For nearly all of this country’s 250-year-old history, courts deciding whether a gun law was constitutional were able to consider how much of an impact the law had on a person’s ability to exercise their Second Amendment right, and weigh that against the strength of the government’s justification for the law. If a law only imposed a small burden and for a pretty good reason? It was probably fine. If it imposed a big burden and for a bad reason? It was probably not.

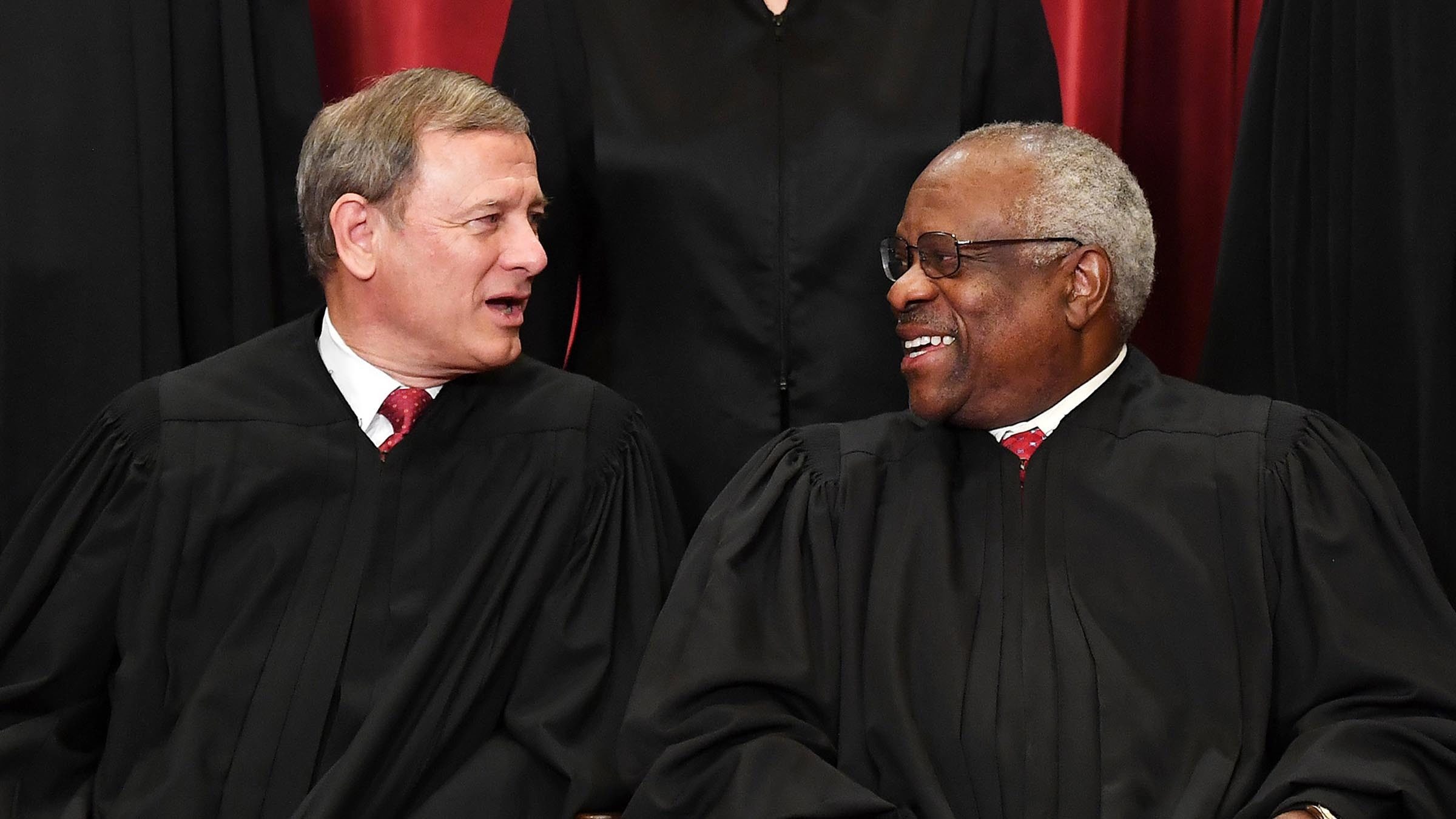

But then Republicans armed the Supreme Court with a right-wing supermajority. And in 2022, the Court’s six conservatives rejected this interest-balancing approach, adopting a new standard they presented as strict originalism. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote for the majority in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen that gun laws are presumptively unconstitutional unless the government identifies “a well-established and representative historical analogue.” Thomas also cautioned that “not all history is created equal,” and prioritized the Founding Era to the exclusion of almost all else. Suddenly, the government’s ability to enact and enforce common sense gun laws turned on Clarence Thomas’s favorite several-century-old anecdotes.

Chaos unsurprisingly ensued in the lower courts forced to apply the Supreme Court’s decision in Bruen. Perhaps most notoriously, the Fifth Circuit held in 2023 that a law temporarily disarming domestic violence offenders was unconstitutional because the government didn’t try to protect women from domestic gun abuse in the 18th century.

Pushed to attempt damage control, the Supreme Court took up an appeal in that case and issued a ruling last year in United States v. Rahimi. Chief Justice John Roberts insisted for the eight-justice majority in Rahimi that lower courts had “misunderstood the methodology” that Bruen “explained” and “clarified.” But recent appeals court decisions show that the legal landscape is still anything but clear. Lower courts trying to apply the same Supreme Court precedents are constantly interpreting them in ways that directly conflict with one another. Despite the purported guidance of Bruen and Rahimi, chaos continues to reign.

Last month, for instance, in Range v. Garland, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals held that a federal law criminalizing gun possession for people with felony convictions was unconstitutional as applied to a defendant who had been convicted of food stamp fraud. The court reasoned that Rahimi authorized disarmament temporarily and only to respond to the use of guns to threaten physical safety, which is not really a risk associated with food stamp fraud.

Around the same time, though, the Eighth Circuit also heard an as-applied challenge to the federal felon-in-possession law—this time from a man prosecuted under that law who had two prior forgery convictions. Like with food stamp fraud, any physical safety threat posed by forgery is probably limited to papercuts. But in United States v. Lindsey, the court dismissed the notion that the type of felony mattered to the regulation’s constitutionality. “Our cases rule out the need for felony-by-felony litigation,” the court wrote in a per curiam opinion.

(Photo by Matt McClain/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Appellate judges’ confusion extends beyond specific questions about whether the nature of the underlying conviction is relevant to the constitutionality of the felon-in-possession law. More broadly, judges don’t know what method they should use to evaluate any gun law in a post-Bruen and Rahimi world. Last week, in United States v. Daniels, the Fifth Circuit generally upheld the constitutionality of a law that bans drug users from possessing guns, but found the law unconstitutional as-applied to an occasional marijuana user. Writing for the three-judge panel, Judge Jerry Smith expressed sympathy for district courts since the panel was unable to “articulate a bright-line rule.” Judge Stephen Higginson also stressed in a concurring opinion that appellate courts must provide district courts with “clear, exact, and workable instructions moving forward,” and give Americans “clear notice of what conduct is criminal.”

Alas, Smith explained, Bruen and Rahimi require “a piecemeal approach.” In other words, the Fifth Circuit understands the Court’s precedents to require judges to continually resolve as-applied challenges to gun laws and determine one-by-one whether a given prosecution is constitutional. But last month, the Fourth Circuit reached the exact opposite conclusion. That court had previously ruled that there was no “need for any case-by-case inquiry about whether a felon may be barred from possessing firearms.” And in United States v. Hunt, the court said that Bruen and Rahimi “provide no basis” to reconsider its “previous rejection” of that method.

The most honest ruling may be United States v. Leiser, a Second Circuit decision from last month where the court admitted it simply had no clue what was going on. The court below found the defendant guilty of violating the felon-in-possession law, and on appeal, the relevant legal standard required the appeals court to uphold the decision unless the lower court committed “plain error.” The Second Circuit held that there could be no “plain error” because there was no settled answer to the question of whether the felon-in-possession law remained constitutional “in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decisions” in Bruen and Rahimi. “Absent such clear and binding precedent, we cannot say that the district court plainly erred,” the court concluded in a summary order.

Bruen’s demand of unthinking obedience to Founding-era mythology immediately sent judicial analysis of modern gun regulations into disarray. And Rahimi’s effort to soften Bruen’s edges has so far proven ineffective. Lower courts used to know when gun laws rested on solid constitutional ground. The Supreme Court’s harebrained endorsement of originalism turned it all to quicksand.