In October 2016, John Kalu had finished eating and was walking back to his cell at FCI Allenwood, a medium-security federal prison in Pennsylvania, when a guard pulled him out of line for a pat-down. As Kalu alleges in his lawsuit, the guard, Middernatch, grabbed Kalu’s penis and testicles and rubbed them together with his hands. “You like that?” he asked. When Kalu said nothing, Middernatch smiled and sent him on his way.

About two weeks later, Kalu, a Black man in his 40s, was again leaving the cafeteria when Middernatch took him aside, grabbed his genitalia, and squeezed. Kalu told Middernatch he felt like he was being harassed; Middernatch responded, “You haven’t seen anything yet.”

On December 1, Middernatch made good on this promise. Again, Kalu alleges that the guard grabbed Kalu’s genitalia during a pat-down, and again asked, “You like that?” This time, when Kalu did not reply, Middernatch jammed his fingers into Kalu’s anus. “How about this?” he said.

Kalu reported the assaults to prison officials, who opened and then closed an investigation after Middernatch denied the allegations. Shortly after that, guards stripped Kalu naked and threw him in solitary confinement, where he’d eventually spend six months sleeping on a cold steel bunk without heat or winter clothing. Kalu was released from prison in 2023, but says he still experiences nightmares, and that his cellmates could hear him “cry out in distress during the night.”

In 2019, Kalu sued Middernatch, alleging that the sexual assaults he endured violated his Eighth Amendment right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment. He sought relief under Bivens, a 1971 Supreme Court case that recognized an implied remedy against federal officers who abuse their power to violate constitutional rights, even if no explicit remedy for violations exists. The basic idea is that your civil rights are meaningless if there is no way to hold violators accountable: Because, for example, the Fourth Amendment “does not in so many words provide for its enforcement by an award of money damages,” Bivens allows courts to use their powers to “make good the wrong done,” as Justice William Brennan wrote for the majority.

The justices in Bivens thought they were closing a loophole. But after Presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan appointed more conservative justices to the Court, the Court began opening up that loophole, requiring would-be plaintiffs to prove the existence of “special factors” that would justify extending Bivens to “new contexts.” If, in the estimation of an increasingly conservative Court, the proffered special factors are not special enough, the justices would conclude that the plaintiff is shit out of luck.

Sure enough, a federal trial court dismissed Kalu’s case, and earlier this month, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit affirmed. The legal system’s collective response to the violence and abuse Kalu endured during his incarceration is a halfhearted shrug, along with a formal declaration that his constitutional rights are indeed, for all intents and purposes, meaningless.

Justice William Brennan, 1986 (Photo by Janet Fries/Getty Images)

The movement to gut Bivens culminated in two recent Supreme Court cases, Hernandez v. Mesa and Egbert v. Boule, both of which are cited throughout the Third Circuit’s Kalu opinion. In Hernandez, decided in 2020, a five-justice majority declined to allow the family of 15-year-old Sergio Adrián Hernández Güereca to sue Jesus Mesa, a Border Patrol agent who shot Sergio to death in June 2010 while he was playing a game with his friends. Why? Sergio happened to be standing on Mexico’s side of the border when Mesa shot him, and this bit of international intrigue, according to Justice Samuel Alito, made Mesa’s actions “meaningfully different” than, I guess, run-of-the-mill Border Patrol shootings that occur entirely on U.S. soil. Had Sergio been standing a few feet to the north, his case might have gone forward; because he wasn’t, his family was powerless to hold Mesa accountable for killing a teenager in cold blood.

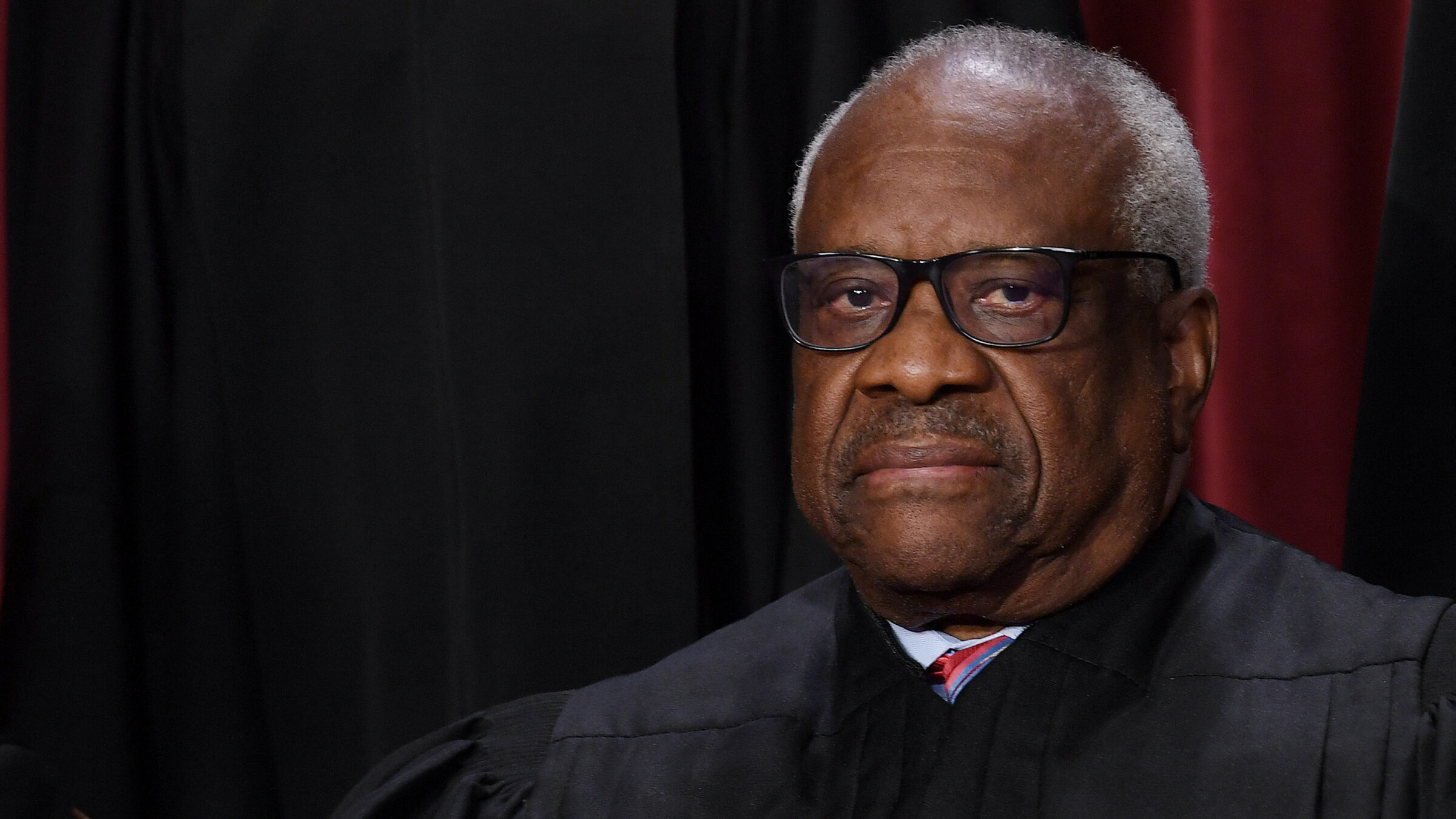

Two years later, the Court went even further in Egbert v. Boule, ordering lower courts to dismiss Bivens lawsuits if they can imagine “any rational reason (even one)” to conclude that Congress, not the federal judiciary, should be in charge of supplying legal solutions for a given problem. In his opinion for the Court, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that if today’s justices had decided Bivens, the Bivens remedy would never have existed at all. Although it did not technically overrule Bivens, Egbert makes clear that federal courts’ primary task is not protecting the rights of victims of abuse, but is instead finding reasons to let abusers off the hook—a result that, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in a partial dissent, “strip[s] many more individuals who suffer injuries at the hands of other federal officers…of an important remedy.”

Together, Hernadez and Boule are all the Third Circuit needs to shove Kalu’s lawsuit in the trash. Writing for the panel, Scirica notes the Court’s “recent and repeated warnings that we must exercise ‘caution’ before implying a damages remedy under the Constitution,” and concludes that Kalu’s case is too dissimilar from Carlson v. Green, one of the few cases in which the Court allowed a Bivens claim to go forward. Carlson was about the constitutional rights of a federal prisoner deprived of essential medical care, not a federal prisoner subjected to repeated sexual assaults, and for the Third Circuit, this distinction is enough to lock Kalu out of the courtroom. “Under the Supreme Court’s precedent, even a modest extension is still an extension,” Scirica writes. “While the official action in both cases caused harm to the prisoners, the ‘mechanism of injury’ and the nature of the official misconduct is sufficiently different.”

Previously, the Third Circuit has allowed Bivens cases to go forward against prison officials who failed to protect prisoners from sexual violence perpetrated by other prisoners. But the panel has an excuse ready for this, too: The fact that Kalu alleges sexual violence perpetrated by prison guards, Scirica says, makes his case fundamentally different from those older Third Circuit cases. Although this distinction “may appear to some to be a minor one,” he says, it “furnishes a basis to hold that Kalu’s case seeks to extend” Bivens in a way that Clarence Thomas’s “any rational reason (even one)” test prohibits.

In other words, if Middernatch had harmed Kalu by denying him a medically necessary blood transfusion, perhaps Carlson would allow Kalu to sue him in federal court. Or if Middernatch had harmed Kalu by looking the other way while his cellmate sexually assaulted him, perhaps Third Circuit precedent would allow Kalu to make his case before a jury. But because the allegations of harm to Kalu took the form of sexual assaults, not the deprivation of medical care—and because Middernatch committed the alleged sexual assaults himself—the panel throws up its hands and declares the legal system powerless to force Middernatch to face consequences for his actions.

(Photo by OLIVIER DOULIERY/AFP via Getty Images)

Conservatives who criticize Bivens typically cast it as the product of judicial activism, which in practice functioned as a catch-all term for Warren-era Supreme Court decisions they did not like. “In all but the most unusual circumstances, prescribing a cause of action is a job for Congress, not the courts,” Thomas wrote in Egbert; unelected judges, he continued, should not “second-guess” lawmakers’ decisions, even when the bills they pass “do not provide complete relief.” Sure enough, in Kalu, Scirica notes that Congress has passed legislation that relates to prison litigation and sexual assault in prisons, but did not include options for victims to bring lawsuits against individual officials. Such a “pattern of congressional inaction,” Scirica says, quoting Hernandez, “gives us further reason to hesitate about extending Bivens in this case.”

Like most paeans to abstract separation-of-powers principles, this argument ignores the reality that Congress is quite bad at its job, on the rare occasions that a body as sloppy and scattered and polarized as Congress is capable of doing its job in the first place. It also glosses over the fact that for a person incarcerated in federal prison, “Write a letter to your member of Congress and ask them to propose amendments to the Prison Rape Elimination Act” is not a meaningful solution to the problem of a prison guard stalking them outside the cafeteria.

Hernandez and Egbert and Kalu are not noble exercises in judicial restraint. They are policy choices about when it is acceptable for the legal system to leave victims of abuse without recourse, and when to allow perpetrators of that abuse to keep violating civil rights with impunity.

In a separate opinion in Kalu, Judge L. Felipe Restrepo highlights the real-world implications of such choices by detailing the federal government’s “alarming” failures to keep people in its custody safe. A recent Department of Justice investigation, for example, found that the Bureau of Prisons does not rely on the testimony of incarcerated people to discipline BOP employees unless other evidence “independently establishes the misconduct,” which means that if an assault isn’t caught on video or established by “clear forensic evidence,” an employee who denies allegations against them effectively wins by default. At the same time, if a BOP employee admits to sexual conduct during an internal investigation, that admission cannot be used against them by any law enforcement agency. As Restrepo observes, this means that BOP employees “who admit to crimes are effectively immunized from criminal prosecution,” as long as they are savvy enough to confess in the right forum.

Against this backdrop, calling the existing statutory scheme “incomplete” is, if anything, a gross understatement. But, Restrepo continued, the justices have spent decades making clear that these details are, legally speaking, irrelevant. “Bound as we are by the Supreme Court’s unwillingness to expand to any new context, I reluctantly concur in the judgment,” he concludes.

Judges are fond of casting themselves as principled, courageous defenders of the rights of people who lack political power. Bivens, in theory, could function as a backstop for those whose interests tend to slip through the cracks during the policymaking process—not only incarcerated people, but also poor people, and undocumented people, and unarmed Mexican teenagers shot to death by trigger-happy Border Patrol agents, and so on. Instead, conservative judges have assembled an arsenal of weapons for clearing their dockets of such claims as expeditiously as possible. The protections of the legal system are reserved for people they care about; people like John Kalu are on their own.