policy Coalition, a gun advocacy organization to which VanDerStok belongs; several other weapons manufacturers, sellers, and activists joined the suit after it was filed. A panel of three Trump-appointed judges on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals bought VanDerStok’s argument that the Gun Control Act does not cover weapon parts kits, concluding that the rule “flouts clear statutory text and exceeds the legislatively-imposed limits on agency authority in the name of public policy.” The Supreme Court will now hear the DOJ’s appeal.

The implications of this case will be clear to anyone with a passing familiarity with America’s gun violence crisis: Preventing the DOJ from closing the ghost gun loophole will likely get people killed. In its briefing, the government warns that if the Supreme Court affirms the Fifth Circuit’s ruling, anyone from a bored teenager to someone with a long history of violence can walk into a 7-Eleven, buy a prepaid debit card, and anonymously buy a ghost gun kit online. An amicus brief filed by Frank Blackwell and Bryan Muehlberger, the parents of victims of a 2019 school shooting, recounts how a teenager who could not legally buy a gun was nonetheless able to use an untraceable ghost gun to kill their children, Dominic Blackwell and Gracie Anne Muehlberger. “Frank and Bryan never want another family to experience their devastating loss of their children,” they write. “And for that reason, they implore the Court to reverse.”

Garland v. VanDerStok bears a strong resemblance to Garland v. Cargill, the June 2024 decision in which the Court struck down a rule regulating bump stocks, which allow semi-automatic weapons to function like machine guns. There, too, an agency tasked with administering gun safety laws tried to make sure something that looks, walks, and talks like a duck isn’t treated any differently from a duck. Here, too, an agency is trying to make sure ghost guns aren’t treated differently than other guns. And here, too, another critical public safety regulation may be vulnerable to an activist Supreme Court.