Earlier this week, the Supreme Court issued a two-paragraph order that allows the Trump administration to move forward with gutting some two dozen federal agencies, moving ever closer to realizing the conservative movement’s demented fever dream of making the government small enough to drown in a bathtub. The only justice who noted their dissent was Ketanji Brown Jackson, who over the course of 15 pages came as close as a Supreme Court justice will ever get to characterizing their colleagues as breathtakingly full of shit.

In her opinion, Jackson excoriated the Court’s “hubristic,” “reckless,” and “senseless” choice to “swoop in” and “casually discard” a lower court order that paused Trump’s layoffs while legal challenges proceed, and for “cavalierly concluding (in just one line)” that he has the better argument. She ticks through the “enormous real-world consequences” of releasing this “wrecking ball” on the civil service, which will leave normal people “paying the price.” And she offers a hypothesis to explain why the conservative supermajority voted as it did: The lower court’s order, Jackson wrote, was “no match for this Court’s demonstrated enthusiasm for greenlighting this President’s legally dubious actions in an emergency posture.” This translates roughly from legalese as “You guys are once again doing whatever Mister Trump asks.”

I do not mean to reduce Jackson’s opinion to its most frustrated snippets; her analysis of previous presidents’ effort to work with Congress to reorganize the executive branch, for example, neatly exposes the conservatives’ willingness to set aside “history and tradition” when it yields answers they do not like. But Jackson’s focus on the Court’s penchant for warping the law to suit Trump’s interests—sometimes using language so pointed that even the other liberals are reluctant to join her—has been the defining characteristic of her jurisprudence since Trump took office. For as long as she remains stuck in the minority, it might also be the most important part of her job: If she cannot persuade her colleagues that the Constitution does not imbue Donald Trump with an inviolate right to ignore it, she can at least use her platform to show the public that the institution is captured, broken, and not to be taken seriously.

(Photo by CHIP SOMODEVILLA/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

The Court has given Jackson plenty of opportunities to make her case. When it granted “Department of Government Efficiency” employees access to sensitive Social Security Administration data in SSA v. AFSCME, she wrote that the Court had transformed “what would be an extraordinary request for everyone else” into “nothing more than an ordinary day on the docket for this Administration.” When it allowed Trump to revoke the legal status of a half-million noncitizens in Noem v. Doe, Jackson rattled off cases in which the Court had blocked analogous assertions of executive power by President Joe Biden. “Somehow, the Court has now apparently determined that the equity balance weighs in the Government’s favor,” she wrote.

And in Trump v. CASA, when the Court stuck down a nationwide injunction that had blocked Trump’s attempt to revoke the Fourteenth Amendment’s promise of birthright citizenship, Jackson again noted the conspicuous timing of the Court’s intervention, which just so happens to benefit a Republican president attempting his most cartoonishly illegal stunt yet.

“The Court has cleared a path for the Executive to choose law-free action at this perilous moment for our Constitution—right when the Judiciary should be hunkering down to do all it can to preserve the law’s constraints.” she wrote. “I have no doubt that, if judges must allow the Executive to act unlawfully in some circumstances, as the Court concludes today, executive lawlessness will flourish.”

The other liberals have not always been on board with this sort of rhetoric. Justice Elena Kagan joined Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissenting opinion in Trump v. CASA, leaving Jackon to write only for herself. In Noem v. Doe, only Sotomayor signed on to Jackson’s dissent, and Kagan did not note her dissent at all. In the DOGE case, all three liberals noted their dissent, but only Sotomayor actually joined Jackson’s opinion. Kagan did not, and did not write a separate dissenting opinion of her own, which raises the question of what, exactly, she found so objectionable about Jackson’s argument.

Many of Jackson’s dissents have come in cases on the Court’s shadow docket, where pinning down the majority and dissenting coalitions is an annoyingly inexact science, since the truncated format does not obligate the justices to explain themselves or even reveal their votes. (Kagan’s silence in Noem, for example, does not necessarily mean she was part of the majority.) But a footnote in Stanley v. City of Sanford, a merits docket case the Court decided in June, provides further reason to believe that Sotomayor and Kagan are, at the very least, a little skittish of what their junior colleague is up to these days.

Stanley is a statutory interpretation case about the Americans With Disabilities Act, and the Court’s holding will make it harder for certain employees to sue their employers for alleged violations of the law going forward. In dissent, Jackson dropped a scathing footnote that describes the “pure textualism” at work in Justice Neil Gorsuch’s majority opinion as “a potent weapon for advancing judicial policy preferences,” and as “somehow always flexible enough to secure the majority’s desired outcome.”

These are jurisprudential fighting words, remarkable not because critiquing textualism as a lazy vehicle for reactionary politics is new, but because an honest-to-God Supreme Court justice is finally willing to do it in public. Yet Kagan did not dissent in Stanley, and although Sotomayor joined Jackson’s dissent in part, she explicitly disavowed this particular footnote. For whatever reason, both of Jackson’s fellow liberals thought carefully about what she wanted to say, and decided not to back her up.

Critics of dissents like Jackson’s typically point to the supposed perils of burning bridges: When you are someday asking a colleague to supply a crucial fifth vote, the argument goes, you do not want them to suddenly remember that one time you called them a partisan hack.

I have never found this especially persuasive, but to the extent that savvy coalition-building would have been an essential part of Jackson’s job once upon a time, it is not anymore. This conservative supermajority has never shown any interest in compromise, because it never has any need to do so; in the three years and change since she became a justice, Jackson’s only experience in high-stakes cases has been getting steamrolled in spectacular fashion. At this point, if you are a liberal justice, the only thing you accomplish by continuing to moderate your language is conveying the impression that you don’t actually care about losing all that much.

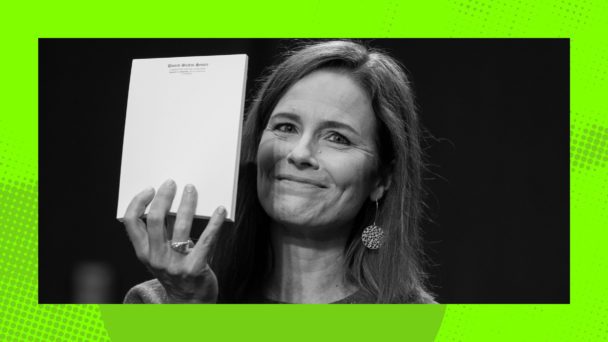

Perhaps the best evidence of the efficacy of Jackson’s approach is how angry the conservatives are with her for calling them out. Writing for the majority in CASA, Justice Amy Coney Barrett described Jackson’s argument as “difficult to pin down,” and vowed not to “dwell” on it any further.

In news that I’m sure will astonish you, conservative commentators quickly picked up on the subtext here, calling Jackson, the first Black woman justice, a “diversity hire” who doesn’t understand “what she is talking about.” But even setting aside Barrett’s hand-waving condescension, her brevity is also pretty unusual: Typically, justices relish the chance to explain in excruciating detail why their opponents are wrong, especially when they get to do so in a majority opinion. Barrett’s choice not to even try a spike-the-football rejoinder should be understood as a tacit admission that she doesn’t really have one.

(Photo by Jacquelyn Martin-Pool/Getty Images)

Only one opinion per Supreme Court case really matters: the one that earns five votes. So anytime a justice writes separately, the question is always why: Who is it for, and what does the justice hope to accomplish by voluntarily doing extra work? Some justices have reliably specific audiences: When Justice Clarence Thomas dissents (or writes a solo concurrence), he is coaching conservative activists to bring more ambitious cases in the future. Chief Justice John Roberts writes for the legal journalists whom he needs to keep writing soft-focus profiles that cast him as the Court’s principled institutionalist. Justice Brett Kavanaugh writes for his liberal neighbors in the Maryland suburbs, trying desperately to persuade them that he is neither as dumb nor as malevolent as his votes suggest.

Jackson’s audience is different: She is writing for the public. She is assuring tens of millions of people who are not lawyers that, no, they are not wrong to question the good faith of a Republican-controlled Court that keeps siding with a Republican president. She is pointing out the real-world consequences of the Court’s decisions that her conservative colleagues do not want to discuss. Most importantly, she is urging people to be skeptical of the story the Court loves to tell about itself: that the task of interpreting the law is not “political.” This has always been wrong. But no justice has come quite so close to saying it.