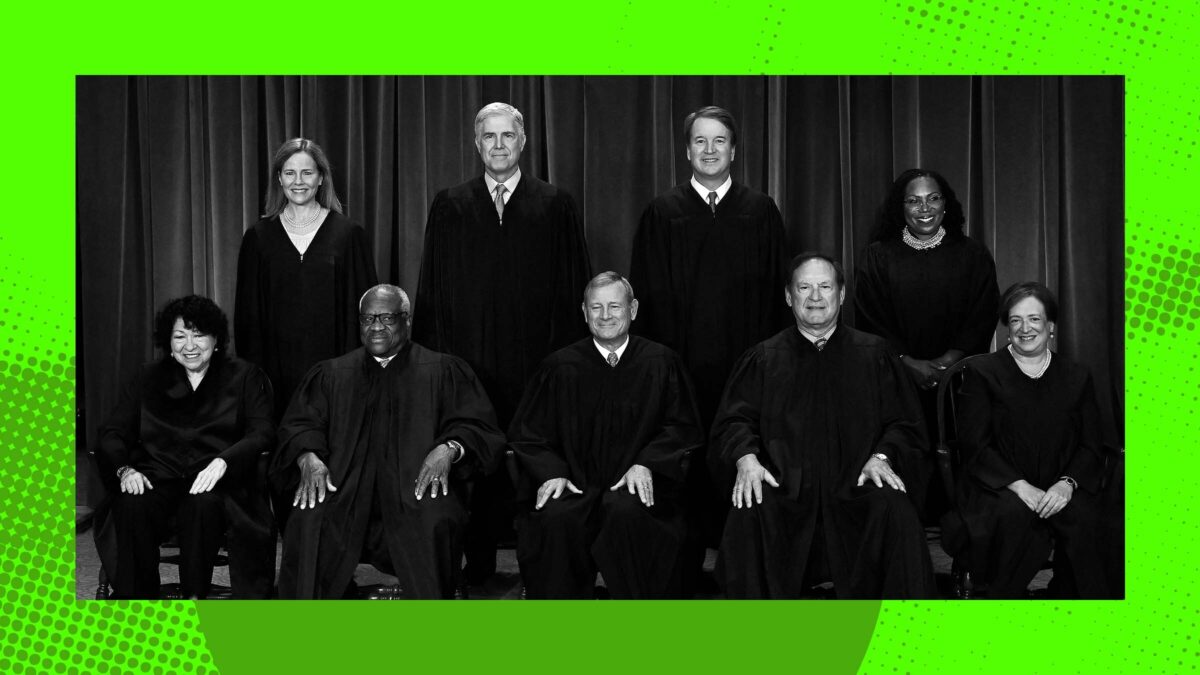

Earlier this month, the Supreme Court released its first decisions of the term that began back in October. The Court typically saves its most divisive rulings for the end of its term, in June or July, making everyone mad and then skipping town on summer vacation. The earlier cases thus tend to be those in which the justices had an easier time reaching consensus.

At first glance, the usual pattern appears to be holding. Only two of the seven decisions issued in January have any noted dissents. In the five others, all nine justices agreed on the bottom-line conclusions.

In those five unanimous cases, though, the Court strongly disagreed on how those conclusions ought to be reached. The justices repeatedly clashed over what factors the Court may consider when figuring out what a law means, from the language of the law to context clues to Founding-era history. Sometimes, as in the January decisions, multiple roads lead to the same destination. But in the more politically salient cases still to come, insisting on particular pathways would take the justices to wildly different places.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson explicitly acknowledged the conflict in Barrett v. United States, a case about whether a person could be convicted twice for a single act that violated multiple parts of a statute. Basically, “using a firearm during a robbery” and “killing someone using a firearm during a robbery” are both federal crimes with their own sentencing schemes. In Barrett, the Court needed to determine if Congress meant to authorize the possibility of two convictions for the same robbery. For the defendant, the stakes are high: the Court’s assessment of Congress’s objective would mean the difference between the defendant facing one prison term of up to 15 years, and two prison terms of up to 45 years.

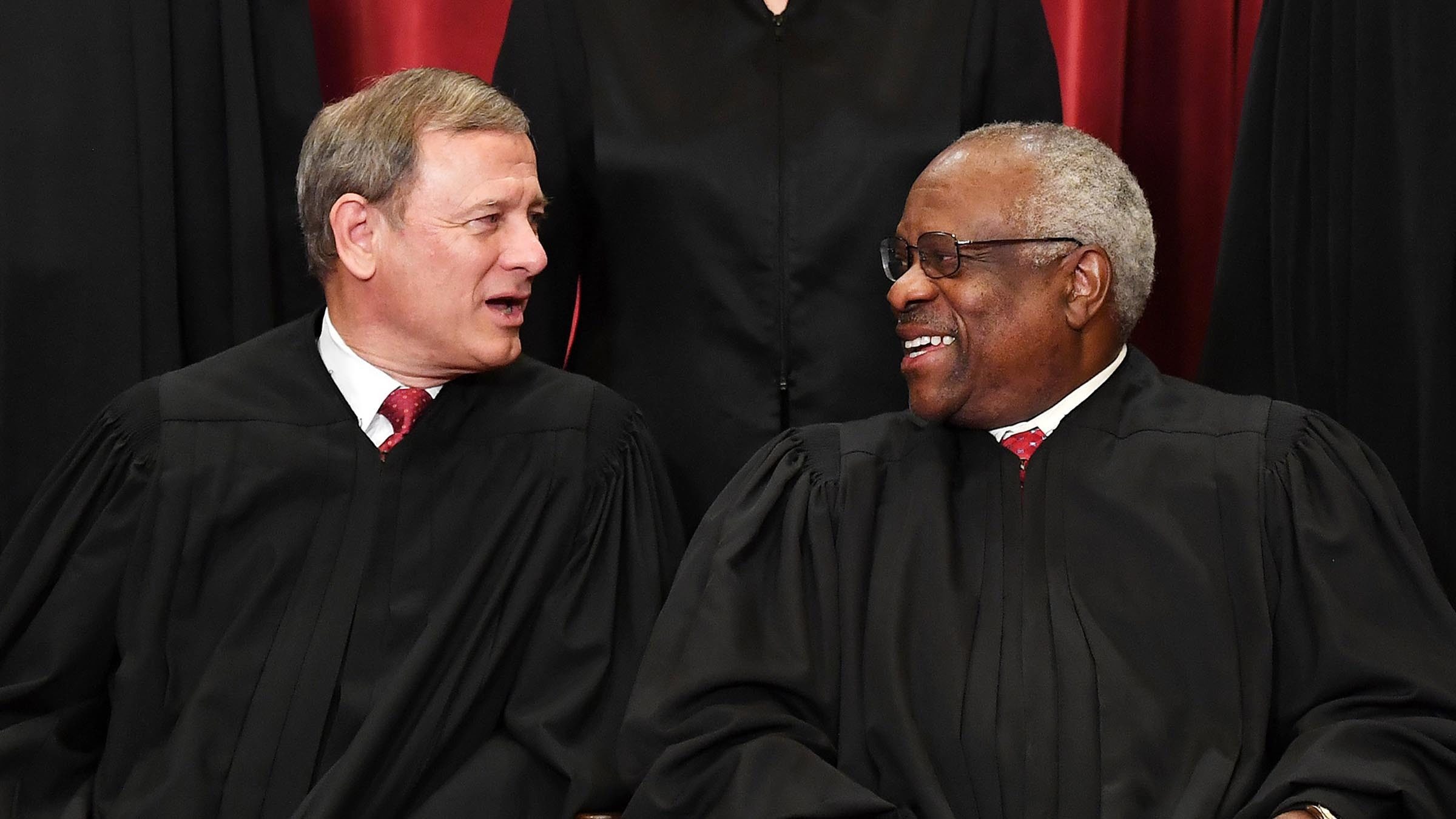

For the majority, Jackson wrote that the Court relied on “statutory text, structure, and (for those who accept its help) legislative history” to determine Congress’s intent. There’s some foreshadowing here: Even though Jackson’s opinion in Barrett was unanimous, not everyone wanted legislative history’s help. Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan joined Jackson’s opinion in full, as did Chief Justice John Roberts. The other five conservatives took the unusual step of joining everything except the three paragraphs where Jackson discussed Congress’s deliberations.

In the section the five conservatives wouldn’t join, Jackson argued that Congress doesn’t ordinarily intend to punish the same offense under two different provisions, so legislators would have probably said something if they were suddenly switching things up. “Like its silence in the statutory text, Congress’s debate-floor silence says a lot,” she said. She concluded that, in this case, it was “highly unlikely” that Congress deviated from its normal practice “without comment.” Evidently, most of the conservative justices didn’t want to legitimize drawing inferences from things members of Congress do or do not say.

(Photo by Jacquelyn Martin-Pool/Getty Images)

A methodological split popped up again in Berk v. Choy, a case about whether state laws that impose extra paperwork requirements on people filing medical malpractice suits apply in federal court. Usually, when federal courts hear state law claims, like those in medical malpractice cases, they apply the state’s substantive law but use the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Yet in Berk, a federal court dismissed a patient’s case for failure to comply with a state law requiring plaintiffs to submit an affidavit from a doctor attesting to their suit’s merit alongside their medical malpractice complaint. The Federal Rules have no such requirement.

The Supreme Court needed to decide whether the federal procedural rules displaced the state law. And to do so, wrote Justice Amy Coney Barrett for eight justices, the Court must “interpret the Federal Rules the same way we interpret federal laws more generally: by giving them their plain meaning.” Under the federal rules, a complaint just needs factual allegations that plausibly state a claim for legal relief. Because the state law requires plaintiffs to come up with more evidence, the rules are in conflict, and federal rules win. So, here, the medical malpractice plaintiff won, too.

In a solo opinion concurring only in the judgment, Jackson argued that Barrett’s interpretive method was not entirely correct. “To the extent that the Court suggests that the Federal Rule’s plain text is all that matters when answering this question, that is not what our precedents hold,” she said. Jackson highlighted previous cases where state law arguably conflicted with federal procedure. In those cases, she said, the Court explained that “Federal Rules must be interpreted not solely based on their text” but also “with sensitivity to important state interests and regulatory policies.” Therefore, Jackson said, when the Court decides cases, it “must be mindful” of what states were actually trying to accomplish—and of their own precedents.

Still another divide emerged in Ellingburg v. United States, a case involving the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act of 1996. The MVRA requires people convicted of various federal crimes to pay monetary restitution to victims. And while the defendant in this case committed his crime before the MVRA was enacted, he was sentenced afterwards, and ordered to pay thousands of dollars in restitution. He argued that this violated the Constitution’s Ex Post Facto Clause, which prohibits laws from retroactively imposing criminal punishments. The lower courts found that it did not, treating the restitution more like civil compensation, and the Supreme Court had to decide whether or not it was really a criminal punishment.

Ellingburg won. For a unanimous Court, Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote that “restitution under the MVRA is plainly criminal punishment for purposes of the Ex Post Facto Clause.” The analysis was “straightforward,” he said, because the statute explicitly described restitution as a “penalty” to be imposed at “sentencing” for the purposes of “punishment and deterrence,” and the Court recognized restitution under the MVRA as a criminal punishment in other cases, too.

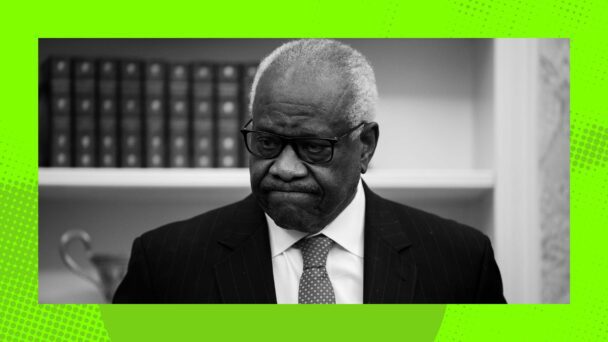

Kavanaugh reached his conclusion by pointing to the statute’s text, its structure, and the Court’s precedents. He did not, however, point to the Framers, which Justice Clarence Thomas considered an oversight. In a concurrence joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch, Thomas argued that “it does not matter what the legislature labels the law,” or for that matter, “what its stated goals were” or “which agency it vests enforcement with.”

Thomas contended that the only thing that should matter for the Court’s analysis was if the law operated in the same way as criminal laws in the 18th century. “In 1798, punishment for a crime would have been understood to refer to any coercive penalty for a public wrong,” he said. As an example, he pointed to an 1800s case where the Court regarded “nominally civil fines against a company for doing business without proper forms” as penal. Thomas reasoned that “many laws that are nominally civil today” should be subject to the Ex Post Facto Clause, too.

(Photo by Matt McClain/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

The differences in the Court’s recommended approaches are not just thought exercises with no practical consequences. Many federal laws designed to protect the public from corporate wrongdoing impose civil fines on companies that break the law. Thomas and Gorsuch’s method in Ellingburg, prioritizing history over text and context, would transform these civil fines into unconstitutional criminal punishments.

Barrett’s method in Berk, singularly focusing on the text, would further empower the Court to ignore its precedents and embrace hyper-literal readings at odds with the text’s obvious meaning. (Remember this is the Court that said laws banning gender affirming care do not discriminate on the basis of sex.)

The conservatives’ retreat from Jackson’s reasoning in Barrett, which acknowledged what lawmakers said when passing a law, would also strengthen the Court’s ability to frustrate the intent of Congress, stymieing laws they don’t like by pretending not to know what the legislators across the street were up to.

The surface-level unanimity in the Supreme Court’s recent decisions obscures a simmering dispute over the decisionmaking process, which is itself a debate over the responsibilities of the Court in a democratic society. The justices have dramatically different conceptions of who and what should matter in their reasoning. And by the end of the term, their different commitments will shatter any remaining semblance of consensus.