This term, the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority will decide whether to throw nearly 50 years of precedent out the window by functionally overruling Roe v. Wade—a result that would eliminate the constitutional right to abortion care for the foreseeable future. Sensing victory, some conservative activists are already gearing up for the next culture war: getting rid of—or at least seriously curtailing—the right to same-sex marriage.

With that, it was perhaps to be expected that the amicus briefs supporting the petitioners in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization aren’t just an anti-choice echo chamber. Several of those briefs also tee up an argument about a time-honored right-wing shibboleth: that the existence of same-sex marriage is a looming existential threat to Christians, to the country, to the very existence of Western civilization. These are tired tropes, but there’s a key difference between 2015, when the Supreme Court recognized a constitutional right to same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges, and now: This Court controlled by six Republican appointees is likely as receptive to an anti-LGBTQ message as it is to an anti-choice one.

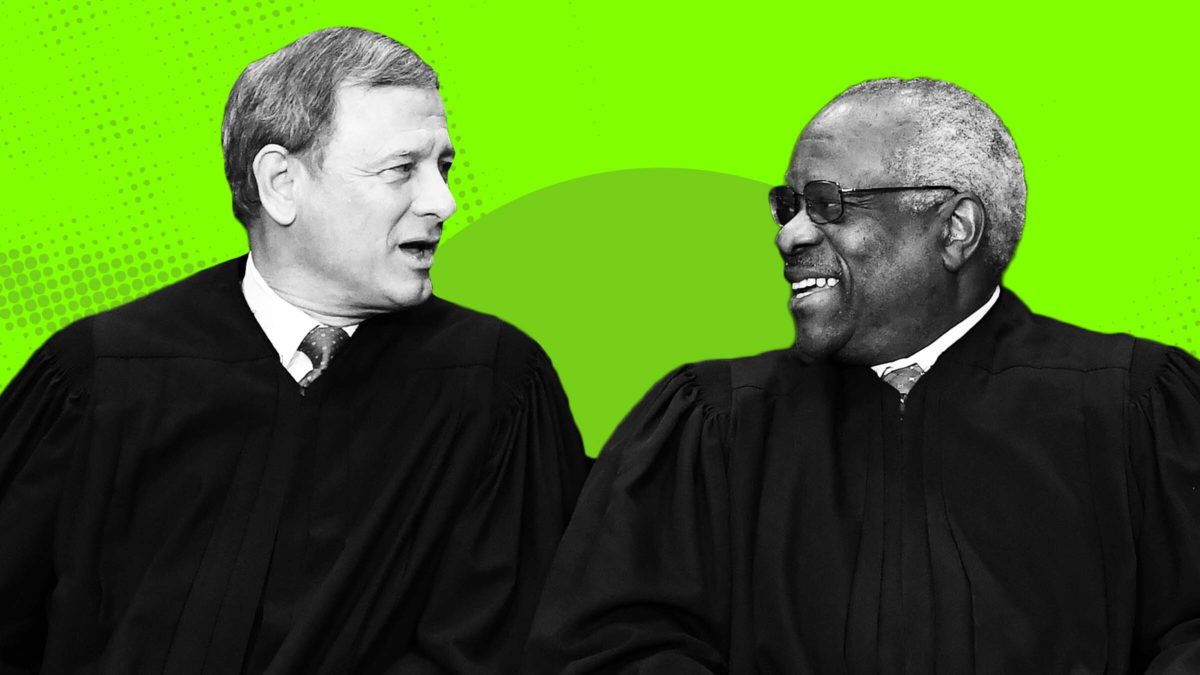

On the right, this fight has been percolating for years. Conservative groups like the Alliance Defending Freedom have raked in tens of millions of dollars, which they use to file lawsuit after lawsuit to restrict access to birth control, same-sex marriage, and transgender rights. Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, meanwhile, have made no secret of the fact they’d like to see same-sex marriage gone, complaining in Davis v. Ermold last year that Obergefell amounted to an “alteration of the Constitution” that allows “courts and governments to brand religious adherents who believe that marriage is between one man and one woman as bigots.”

Take, for example, Jonathan Mitchell. Mitchell is an attorney best known for being the architect of Texas SB8, the state’s bounty hunter abortion law. But Mitchell also harbors a deep desire to wipe out same-sex marriage, and wants the Court to get rid of both Lawrence v. Texas, the 2003 case that declared state laws that criminalize same-sex sexual intimacy unconstitutional, and Obergefell. He seems to understand that the Court is unlikely in an abortion case to overrule cases concerning the rights to same-sex intimate contact and marriage, but suggests that a sufficiently anti-abortion opinion in Dobbs could leave those decisions “hanging by a thread,” at the very least. “Lawrence and Obergefell, while far less hazardous to human life, are as lawless as Roe,” he writes.

Mitchell has a distressing amount of company. The brief of the LONANG Institute—an acronym that stands for “Laws of Nature and Nature’s God”—takes the approach of citing the losers in Obergefell, reminding the Court’s current conservatives that their predecessors have already laid the groundwork to turn those dissents into majorities. The brief cites Justice Antonin Scalia’s Obergefell grumble that that decision was “naked judicial claim to legislative—indeed, super-legislative—power.” Chief Justice John Roberts gets quoted, too, for his assertion that Obergefell “has no basis in principle or tradition.” The Thomas More Society, meanwhile, uses its brief in Dobbs—again, a dispute over a Mississippi abortion law—to complain that Obergefell “articulated no limiting principle on the basis of which States may prohibit polygamy or incestuous marriages.”

Other amici in this case launch even more ambitious attacks on the foundations of Roe. The Intercessors for America go back—way back—to invoke the Court’s finding of a right to privacy back in the birth control case, Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965, on which the right to abortion care in Roe is based. The Priests for Life note that Griswold placed birth control within the “sacred institution of marriage,” but would leave anyone who isn’t part of an institution that fails half the time to fend for themselves.

Finally, a group of conservative governors filed a brief that bemoans the passing of a bygone era when it was appropriate to have people vote on the basic civil rights of others. (Much like abortion, they’d purportedly like same-sex marriage to be regulated at the state level, not federally protected. It just so happens their states are stocked with legislators who are not fans of either.) To make their case, they lean on Chief Justice Roberts’ dissent in Obergefell, where he grumbled that “keeping the issue [of same-sex marriage] from the people is nothing more than judicial paternalism.”

The question, of course, is how amenable each of the Court’s conservatives are to arguments like these. Roberts, Alito, and Thomas are likely fully on board already. Each of them, along with Scalia, wrote dissents in Obergefell that together clocked in north of 18,000 words, most of which came down to saying that the Court’s willingness to afford same-sex couples basic civil rights constituted, as Scalia put it, “a threat to American democracy.” The unhappiness isn’t limited to Court opinions. Shortly after the 2020 presidential election, Alito got up in front of the Federalist Society and whined that people who are opposed to same-sex marriage are “labeled as bigots.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh wasn’t on the Court for Obergefell, but complained in Bostock v. Clayton County, the 2018 case that extended the protections of federal workplace antidiscrimination laws to LGBTQ Americans, that the Court was “judicially rewriting” federal law “simply because of their own policy views.” This view is predicated on a willful refusal to acknowledge political reality. Since both the House and Senate had previously voted to amend federal civil rights law to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, he reasoned, it was “therefore easy to envision a day, likely just in the next few years” when the law would change and that it was “easy to picture a massive and celebratory presidential signing ceremony in the East Room or on the South Lawn.” Judicial intervention, he argued, was thus unnecessary and premature.

Kavanaugh wrote this in June 2020, at a time when the man who put him on the bench, President Donald Trump, had spent years using his power to limit the rights of LGBTQ people generally and trans people especially. To pretend that a legislative vote on equality was just around the corner and that Trump would happily sign off on it does not exactly bespeak a robust commitment to the civil rights of LGBTQ people. Rather, it is the sort of faux-civility the Court is becoming famous for: pretending they’re independents who float far above the nastiness of partisan politics, while brutally and comprehensively rolling back the civil rights of groups they don’t like.

And what about the Court’s newest member? For three years, until she took the bench, Amy Coney Barrett was a board member at a private school that effectively wouldn’t allow children of same-sex couples to enroll, and maintained a “cultural statement” saying that “homosexual acts [are] at odds with Scripture.” In 2015, she signed a letter characterizing marriage as “founded on the indissoluble commitment of a man and a woman.” And in a 2013 law review article, she mused about “super-precedents”—according to Barrett, cases where there is “widespread public acceptance.” Notably absent from Barrett’s list? Roe, because in her view, “the public controversy about Roe has never abated.”

Take Barrett’s obvious personal comfort with bigotry where same-sex marriage and LGBTQ rights are concerned, combine it with her belief that conservative complaints prevent issues from being truly settled, and you have a recipe for someone who is exceedingly likely to be willing to overturn Obergefell.

There isn’t yet a case on the docket explicitly calling on the justices to overrule Obergefell. But the Alliance Defending Freedom is already pushing the Court to take another case, 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, from someone who is sad about the possibility they would have to interact with same-sex couples who are planning a wedding. If that sounds a lot like the Masterpiece Cakeshop case from 2018, that’s because it is—it’s even in Colorado. Especially if Dobbs goes the way of the anti-choice crowd, this is a matter of when, not if.

With Roe in mortal danger, conservatives are suddenly on the verge of being able to hollow out other civil rights they don’t care for, too. For the past six years, they’ve been stewing over Obergefell. Now, they can make their case to a conservative Supreme Court supermajority that would love to see it gone, too.