The reason the Supreme Court revoked the constitutional right to abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization is because the Court is captured by the Republican Party. Republicans have a six-justice supermajority, yielding the most conservative Court in nearly a century. And the conservatives have the votes to do whatever they want.

The Court would never say that, of course. And in Dobbs, it didn’t; instead, Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion obscured this partisan reality with loose doctrinal analysis, gesturing towards the factors judges are supposed to consider before overturning precedent like Roe v. Wade. Among them is whether a rule is “workable”—meaning, as Alito explained, if “it can be understood and applied in a consistent and predictable manner.” And according to him, Roe and Planned Parenthood v. Casey just didn’t work. Alito argued that every element of Casey, which banned abortion restrictions that created a “substantial obstacle” and imposed an “undue burden” on the right, was ambiguous. “Problems begin with the very concept of an undue burden,” he wrote, forgetting how to read all of a sudden.

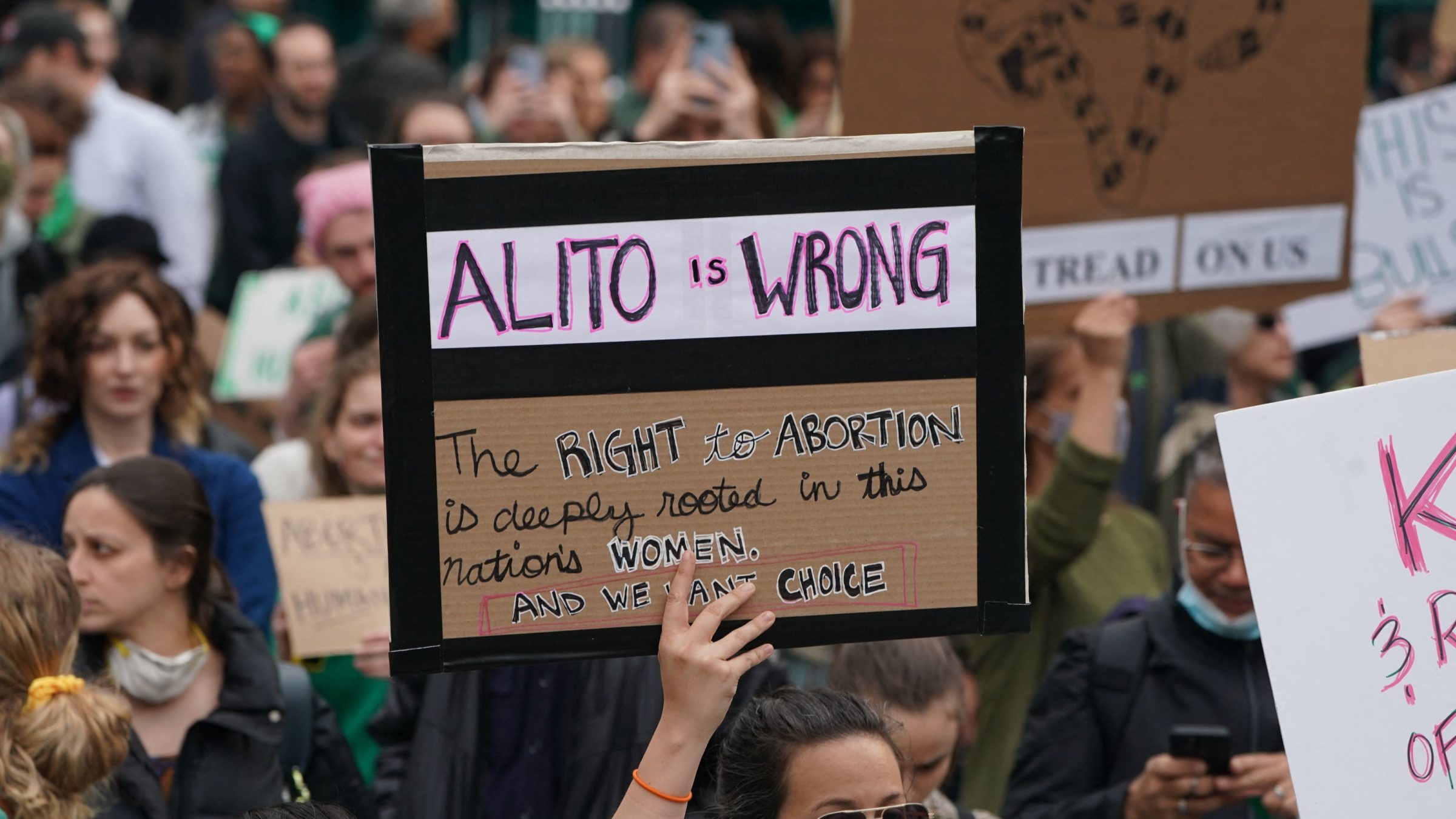

The problem with Alito’s analysis (well, one of the problems) is that the post-Roe era has not “worked,” either. Abortion-related litigation has been replete with high-profile tragedies, egregious injustices, and mass confusion. Last week, three law professors filed an amicus brief in Idaho v. United States, a case set for argument later this month, in which they lay out this argument: that Dobbs does not resemble anything that could be described as “working” and should be overruled. The opinion, they write, opened a “Pandora’s box of constitutional questions” while producing “devastating effects on reproductive health care,” and they urge the Court to “to correct its unworkable and calamitous ruling.”

Alito and company will not accept the invitation, of course, because they aren’t actually concerned about mitigating chaos so much as they are with curtailing reproductive autonomy. But the brief, written by Professors David Cohen, Greer Donley, and Rachel Rebouché, makes an explicit statement to the Court on the wrongness of Dobbs. It is a welcome reminder of how law can and should center the actual experiences of marginalized people rather than the policy agenda of the conservative legal movement.

Idaho v. United States is about the conflict between certain state anti-abortion laws and a federal law called the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA). Congress enacted EMTALA in 1985 to ensure that hospitals that receive Medicare funds provide necessary treatment to patients experiencing medical emergencies . Sometimes, doctors determine that abortion is a necessary treatment. But laws like Idaho’s criminalize the provision of care without exception for emergency medical conditions, overriding both federal law and sound medical judgment. Idaho doctors are now in a position where they’re forced to pick between their patients’ health and their personal legal jeopardy, and pregnant people struggle to access much-needed care. Some of the state’s hospitals have shut down their labor and maternity wards, and other providers have left the state entirely.

Because of Dobbs, doctors and legislators are now playing a game of chicken with women’s lives, trying to determine just how much risk—how close to death, even—a pregnant person must be before they can receive emergency care. The brief recounts one such instance in Oklahoma where hospital providers, trying to avoid legal liability, told a woman with a life-threatening pregnancy that “they could not provide an abortion until she was actively crashing in front of them or on the verge of a heart attack.” The failure of Dobbs “to avoid or mitigate even the most conscience-shocking denials of care,” the authors write, is a “telling manifestation” of its unworkability.

(Photo by BRYAN R. SMITH/AFP via Getty Images)

The brief also emphasizes that the status quo under Dobbs is inherently standardless, as the “endless complexity of pregnancy” makes many vague state-level restrictions impossible to apply to actual pregnancies, as they occur in the real world, outside the minds of anti-choice lawmakers. “Pregnancy does not create black and white realities,” the authors write: In many cases, a miscarriage cannot be clearly distinguished from an abortion. A so-called “elective” abortion cannot be clearly distinguished from a “therapeutic” abortion. A “lifesaving” abortion cannot be clearly distinguished from a “not lifesaving” abortion. Efforts to make such legal distinctions are necessarily arbitrary and, thus, dangerous to the people affected by them.

Finally, Dobbs has done nothing to address the majority’s putative concern with protecting life or maternal health, and has instead produced results that are “incoherent,” “tragic,” and “grotesquely at odds with its stated goal.” As the authors write, purported health exceptions generally do not apply until a pregnant patient has already become very sick. And exceptions for removing a dead fetus typically subject patients to cruel, medically unnecessary waits for inevitable fetal death. “Only two years after Dobbs, it is plain that the standard Dobbs adopted instead is creating far more confusion, injustice, and chaos than Roe or Casey ever did,” the professors conclude.

If it is destabilizing to give women and girls control over their lives, it must be at least as destabilizing to take that control away. This brief underscores one of the central lies of Dobbs: The Court was not trying to end chaos. It was trying to effectuate the patriarchal goals of the conservative legal movement.